JULY 2016

KYIV –Nadia Savchenko had been in the air for nearly an hour when the pilot radioed to the cabin that they had reached Ukrainian airspace. She took a deep breath and then joined the others on board in celebrating her freedom with a shot of vodka. After almost two years of sobriety, the alcohol gave her a rush. She thirsted for more, but was told not to drink too much before facing journalists and delivering a statement with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. Savchenko, however, wasn't listening.

"I picked up the bottle and took as much as I wanted," she told me during an interview in Kyiv. Then she slammed down the bottle and went to smoke, taking long, deep drags on a cigarette in a small corridor at the back of the president's plane. Nobody, it seemed, wanted to be the one to stop her.

The plane soon touched down at Kyiv's Boryspil International Airport. As she was reunited with her family, Savchenko, a Ukrainian military helicopter navigator who spent nearly two years in Russian captivity, donned a white T-shirt adorned with the Ukrainian trident. Elated supporters lined up to greet her with bouquets of flowers. One of them was Yulia Tymoshenko, once a political prisoner herself, a former prime minister who famously adopted a peasant's braid to appeal to voters and now the leader of the Fatherland party on whose list Savchenko was elected to parliament. Savchenko turned away the bouquet from Tymoshenko and dodged her attempt to go in for a hug. "We aren't well enough acquainted," Savchenko told her.

Savchenko didn't want to be a part of anyone's photo op. She removed her shoes and started to walk barefoot along the runway. A mob of reporters took notice, as did the thousands watching a live stream of the event. Her bare feet and erratic behavior led many to comment on social media that she might have lost her mind in prison. Her first words were a warning for reporters: "Back up…. I'm not used to so many people being around." For Savchenko, though, there was nothing strange about removing her shoes. It was something that she had done before. "I love the feeling of the concrete under my feet, the smell of spilled jet fuel," she said.

After 708 days behind bars, many Ukrainians' hopes and prayers had been answered. Savchenko, a woman who became a symbol of Ukrainian resilience in the face of Russian aggression and whose first name means "hope" in Ukrainian, had finally come home.

Like many homecomings, Savchenko's has been bittersweet. Now under the public microscope as a parliamentary deputy, a neophyte in Ukraine's notoriously rough-and-tumble political life, Savchenko will inevitably struggle to maintain the sky-high popularity she enjoyed while a martyr in prison. And while the mostly hagiographical accounts in Ukrainian media have led the public to dub her Ukraine's Joan of Arc, after the French heroine who was burned at the stake, the reality of Savchenko is much more complex: a firebrand fraught with flaws and contradictions, uncompromising, troubled, and hard to pin down.

*

I first met Savchenko on a hot June day two weeks after her release. When Savchenko and I sat down at the RFE/RL studio in Kyiv, she apologized for being late. That morning, she had left the family apartment where she has lived since her release to begin another day of meetings with government officials and journalists. Along the way she kept having to stop to take impromptu selfies with adoring fans. "People tell me, 'My friends won't believe [I met you] if I don't have a photograph with you,'" Savchenko said, rolling her eyes.

Savchenko, who is 35, was accompanied by her younger sister, Vira, who has become a guardian of sorts, dealing with the public and the press as her sister readjusts to public life. The two women are visual opposites of each other. The daintier Vira, with spaghetti-straight dirty-blonde hair, prefers dresses with matching heels. Savchenko has an androgynous look, with cropped hair, plain trousers, and flat shoes.

Prison took a toll on Savchenko. Her voice is guttural, tainted by the rasp of a chain smoker. Her boxy frame shrank due to hunger strikes and malnourishment. Now she weighs about 70 kilograms; while in Russian captivity, her weight dropped as low as 50.

Throughout our conversation, Savchenko clasped her hands, her blue eyes focused on mine. I asked her about politics, war, and her future. Having faced dozens of TV cameras since her release, she seemed prepared with an arsenal of ready-made answers. Corruption must be stamped out. The war must end. Ukraine must hold early parliamentary elections to "infuse fresh blood" into a government that has failed public expectations and which remains dominated by oligarchs and the old guard. "There can be peace [in Ukraine] only through war," she said. "Victory doesn't have to be categorical; it can be agreeable and merciful. But we cannot surrender without a fight."

While Savchenko tempered her remarks, insisting she was for the political "middle ground," it is that volatility that has many concerned that her more militant approach and unpredictability could further destabilize Ukraine. The country is sitting on the verge of economic collapse, the war in the east is sputtering on, and political parties are splintering into new factions. The capital is rife with rumors of another revolution, something radical nationalist groups have openly spoken about for months. Some of them think Savchenko would be the perfect candidate to lead it.

Savchenko, however, said that won't happen. "I don't think I will start waving swords and [calling for people to] gather on Maidan," she said. "Not yet, at least."

*

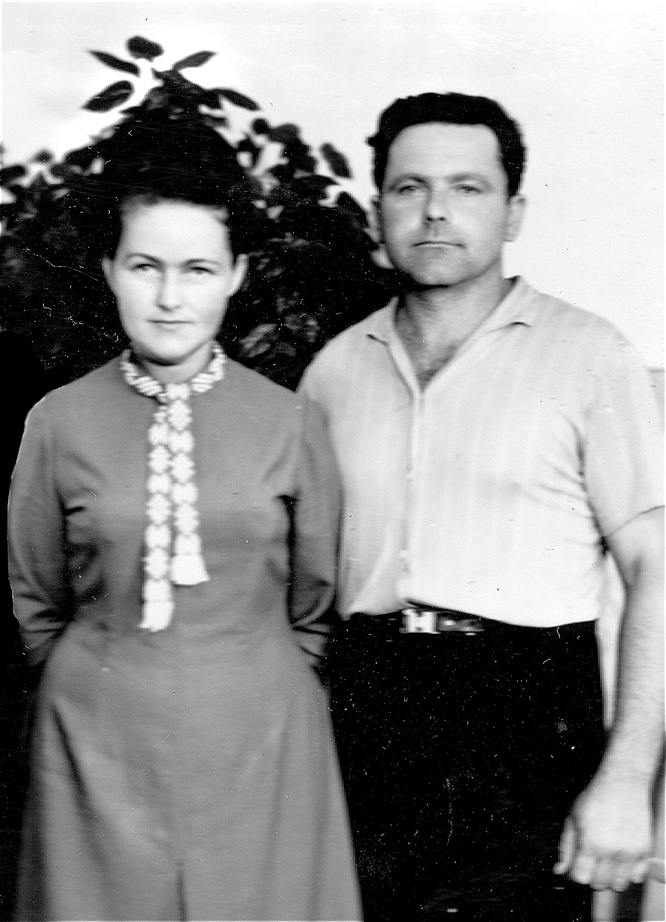

Savchenko was born into a working-class family in the then-Soviet Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, in 1981. Her father, Viktor, was an agricultural engineer and a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Her mother, Maria, was a manager at a garment factory who disagreed with her husband's politics and, as she explained to me over coffee in a Kyiv cafe, "was never baptized into communism."

Maria, a straight-talking woman in her late 70s with coarse salt-and-pepper hair, always took pride in her Ukrainian heritage, disagreed with the communist leadership, and despised the Soviet Union by the time it collapsed in 1991. She told me a story about being approached back in the day by a party official who berated her for not being a member of the Communist Party. "He asked, 'Will you join the party?' And I insisted, 'No,'" she said, then recalling how a director of the garment factory, a communist, used to steal fabric to sell it on the side for personal profit. First the director stole 40 meters of cloth, then 80 meters, she said. This went on and on for a while. When the police came to investigate after a tip-off, the director denied the charges. "He hit himself in the chest at the meeting and told them, 'I am an honest communist!'" she recalled him saying, furrowing her brow in disgust.

In 1983, Maria and Viktor welcomed a second daughter, Vira, whose name translates as "faith." They raised their family in a modest one-room, state-allocated apartment in the Troyeshchyna district, a residential neighborhood built up in the 1980s on Kyiv's northern left bank where buildings sit like Tetris pieces haphazardly dropped into place. The predominant language spoken in the home was Ukrainian, and the girls attended Ukrainian-language schools. Maria raised them to be proud patriots of their country, she said.

Their childhood was more or less a normal and happy one, Vira recalled while sipping on a fruity milkshake beside her mother in the cafe. She said that she and Savchenko behaved like typical sisters. They fought over clothes, played with dolls, and put on theater performances for their parents. "We always wanted a pet dog or cat, but mom wouldn't allow it," Vira said. "So we got pet fish. But we killed them by turning the water heater on too high in the tank."

Savchenko said she was close with both her parents. Her father, Viktor, with whom she shares a physical likeness -- square face, powerful jaw, and broad shoulders -- died in 2003. But it was her mother -- and her independent streak -- who would prove to have the biggest influence on her. "[Nadia] was always like me, like she is now [headstrong], from the moment she was born," Maria said when asked about her elder daughter. Vira nodded in agreement. "Mom's the expert," she said.

In her teenage years, Savchenko became interested in design. Skillful with her hands, she spent much of her time creating decorative objects out of paper. (That talent would stick with her, when later, inside her Russian prison cell, she would pass the time doing origami.) She also used to build model jets, a prelude to her desire to fly them. By the age of 16, Savchenko was determined to become a military pilot and fly a Sukhoi Su-24 fighter jet in the Ukrainian Air Force. She eventually joined the army, working first as a radio operator with the country's railway forces. In 2004, she joined the male-dominated 95th Airborne Brigade in Zhytomyr, where she trained to be a paratrooper.

In 2004, Savchenko got her first taste of war, when she was one of 1,690 Ukrainian soldiers sent to join the U.S.-led military campaign in Iraq. She saw her deployment as a necessary step toward becoming a jet pilot. "I believe you can only become an officer after enlisting and taking part in live combat, experiencing the smell of gunpowder," she told a Ukrainian television reporter in Iraq in 2005.

After four years in Iraq, she successfully petitioned the Defense Ministry for the right to study to be a fighter jet pilot at Ukraine's prestigious Air Force University in the eastern city of Kharkiv. She was one of the first women to be accepted there. "Many people told me to change my courses to be a helicopter pilot, because it's easier for a woman," she wrote in her memoir, published in 2015 while still in prison. "But I told them all to go to hell!" In 2009, she graduated and was soon posted to an army aviation regiment in Brody, western Ukraine.

Maria was proud of her daughter. As a young girl growing up in the Soviet Union, she, too, had dreamt of flying, but was told at the time it was impossible. "I always said that I was attracted to the sky. And if I were a boy, I would definitely become a pilot," Maria told me. "When I was a child, walking with my mother, I always asked, 'Mom, what star is that over there?' And mom would answer, 'Over there is the Great Bear, and over here is the Little Bear.'" (In Ukrainian, these are the Ursa Major and Ursa Minor constellations, or the Big Dipper and Little Dipper, respectively.) "[Nadia] realized my dream, too," Maria said.

But things quickly soured in Brody. According to Savchenko, an order came down from the Defense Ministry to not allow a woman to pilot the Su-24 fighter jet. Instead, her primary duty was to navigate the Mi-24 attack helicopter. Savchenko's frustration over having come so close to being a fighter jet pilot began to fester. She turned inward and shut others out. Then depression took over.

*

The nearly 1,000-year-old town of Brody, population 23,784, is a 500-kilometer drive west from Kyiv, and about 100 kilometers east of Lviv. Once home to a large Jewish community, today it's the site of the base for the 16th -- formerly the 3rd -- Army Aviation Brigade for which Savchenko served as a helicopter navigator between 2010 and 2014. Brody's city center, while somewhat derelict, is charming. The two-story buildings that line the main streets are a palette of faded pastels. On the first floor of the buildings are mom-and-pop shops. Above those are apartment balconies adorned with potted flowers and strung with clotheslines covered by undergarments. At its center is a square with an old wooden clock tower. At 3 p.m. on June 10, the day I visited, a man was affixing to its base a sign that read "free Wi-Fi."

Brody is a place that cherishes its heroes. Billboards outside the air base and around the city feature photographs of troops from the regiment who were killed in action in eastern Ukraine. The brigade was the first in Ukraine's armed forces to lose a soldier when the war against Russia-backed separatists broke out in April 2014.

Anna Bondarenko, the commandant of the dormitory where Savchenko lived adjacent to the brigade's base, remembered "our Nadia" fondly when asked about her. Showing me what used to be Savchenko's room, a space barely large enough for an average-sized person to lie down, Bondarenko recalled how her former resident decorated the place. It's not what one might imagine from the tough-as-nails Savchenko, who was so defiant during her trial in Russia. It's painted a muted purple with lavender and pink highlights and adorned with cartoon pictures of cats and farm animals. A tiny toy plane is affixed to one of the walls. Taped to the wall opposite is a postcard that shows a mouse grasping a string tied to a balloon which is lifting him over a cathedral and into the sky. Purple curtains dangle in front of a small northern-facing window that looks out to the drab scene of a yellow gas pipeline, a rusting fence, and a field of wild grass. Bondarenko, who said she sent a birthday card to Savchenko every year but had yet to receive a reply, has intentionally left the room vacant. "We are waiting for our Nadia to return to us," she said.

Savchenko, however, was not happy in Brody. In her memoir, she wrote about her time in the city in a chapter titled Rotten Swamp Brody. She described the city as a "nightmare" full of "gossipers." "The town locals literally pointed their fingers at me...and whispered. My [short military] haircut was strange to them! Everything about me was strange to them!" she wrote. "They would back away from me like I was some kind of devil, hiding their children from me."

Of her comrades in the brigade, Savchenko accused them in her memoir of being lazy and not taking their duties seriously. "At 8 a.m. you arrive for duty, then it's off to the classrooms (as they say, for training, but in reality it is merely to blabber and to chew [sunflower] seeds). At 9 a.m. people start to wriggle out of lessons. First it's the majors, then the captains. At noon the last lieutenant leaves," she wrote.

Brody's locals were insulted by the book's contents and many soldiers in the aviation brigade were outraged. But most of them wouldn't speak on the record when I asked about Savchenko. Some were hesitant to speak out because they said it was against the soldiers' code, while others said it was because they were afraid of possible repercussions should they criticize a national hero. "What if she becomes defense minister and I've said something [bad] about her? Then what?" one soldier said. Savchenko has already said she is ready to lead the Defense Ministry if asked.

Edward Zahurskiy, Savchenko's former commanding officer, had no problem opening up -- after getting permission from his superiors. He said Savchenko was a "problem officer" who was mentally "unstable" throughout her time in Brody. She "lacked discipline" and was "insubordinate," he said, counting on his fingers all the times she deliberately disobeyed his orders.

Another officer, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, was especially critical of Savchenko, describing her as an unhinged alcoholic who had few friends and regularly drank herself into a stupor. He remembered one instance in which she downed a bottle of booze and fell over in a patch of grass. A group of feral dogs then came over and licked her face, he said.

Savchenko herself admitted in her memoir that she had abused alcohol while in Brody. "Because of such a boring life and service in Brody, I started to ruin myself by drinking during my second year there," she wrote. Her boredom and frustration stemmed from what she described as being "reeducated" to fly the Mi-24 attack helicopter instead of the Su-24 jet.

As word spread that a journalist was around the base asking questions about Savchenko, more soldiers approached to put in their two cents. "We know who is and who isn't a hero," said one soldier. "And [Savchenko]...." He didn't finish his sentence, but just shook his head and walked away.

*

It was November 2013 and Savchenko had grown tired and annoyed in Brody, when Ukraine's Euromaidan protests began. Within days, the peaceful demonstrations devolved into violence after police forces attacked protesters in the early morning hours of November 30. Images of officers clubbing unarmed university students were splashed across television screens and newspapers, and went viral on social media. Then-Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych ordered army brigades from around the country, including Savchenko's, to Kyiv to protect him.

Watching from the barracks while on standby in Kyiv, Savchenko was shocked to her core. "Everyone understood what was going on. In our regiment everyone supported [the protesters], but only verbally, because the army -- as always -- is outside of politics," she wrote in her memoir. "But I couldn't just watch from the sidelines at everything that was happening. That's why after my combat duty I usually went to Maidan [the protests in Kyiv's capital] for the night. In the morning I returned to combat duty again."

Without permission from her commanding officer, she started leaving the regiment for longer periods of time to join the protesters on the barricades. For Savchenko, Maidan was a turning point. She fumed over what she saw as Yanukovych's abuse of the country's police and security services, which he had turned against the people.

The revolution was her first foray into political activism, but Savchenko played only a nominal role in the protests, mostly helping out with the everyday tasks of the self-defense forces -- a ragtag group of volunteers from across the country who protected the protest camp. Maria and Vira sometimes joined her, and even offered up the family's apartment to protesters who needed a shower and hot food. But Savchenko never spoke from the stage in the center of the protest camp, where the movement's leaders delivered motivational speeches. She kept a low profile.

If you search for stories about Savchenko during the protests, you won't find many. There is a video that shows her trying to dissuade young, radical demonstrators from hurling Molotov cocktails at riot police on Hrushevskoho Street – a different picture from the one painted by her critics of a bloodthirsty fascist who took up with far-right groups and wanted police officers' heads on stakes.

In late February 2014, Yanukovych fled Ukraine to Russia and the revolutionaries seized power in Kyiv. Savchenko returned to her barracks in Brody, where she watched in anger as Ukraine's military sat by as Moscow invaded and annexed the Crimean Peninsula almost without firing a single shot. The next chapter in Ukraine's crisis had begun. Savchenko was livid. She wanted to fight.

*

In April 2014, war flared in eastern Ukraine's Donetsk and Luhansk regions, a territory known as Donbas. Ukraine's underfunded, underequipped, and inexperienced military was struggling to combat a sophisticated Russia-backed separatist insurgency that spilled over from Crimea. One by one, highways, government buildings, and entire towns were being captured by the enemy. To support the troops and help stem the insurgent tide, volunteer militias were formed and sent to the front lines. Backed by wealthy oligarchs, some received newer, better equipment than the military. Many militia fighters were veterans who had combat experience from fighting in the Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s. Some had served in the army and with the Ukrainian peacekeeping mission in Iraq. A lot of them were self-defense guys from the Maidan.

Angry over her unit not being deployed to Donbas, Savchenko again defied orders and left Brody, joining the fight at the front. "I didn't think about where exactly I was going. But I knew for sure that I know how to be at war, and that my experience would be useful," she told me. Once there, she met with some of her old comrades from the Maidan self-defense forces who had teamed up with the Aidar Battalion -- one of several volunteer militia groups formed at the start of the war. "The boys said, 'Join us!' So I stayed," she said.

Savchenko's military experience was her chief asset, and the militia recognized this. They utilized her knowledge of fighting tactics and battlefield medicine. But her bluntness and unorthodox methods rubbed some fighters the wrong way. Two Aidar fighters who asked to remain anonymous -- one because he is foreign and was worried that speaking out could lead to his deportation, and the other over fears that he could be publicly persecuted for criticizing a national hero -- told me they didn't like Savchenko's cockiness, while others, they said, simply didn't like the idea of taking orders from a woman. The foreign fighter who said he fought alongside Savchenko went on a profanity-laced tirade when I asked about her battlefield prowess. According to him, she drank heavily before skirmishes, never listened to commands and would often split off from the group to fight on her own. "She could shoot, but how hard is it to point a gun and shoot?" he said.

The foreign fighter recalled a battle to retake Shchastya, a strategic town north of the separatist stronghold of Luhansk. As the Aidar Battalion pushed through a separatist military post erected under a bridge, Savchenko vanished. "She was nowhere. Just disappeared," he said.

Her treatment of prisoners was also questionable, according to the fighters' accounts. The foreign fighter described an incident when Savchenko used the butt of her rifle to cut the legs out from under a detainee whose hands were taped together. "He fell right on his f***ing ass," said the fighter, slamming his fist down on a bench to emphasize the power of the fall.

Savchenko's spokeswoman, Tetyana Protorchenko, dismissed those allegations as "nonsense" and said that "the soldier probably made it up." While Savchenko herself has not personally been accused of abusing prisoners before, the Aidar Battalion has been criticized for doing so throughout the conflict in Donbas. Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe mission monitoring the conflict have accused the Aidar Battalion of gross abuses, including abductions, unlawful detentions, ill-treatment, robbery, extortion, and possible executions. "Some of these amount to war crimes," Amnesty wrote in a September 2014 report.

Aidar's ranks are largely comprised of volunteers from Ukraine's eastern regions with ultranationalist and far-right views who were compelled to fight the pro-Russian insurgency sweeping through their hometowns. Savchenko's affiliation with the unit has led many to believe that she, too, holds far-right beliefs. A visit last month to the front line in eastern Ukraine, where she met with right-wing ideologue and Kremlin bogeyman Dmytro Yarosh, followed by a drop-in at the local base of Right Sector, another radical right-wing militia, only further convinced her critics.

On June 17, 2014, the Aidar Battalion was fighting a chaotic battle with separatist fighters from Ukraine's Luhansk region around the town of Metalist. Bullets whizzed through the air and mortars rained death down on both sides. The separatists had managed to hit two Aidar Battalion armored personnel carriers and a tank. In her court testimony, corroborated by video taken by her captors, Savchenko said that from where she was positioned, she could see smoke and fire coming from the vehicles. She dodged incoming fire and ran toward them, where she tended to wounded soldiers. But amid the bedlam she became separated from her unit. That's when her yellow scarf caught the eye of a separatist patrol, which took her captive. Aidar fighters were furious, but not surprised. "We f***ing told her all the time to stay [close] to us," the foreign Aidar fighter told me.

Three weeks later, Savchenko surfaced in the southern Russian city of Voronezh as a Russian prisoner. Later, she was brought to the southwestern city of Rostov-on-Don to stand trial for complicity in the murder of two Russian journalists.

*

Savchenko's capture sparked an ugly and protracted battle in court between Ukraine and Russia. It also became a diplomatic flashpoint, with Western leaders criticizing its proceedings as a show trial. Prosecutors charged her as an accessory to murder for directing the mortar attack that killed Igor Kornelyuk and Anton Voloshin, two Russian journalists working for state media who were reporting from behind separatist lines. They claimed her arrest came after she entered Russia illegally, disguised as a refugee seeking asylum. Outraged Ukrainian and Western leaders said the charges were absurd and called her capture an "abduction." Savchenko called it a "kidnapping."

In court, Savchenko's lawyers provided mobile-phone records that show she was taken to the eastern Ukrainian city of Luhansk at least an hour before the Russians were killed. Later, a Luhansk separatist revealed in an interview with the Meduza news website how he personally captured Savchenko before noon on June 17, 2014, and how his comrades had taken her to Voronezh.

By painting Savchenko as an unruly nationalist and murderer, the Kremlin was hoping to whip up Russian support for the war. The plan, however, had unintended consequences. Her defiance in the courtroom, where she spoke in Ukrainian, wore a shirt adorned with Ukraine's coat of arms, and sang the country's national anthem, thrust her into the international spotlight and gave Ukrainians a martyr to rally around. Savchenko publicly chided President Vladimir Putin and the Russian judicial system; she staged repeated hunger strikes, and refused to ask for clemency. She once leapt atop the bench in her courtroom cell to give the judge and presiding officials the finger.

"I was ready for them to kill me."

In her 2-by-2.5-meter prison cell, Savchenko remained steadfast and did not break. Her prison guards did not torture her, but they did beat her, she said. It was so bad that she mentally prepared herself for death. "I was ready for them to kill me," she said. She also endured psychological pressure and was under constant surveillance. Agents from Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB), the successor agency of the Soviet-era KGB, would often interrogate her.

She tried to make the lives of her guards a living hell, similar to the hell she was going through. Mostly she did that through civil disobedience. When they asked her to sit, she stood. When they told her to eat, she shoved the plate back at them. When they ordered her to turn around and put her arms behind her back to be handcuffed, she stared them in the face and offered her hands out front. "I never allowed [the Russians] to humiliate me as a person," she said. "I did not think I was below the jailer. He kept me here in captivity, but I could not understand why I was to bow down to him."

Russian prosecutors demanded a 23-year sentence for Savchenko. When the judge delivered the guilty verdict on March 22, Savchenko broke into song, forcing the court to take a recess ahead of her sentencing. After reconvening, the court sentenced her to 22 years behind bars.

*

Just after 3 a.m. on May 22, guards awoke Savchenko in her cell and ordered her to pack her bags. Wiping the sleep from her eyes, Savchenko didn't understand what was going on or know where she would be taken. She feared that preparations were being made to transport her to a maximum-security prison in Siberia, where she would likely labor away for nearly 12 hours a day, and then rot in a cold, dark hole at night. All the guards told her was to be ready to move when they came back for her.

For 72 hours she stirred in her cell, unable to sleep more than a few winks. When the guards returned, on May 25, they blindfolded her and threw her inside a van. She rode in the van for more than five hours, visionless and growing increasingly anxious. And then she heard the roar of airplane engines. When her guards removed her blindfold and opened the van doors, she was blinded again, this time by the light. But then, as her eyes adjusted, she saw a blue-and-yellow stripe in front of her. "I realized that it was a Ukrainian plane," Savchenko said.

After months of painstaking negotiations at the highest diplomatic levels between Kyiv and Moscow, Poroshenko had clandestinely dispatched his presidential jet to Rostov-on-Don to pick up Savchenko. Meanwhile, two Russian military intelligence servicemen, Yevgeny Yerofeyev and Aleksandr Aleksandrov, who had been captured by Ukrainian forces in May 2015 and then tried and found guilty of "terrorism," were being put on a Russian plane at a Kyiv airport before being flown to Moscow.

Meeting Savchenko on the tarmac in Rostov-on-Don was an officer from the Security Service of Ukraine. She didn't recognize him, but she knew the faces of two other people on board the plane -- presidential spokesman Svyatoslav Tseholko and Iryna Herashchenko, a member of the president's party in parliament. Only upon seeing them did Savchenko realize what was happening. Still, she was nervous. "Not until I saw the sky, until we crossed the Ukrainian border, did I feel free," she said. "I still thought that maybe [the Russians] could [shoot down] the plane."

A senior aide to Poroshenko who was directly involved in the negotiations would tell me in an interview days later that the final deal to free Savchenko came during late-night talks of the Normandy Four -- Poroshenko, Putin, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and French President Francois Hollande -- and after months of diplomatic wrangling that nearly fell apart on several occasions. Moscow, the senior aide said, was less interested in swapping Savchenko for Yerofeyev and Aleksandrov. What the Kremlin really wanted was to cut a three-way deal with Kyiv and Washington that would see notorious Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout and drug-trafficker Konstantin Yaroshenko, both of whom are serving long sentences in the United States, let go, the aide said. (Both Russian and U.S. officials previously scoffed at the idea, which was undoubtedly far-fetched.) Bout and Yaroshenko could be given a hero's welcome in Moscow, unlike Yerofeyev and Aleksandrov, whose capture was a public embarrassment for Russia.

Real progress in the Savchenko deal was only made this spring, according to the Poroshenko aide. Among the many red lines Ukraine drew was that in no way was Savchenko to appear in front of the media upon her release looking like a criminal, nor was she to be ordered to serve her sentence in Ukraine. "[The Russians] wanted to show her to journalists wearing handcuffs" during a final perp walk to the airplane, the senior aide said. Moscow eventually backed down on the demand. Poroshenko's office declined to say what, if any, concessions Kyiv made in the deal with the Kremlin.

*

During the autumn 2014 parliamentary elections, Ukrainian political parties stacked their candidate lists with war heroes who had fought in the east to give the appearance of bringing in reformers and fresh faces. The most sought-after was Savchenko, who topped the ticket of Tymoshenko's Fatherland party and was elected while she was still imprisoned.

Like Savchenko, Tymoshenko, the iconic leader of Ukraine's 2004 Orange Revolution, was once a political prisoner whose face adorned billboards across Kyiv. She spent more than two years behind bars until she was freed during the 2014 revolution. After being booed off stage by demonstrators during a speech she delivered from a wheelchair immediately after her release, she vanished into near obscurity. The parliamentary elections later that autumn marked Tymoshenko's return to politics. But she remains a divisive and unpopular political figure.

Oleksiy Ryabchin, a Fatherland deputy who was elected on the same ticket as Savchenko in 2014, said that "some people in the party weren't pleased with the idea of putting a political novice on the ticket, let alone in the top spot." But, he said, Tymoshenko "made everyone understand."

Even before she stepped off the plane in Kyiv, Savchenko, with her war-hero status, was touted as a challenger to President Poroshenko. Seen as untainted by rampant corruption and an outsider to the political elite, Savchenko's very lack of political experience was regarded as a virtue by a disenchanted electorate that increasingly views the current political establishment as being as corrupt and untrustworthy as the preceding one. Savchenko topped a June poll conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, which asked Ukrainians which of 25 leading politicians they trusted the most. Some 35 percent of Ukrainian adults said they trusted her, ahead of more seasoned politicians.

Ukrainians' widespread mistrust of their leaders is understandable. The government has been disbanded and reassembled twice since the revolution; once-popular reformist officials such as U.S.-born Finance Minister Natalie Jaresko and Lithuanian-born Economy Minister Aivaras Abromavicius have left its ranks, complaining of persistent corruption and the intentional blocking of important reforms by the president's loyalists; and Poroshenko has consolidated his power by engineering the appointments of his cronies Volodymyr Hroysman and Yuriy Lutsenko to the posts of prime minister and prosecutor-general, respectively.

"Up to 95 percent of this government is not of the people," Savchenko told me. "People gave so much [in the revolution], and those who came to the government, they don't do anything. Who is controlling everything there, I still don't know."

Poroshenko has good reason to fear Savchenko. A Gallup poll from December 2015 shows his popularity has plunged to 17 percent, below even that of Yanukovych before he was deposed during the uprising in February 2014. If a presidential election in Ukraine was to be pushed forward from 2019 to this year or next, "Savchenko would be the top contender," said Volodymyr Fesenko, a prominent Ukrainian political analyst and director of the Center of Applied Political Research at Penta, a Kyiv think tank.

Ready or not, Savchenko has said she is willing to step into the role if she should have to. "Ukrainians, if you want me to be president, then, fine, I will be president," she told a press conference in Kyiv on May 27. But, she added, "I can't say that I want to."

As a politician, Savchenko has said she will focus on three issues: national security, Ukrainian military reforms, and the release of Ukrainians imprisoned in Russia. Around 30 Ukrainians are currently sitting in Russian prison cells on charges widely considered to be politically motivated.

But her main priority, for now, she said, is to try to learn more about politics and how she can be an effective deputy. Ryabchin, the Fatherland lawmaker, said Savchenko often comes to him and others in the party with questions about parliamentary procedures. "She's not afraid to ask questions...because she wants to understand how the system operates," he said.

Savchenko has also joined parliament's National Security and Defense Committee. According to Ryabchin, as well as another Fatherland lawmaker who asked to remain anonymous because he was commenting on a closed-door conversation, strings were ready to be pulled for her to head the committee, until Savchenko herself shut that down. "She wants to climb the political ranks the same way in which she climbed the military ranks -- working her way up from the bottom," Ryabchin said.

*

Savchenko has had little time to relax since returning home. She said she sleeps poorly, on average three or four hours a night. She struggles with nightmares when she does manage to get some sleep. With heavy, dark circles under her eyes, the exhaustion is visible on her face. A steady supply of coffee, energy drinks, and cigarettes keeps her going, she told me.

Fatigue caught up with her during a recent session of parliament's National Security and Defense Committee. A video filmed by Ukrainian media showed an exhausted Savchenko dozing off, her hands pressed against her head the only things keeping her face from smacking into the table. Russian propaganda had a field day with the footage, claiming Savchenko was hungover from a night of partying with friends. Critics accused her of being a hypocrite, since on her first day as a deputy in parliament Savchenko attacked lawmakers for their lack of efficiency, calling them "lazy schoolchildren who shirk their work."

"I'm back and will not let you forget -- you who sit in these seats in parliament -- about all those guys, who laid down their lives for the country," Savchenko said. "I tell you that nobody is forgotten, nothing is forgotten. Nothing is forgiven. And the Ukrainian people will not let us sit in these seats if we betray them."

Many Ukrainians seemed to love the public scolding. Video footage of it played on prime-time news and was widely shared on social media. "Savchenko obviously has strong political inclinations," analyst Fesenko said. "She has shown that she has strong oratorical skills...she has very strong political power."

She will need that power to be successful inside the halls of Ukraine's often raucous parliament, a notoriously opaque body where lawmakers frequently come to blows over legislation; where business is often conducted through political horse-trading; and where the impressively dexterous fingers of deputies partake in what's known as piano voting -- when a deputy casts his or her vote before reaching to another chair to vote for absent colleagues. During a session on July 5, Savchenko showed she was prepared to behave in as unruly a manner as her more experienced colleagues, commandeering the speaker's chair while other Fatherland deputies and allies from the populist Radical Party occupied the rostrum, forcing the day's session to end early.

Her brazenness, eccentricity, and shoot-from-the-hip manner of speaking may well eventually wear thin on a public more accustomed to polished politicians in flashy suits. She is "emotional and impulsive," Fesenko said, and those characteristics will "likely create problems for her." And history has showed, Fesenko said, that "exaggerated political expectations inevitably turn into big disappointment."

The list of examples in Ukraine is long. He pointed to Poroshenko as well as former President Viktor Yushchenko, who rose to power from the Orange Revolution in 2004 only to leave Ukrainians disillusioned after failing to deliver on his promises to stem corruption, arrest criminals, and put Ukraine on a European path. Or former Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who, like Poroshenko, strode into office on the coattails of the 2014 revolution and has since seen his popularity plunge -- so much so, in fact, that he was forced to resign this spring.

Savchenko's critics have already begun the mud-hurling. One popular accusation is that she was sent back to Kyiv to spy for Moscow and foment a revolution to destabilize Ukraine. "There is nothing we can do about the Savchenko factor. Putin sent her to us to provoke a revolution," said Vadym Rabinovich, a member of the Opposition Bloc, a party controlled by powerful oligarchs with ties to Russian businesses and Yanukovych.

Savchenko told me that she was approached several times by Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB), admitting that they did offer her deals to flip and join the Russian side. But she said agents stopped bothering her when they saw that she wouldn't break.

Those assurances aren't enough for some, though. Some politicians and political observers within Ukraine believe that Savchenko may be a kind of Manchurian candidate, like the character in Richard Condon's 1959 political thriller of the same name who is brainwashed in a Soviet psychological research facility to become a sleeper assassin. The FSB "feeds prisoners with specific information," said Taras Berezovets, a prominent Ukrainian political analyst who once worked as a strategist for Tymoshenko and is currently the director of Berta Communications, a Kyiv-based political consultancy. "So in that way, Savchenko definitely has a [distorted] picture" of reality, he said.

While Berezovets admitted it's far-fetched to think Savchenko was indoctrinated by the FSB and sent home to carry out a political assassination, he said that considering her unpredictability and tendency to lean to the radical, she's likely to foment chaos and rebellion. "Nadia definitely presents a clear and present danger to [Ukraine's] national security," Berezovets said.

What might eventually prove to be her political undoing is her alliance with Tymoshenko. Savchenko's snubbing of Tymoshenko at the airport, where she refused to take the bouquet of flowers, may well prove to be emblematic of their relationship -- and a harbinger of what's to come. Berezovets said there just isn't enough room for two strong female personalities at the top of the party. "Yulia is a strong, charismatic leader who will not accept her alter ego," he said, referring to Savchenko.

"Before you make a good friend, you should have a fight over a girl, beat each other's faces in, share a bottle of vodka – and then you will become good friends."

If there has been turmoil in Fatherland between the two women, the party has hidden it well. Tymoshenko has stayed away from Savchenko in public, while Savchenko has tried to avoid discussing their relationship with reporters. Tymoshenko's party wasn't her first choice, Savchenko told me, but it "isn't the worst" and she's staying -- for now.

What's more important, Savchenko said, is to push for fresh parliamentary elections, a campaign that is backed not only by Ukraine's nationalists, but also increasingly by young revolutionaries who entered parliament with her in 2014. On July 9, a group of them, including prominent journalists and activists-turned-politicians Serhiy Leshchenko and Mustafa Nayyem, the man many credit with starting the Maidan revolution with a Facebook post, broke off from established political factions to form two new parties.

Poroshenko and his allies in parliament oppose early elections, arguing that a vote would aggravate Ukraine's economic crisis. But they have another reason to not support the idea -- the president's popularity has plunged in recent months, and an early vote would likely leave them with far fewer seats in parliament and more power in the hands of their political opposition.

Something that all sides agree on is that the war that has cost more than 9,400 lives since it began in April 2014 must end and reconciliation needs to begin. But how exactly this should happen is the subject of fierce debate. Savchenko has said she wants Kyiv to hold direct talks with separatist leaders Aleksandr Zakharchenko and Igor Plotnitsky. She is prepared to do it personally if need be, she explained, breaking from Poroshenko's and the government's official position to not negotiate with "terrorists." Of course, the separatists would have to agree to sit down with her, too. Zakharchenko has said he'd shoot her if she set foot in Donetsk.

Savchenko is not to be deterred. "[In Ukraine], we say: 'Before you make a good friend, you should have a fight over a girl, beat each other's faces in, share a bottle of vodka -- and then you will become good friends,'" Savchenko said. "We have already fought for a girl -- Ukraine. And we have already beaten each other's faces in. So what we need to do is to share a bottle of vodka and become good friends. We are, however, still just beating each other's faces in."

Kyiv's plan to get the separatists to bend to its will has been one of isolation, cutting off economic, financial, and political ties with the occupied territories. It's a punitive measure that has embittered eastern Ukrainians, divided families, and made life a nightmare for those inside occupied Donetsk and Luhansk. Savchenko said Kyiv made a mistake in not reaching out to the east of the country at the start of the conflict and allowing them a voice in national politics. "We need to make sure that they realize that they are ours, too, that they are Ukrainians, and that we should unite against Russia, our enemy, to win [the war]," she said. She supports a broad amnesty for separatist fighters, a point of serious contention in the capital.

Here, Savchenko also breaks with strident, militaristic nationalists who have picketed parliament over the proposed amnesty and who prefer defeating their enemy on the battlefield to a peaceful resolution. Thirty-one percent of Ukrainians support the continuation of the "antiterrorist operation" in the east, as Kyiv calls it, until the occupied regions are back under government control, according to a June poll by the Razumkov Center, a Kyiv-based think tank that researches public policy.

*

On a recent Friday afternoon, a motley crowd of academics, celebrities, diplomats, politicians, and journalists from the United States, Ukraine, and Western European states gathered for a barbecue at the residence of Geoffrey Pyatt, the U.S. ambassador to Kyiv. All had come to celebrate America's Independence Day. Red, white, and blue banners hung from the residence's upper balcony, posters trumpeting the beauty of American national parks lined the landscaped yard, and a pop-up Jack Daniels bar served whiskey-colas.

From above a group of partygoers rose the thick head of towering boxing champion turned Mayor of Kyiv Vitali Klitschko, who posed for selfies with his admirers. Nearby stood Yuriy Boyko, the current leader of the Opposition Bloc and Yanukovych's former energy minister, looking dapper with his coat thrown over his shoulder as he chatted to businessmen. Beside a beer keg was a group of FBI investigators who had arrived to assist their Ukrainian colleagues with probes into high-level corruption.

As the alcohol flowed, the conversations grew louder. The smell of charred hamburgers mixed with the pungent aroma of sweating bodies as the summer sun glared down on us all. Hiding from the commotion was a woman standing in the shade of a large tree and pecking at a plate of salad and flame-grilled fare. When I approached Savchenko, her face was twisted with the uncertainty of someone who wasn't sure they belonged.

"What do you think of all this?" I asked her.

"I don't know what's happening here," she said, shaking her head. "It's like something I've seen in American films."

After being approached by a few guests interested not in conversation but in having their photos taken with her, she had withdrawn to this concealed corner of the property, standing farther from the party than even the security guard walking the perimeter. People didn't seem to know quite what to say to her, and she didn't know what to say to them. While in prison, she had been "our Nadia." But now free, she was like a monument beside which one smiles and snaps a picture for posterity's sake.

Later, as I watched Savchenko from across the yard, I thought about the public's comparison of her to Joan of Arc, and her own comparison to Danko, a character in Soviet author Maksim Gorky's short story, Danko's Burning Heart, which she herself brought up in our first interview. "Danko tore his heart out of his chest to illuminate the way for people, and then he fell down and his heart burst into sparks," Savchenko said. "I am also ready for such self-sacrifice."

Now, though, seeing her standing there in the shadows, she just looked exhausted, overwhelmed, and alone. She looked a lot like an ordinary woman eating a hot dog.

Olena Removska, from RFE/RL's Ukrainian Service, contributed to this story.