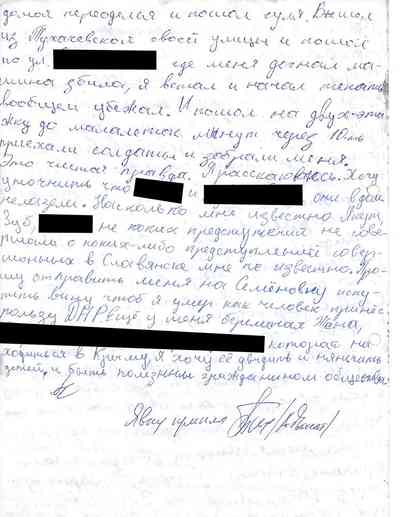

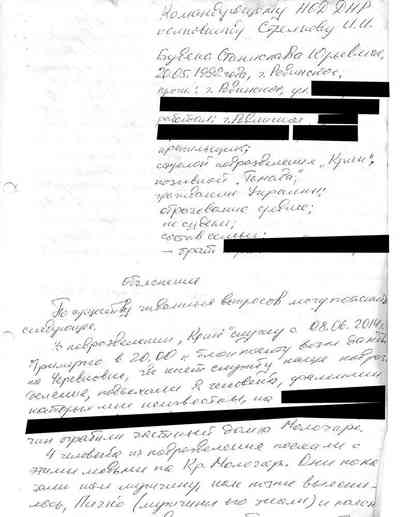

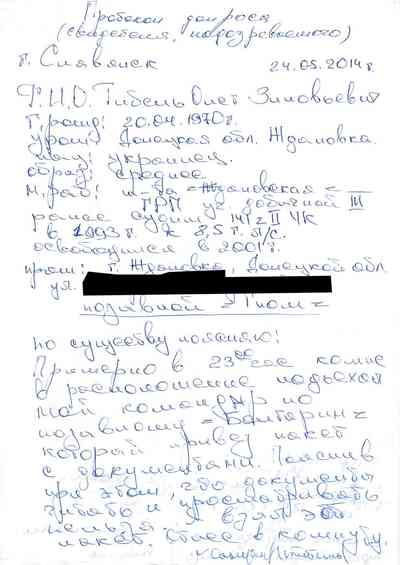

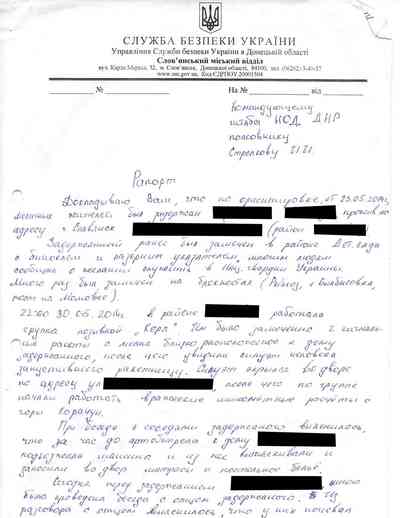

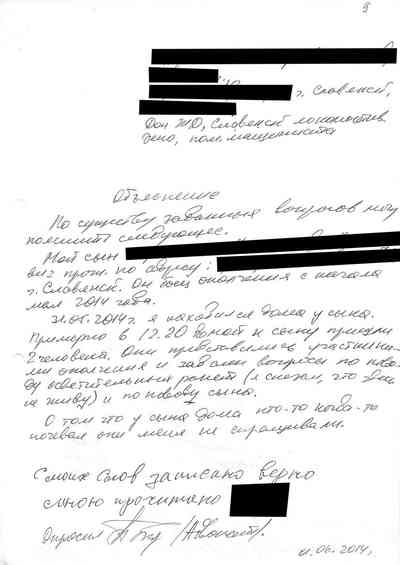

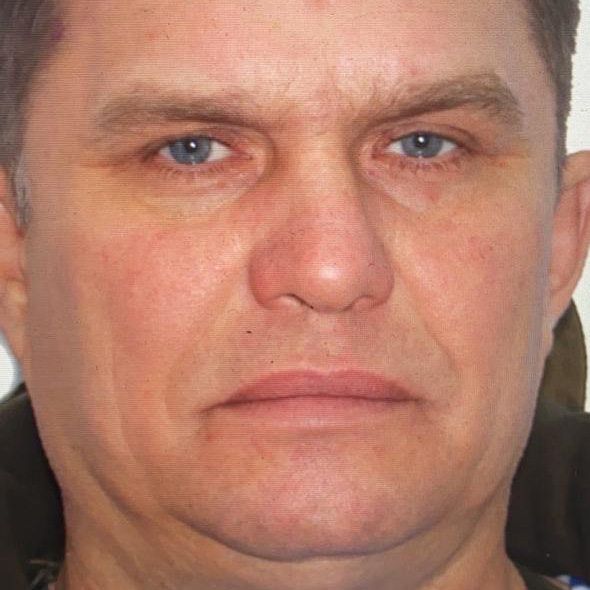

slovyansk, ukraine — The Russia-backed gunmen came and hauled away Oleksiy Pichko on the afternoon of June 17, 2014, three days after he allegedly broke into a neighbor’s home in a rundown district on the outskirts of Slovyansk, in eastern Ukraine, and stole two shirts and a pair of pants.

The 30-year-old Pichko, a civilian, was taken to a gloomy two-story building surrounded by armed guards and barricades. He was interrogated, forced to write a confession, and summarily shot to death by a firing squad of Russia-backed separatists who had seized control of the city. His executioners discarded his body on a battlefield of the war raging between them and Ukrainian forces, where it could be blown to bits by exploding artillery shells, according to family members and friends who sought out his whereabouts when he was taken and looked for his body after learning of his death.

He wasn’t the only person in Slovyansk to meet such a fate.

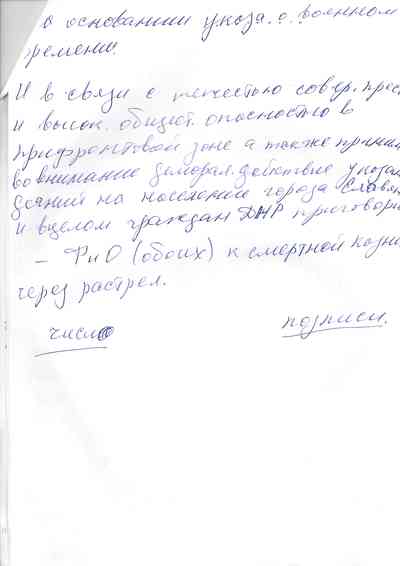

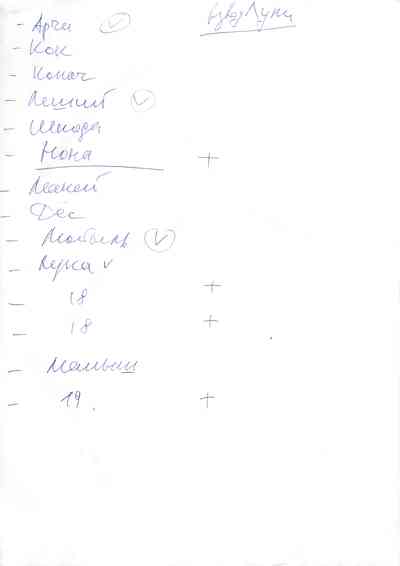

Three weeks earlier, on May 25, two Ukrainian men who had joined the Russia-backed separatist fight, Dmytro Slavov, 32 , and Mykola Lukyanov, 25, were arrested by their comrades-in-arms and dragged to the same guarded building in the center of Slovyansk, a city in Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast near the heart of the coal-mining region called the Donbas. Accused of marauding, armed robbery, kidnapping, abandonment of their military positions, and trying to cover up their activities, they were also interrogated before being lined up and executed by a firing squad, according to family members, acquaintances, former detainees, and two Slovyansk residents with knowledge of their so-called “trials” and deaths.

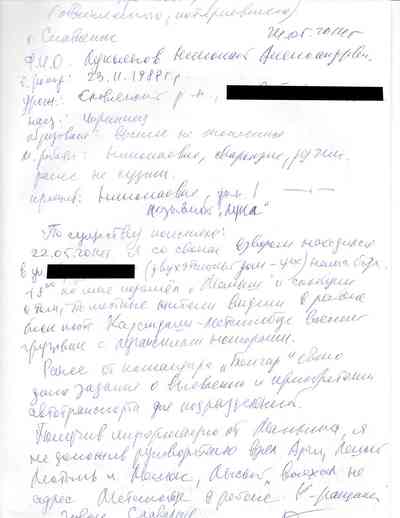

Courtesy of Maria Pichko

According to documents, the fates of all three men were decided by so-called “military tribunals” established by Igor Girkin, a former Russian intelligence officer better known at the time by his nom de guerre Igor Strelkov, on the basis of a draconian law conceived by dictator Josef Stalin and imposed shortly after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in World War II. The decree handed down by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R. on June 22, 1941, and invoked by Girkin and his Russia-backed forces in 2014, allowed for capital punishment -- a penalty abolished by Ukraine in 2000 and not imposed in Russia, where a moratorium has been in place since 1996 -- for crimes Girkin called “grave” but ranged from petty theft to murder.

Girkin was aided by at least nine men who participated in the “military tribunals” and condemned Pichko, Slavov, and Lukyanov to death. But those nine men have received far less attention than Girkin — who is also one of four defendants charged with murder by Dutch prosecutors for their alleged roles in the July 17, 2014 shoot-down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over the battlefields of eastern Ukraine, which killed all 298 people on board. Several have remained unidentified, and their specific roles in these “tribunals” undisclosed.

Until now.

Using documents recovered from Girkin’s former office at the city’s security service headquarters, open-source investigative methods, and interviews with dozens of alleged torture victims, witnesses, and family members of the victims, RFE/RL has determined the identities of and new details about seven of the nine men who served on Girkin’s “military tribunals” in Slovyansk.

Evgeny Feldman

On top of identifying the men, RFE/RL has found that one of them is tied through a Moscow-based organization for Russia-backed fighters to Vladislav Surkov, one of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s closest aides at the time of the executions and the architect of the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy. Another man is a senior military figure in the Russia-backed separatist forces in Donetsk. In addition, most of them appear to have been granted Russian passports and safe haven in either Russia or areas of Ukraine currently controlled by Moscow or by Russia-backed forces, effectively placing them under the protection of the Russian state and beyond the reach of Ukrainian and international law enforcement.

Many of the men are married and have resumed a more-or-less normal life, running local businesses and keeping active social media profiles where they share photographs of family gatherings and summer holidays in Russia, Russian-controlled Crimea, or the sections of the Donbas still held by the Russia-backed forces. Some are fathers and grandfathers, pictured embracing children and grandchildren born after the days of the firing-squad executions.

The iron-fisted tactics employed by Girkin in Slovyansk have been reported previously and Girkin himself has admitted to overseeing the executions of Pichko, Lukyanov, and Slavov, as well as at least three other men. His most recent comments on executions in eastern Ukraine came in May, when he told a Ukrainian journalist -- in an interview that caused a firestorm in Ukraine -- that he had executed one of the six men himself.

The new information uncovered by RFE/RL about the executioners adds to an ever-growing pile of evidence of what experts believe may constitute war crimes by Russia and the separatists it backs with soldiers, weapons, money, and political support. It comes as Ukraine pursues justice through cases in its own courts and legal claims against the Russian state in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and International Criminal Court (ICC).

Varvara Pakhomenko, head of mission in Ukraine for Geneva Call, a human rights group focused on the protection of civilians in armed conflicts, reviewed the documents from Slovyansk. Speaking generally about summary executions in war zones, she told RFE/RL that “the death penalty is possible in exceptional circumstances for very serious crimes, but only if a fair and independent trial exists.”

“If not, it may constitute a war crime,” Pakhomenko said.

Wayne Jordash, a leading expert in international human rights law, said the Pichko "trial" documents lack "critical facts" that could provide more clarity, but that the sentence appears "to be disproportionate to the crime."

"Executing an individual for a petty crime would not seem to satisfy the requirement for a fair trial," said Jordash, a managing partner at the legal firm Global Rights Compliance. "In these circumstances, there is at least prima facie evidence of a war crime."

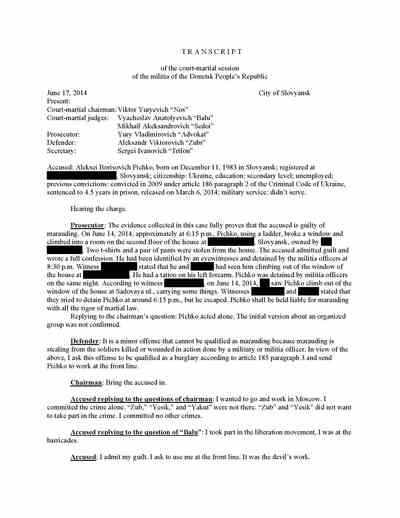

What The Documents Show

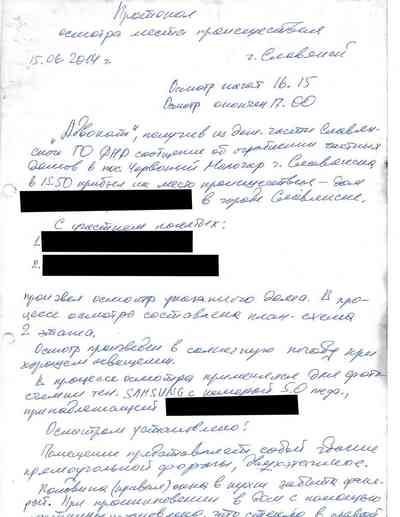

The dozens of documents from which this investigation derives were recovered by reporters from Girkin’s Slovyansk headquarters on July 7, 2014, two days after he and his Russia-backed forces retreated from the city to Donetsk, the regional capital, following weeks of heavy artillery bombardment from Ukrainian forces.

The documents were found lying on the desks where Girkin and the fighters under his command once planned their military attacks and strewn across the floors of the halls through which they dragged numerous prisoners, including civilians and journalists, who were falsely accused of various crimes, such as spying for Kyiv. The records were scattered about rooms where Girkin’s men carried out their summary justice against those who ran afoul of them.

As part of this investigation, RFE/RL is making the complete collection of the documents available to the public for the first time so that they may be further analyzed by journalists, researchers, and law enforcement officials who are trying to make sense of a war that has killed more than 13,000 people and is now in its seventh year, with no end in sight. Several of the key documents have been translated from Russian into English and Ukrainian.

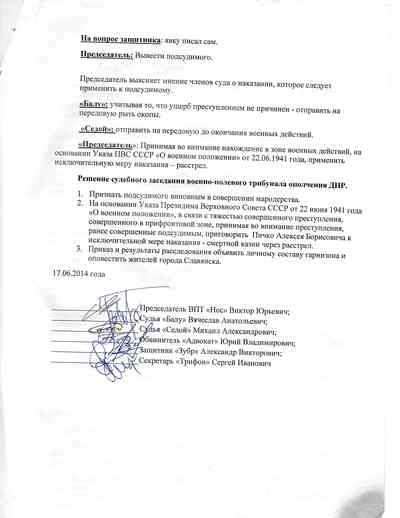

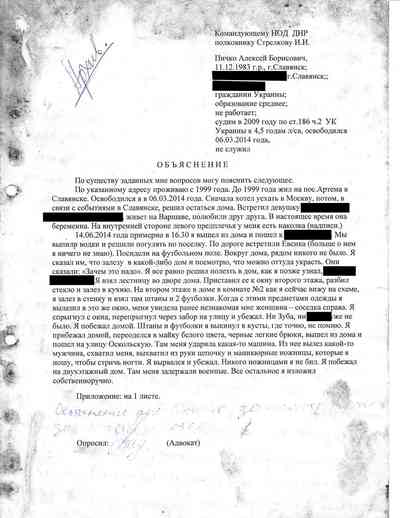

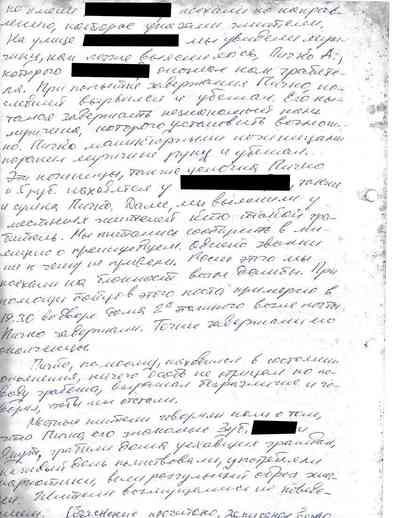

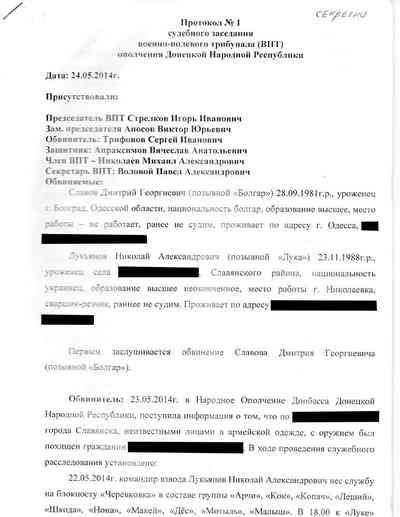

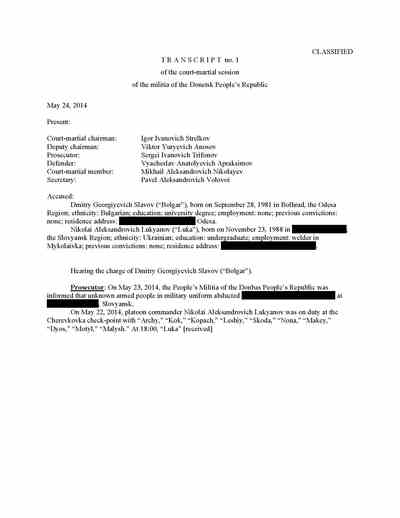

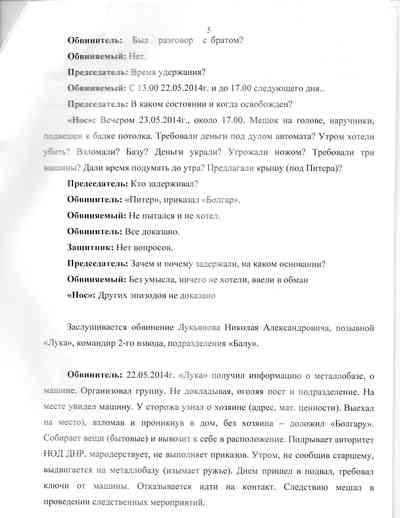

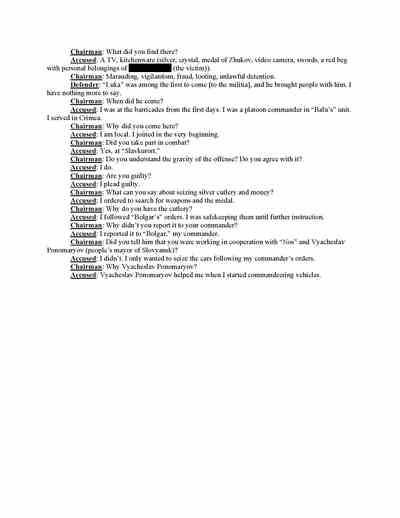

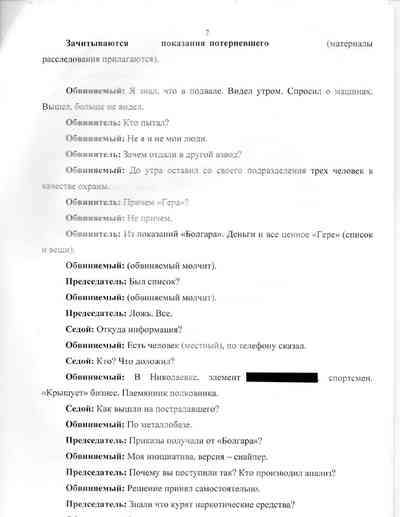

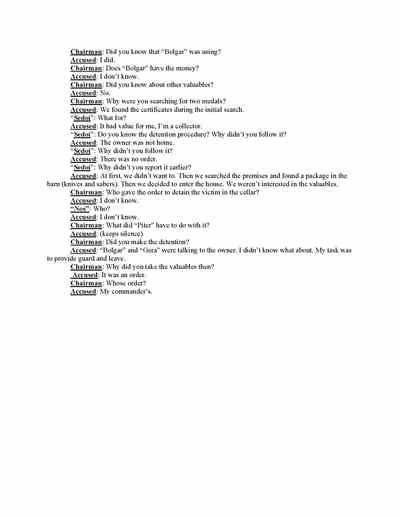

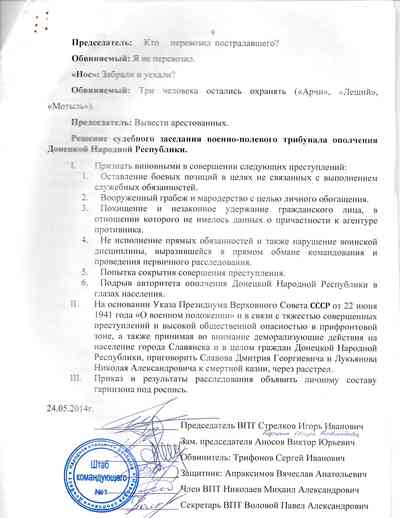

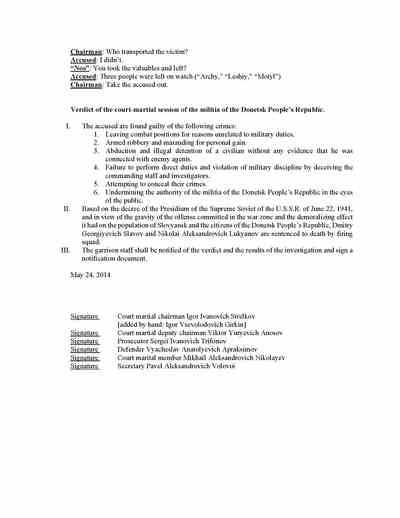

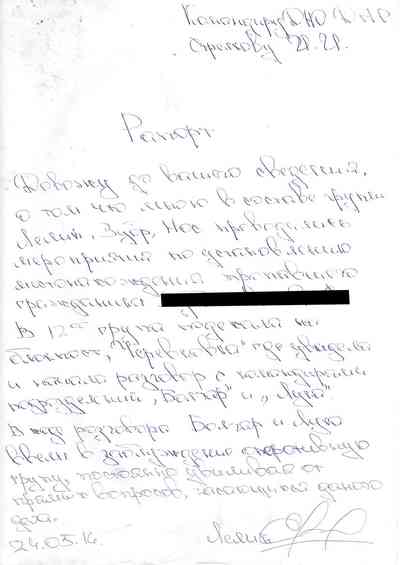

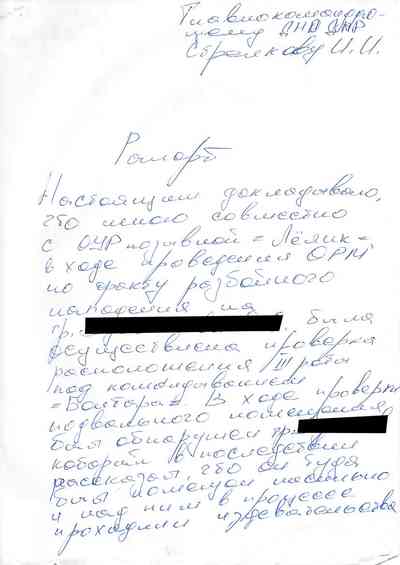

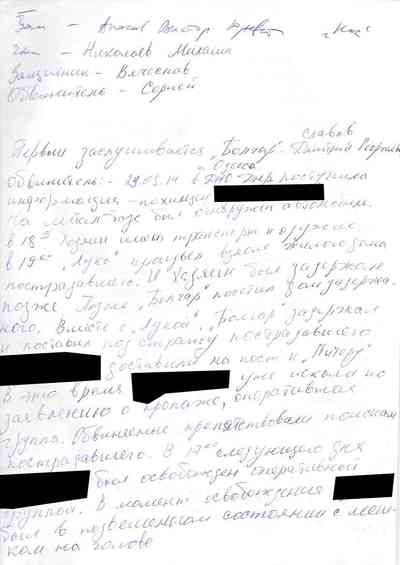

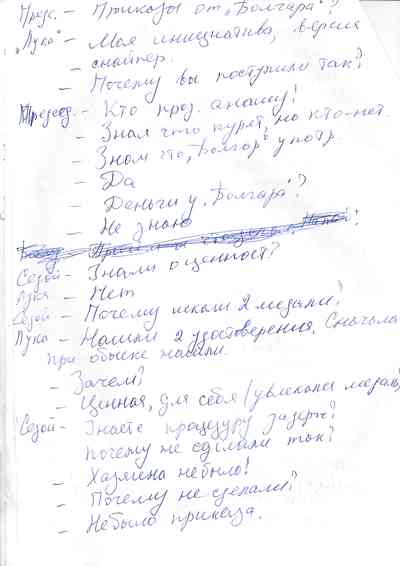

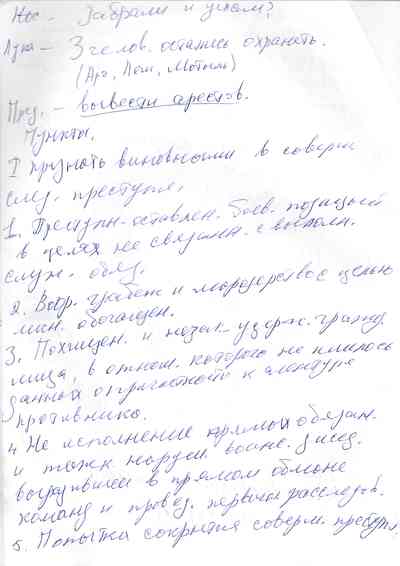

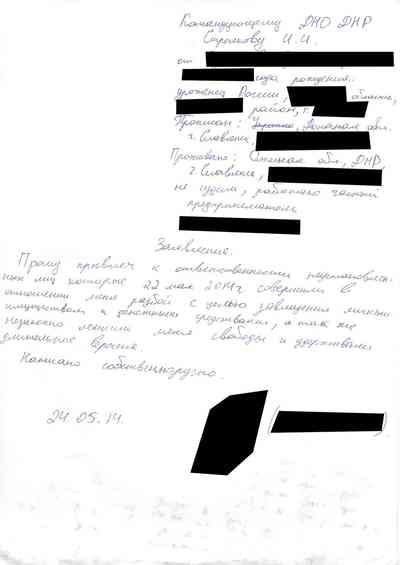

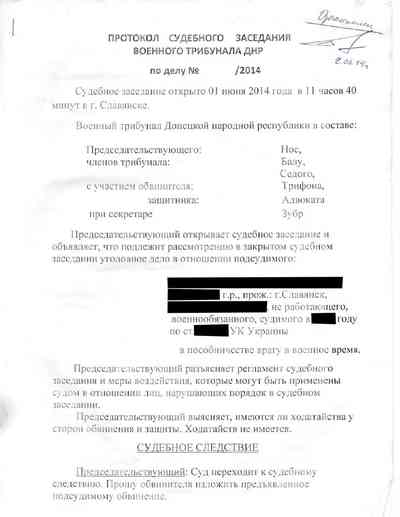

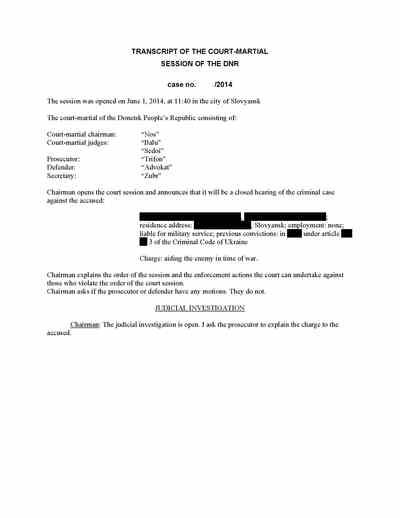

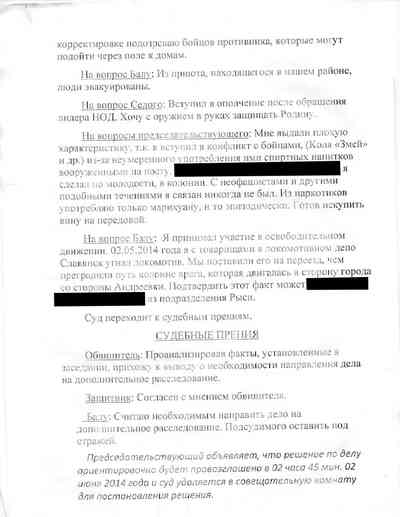

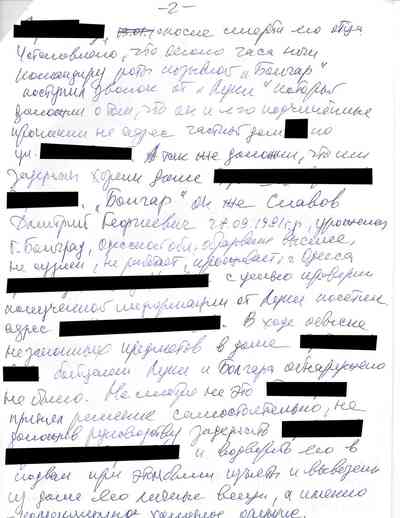

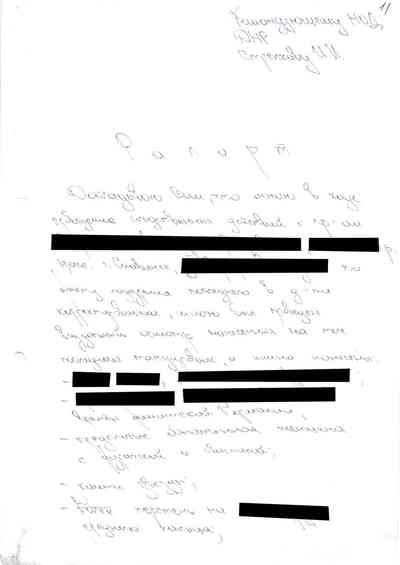

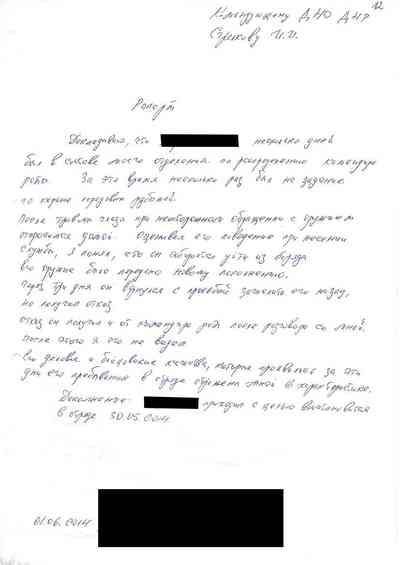

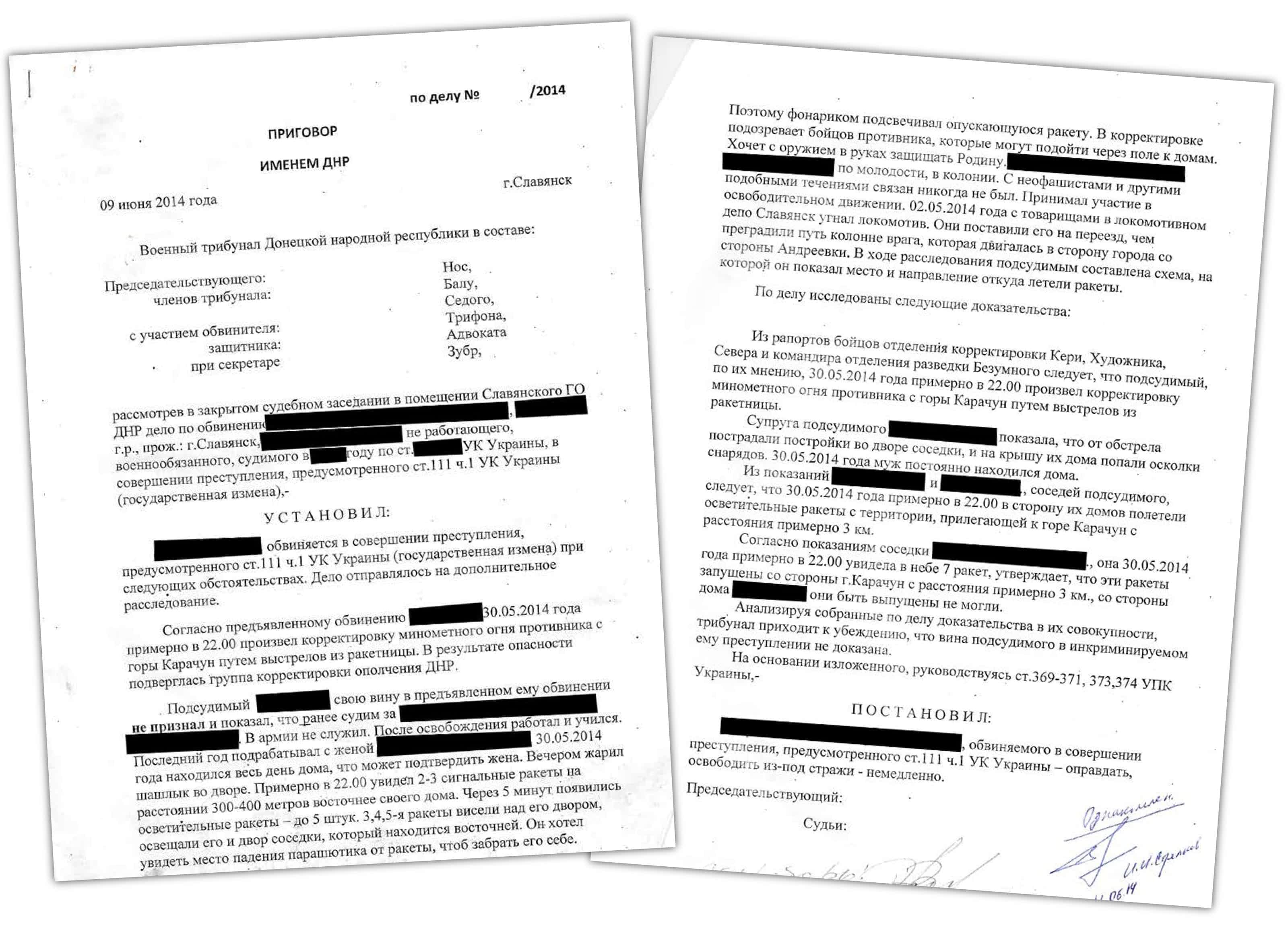

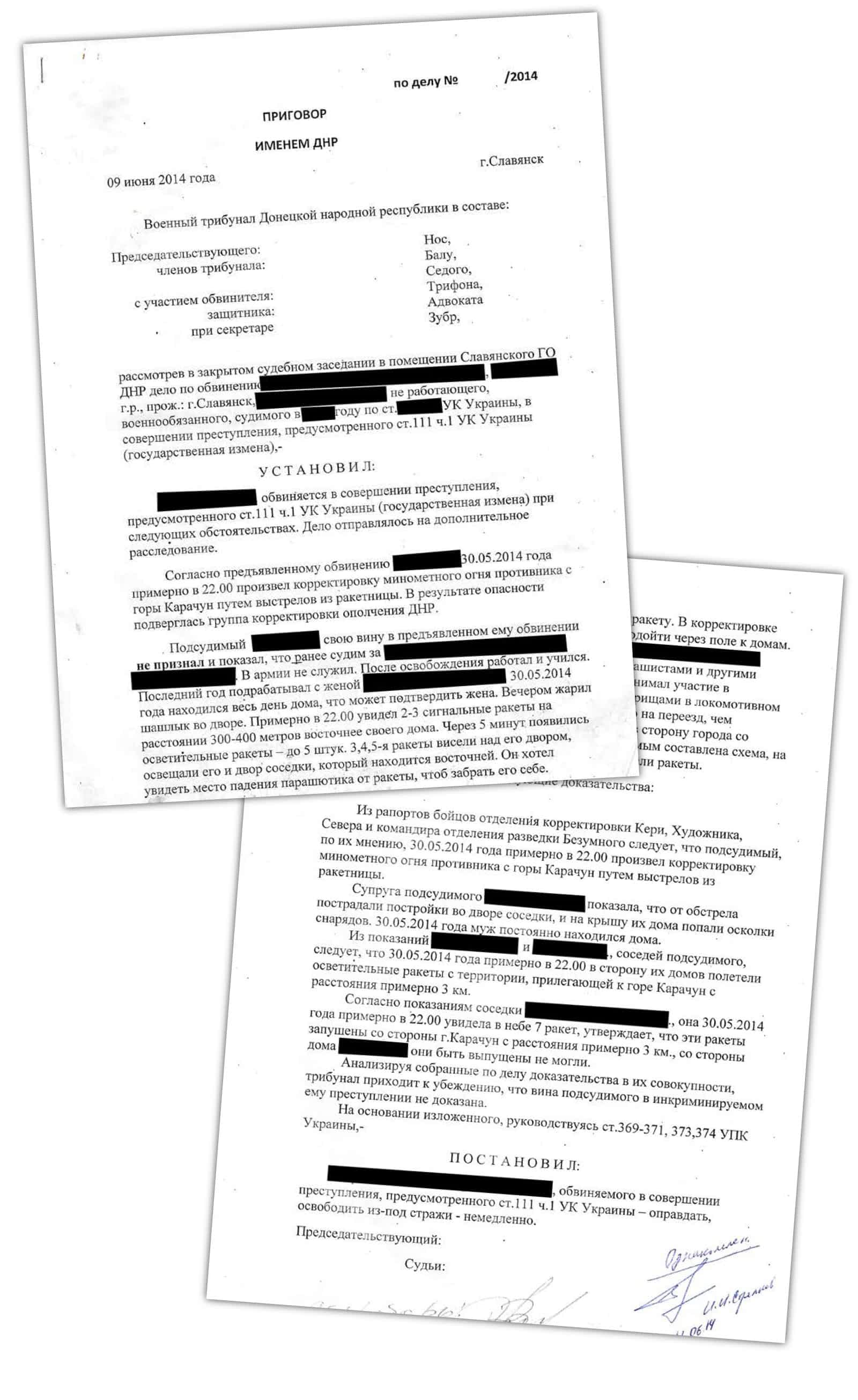

The documents include detailed, typed records of the “military tribunal” proceedings in which Pichko, and separately Lukyanov and Slavov, were condemned to death.

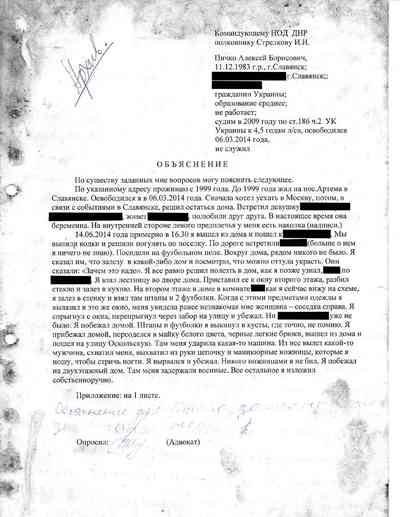

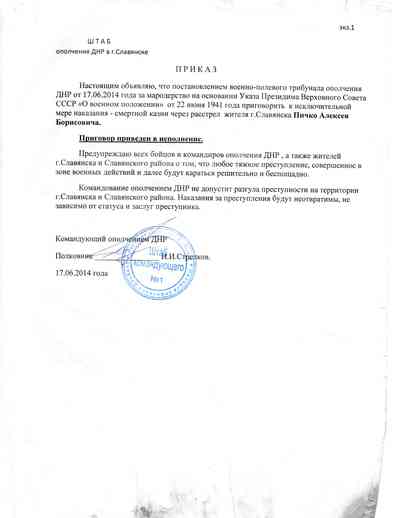

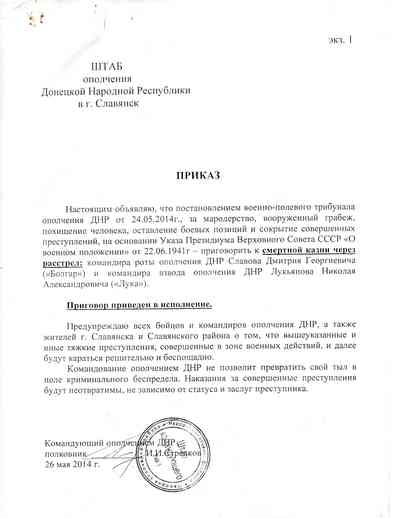

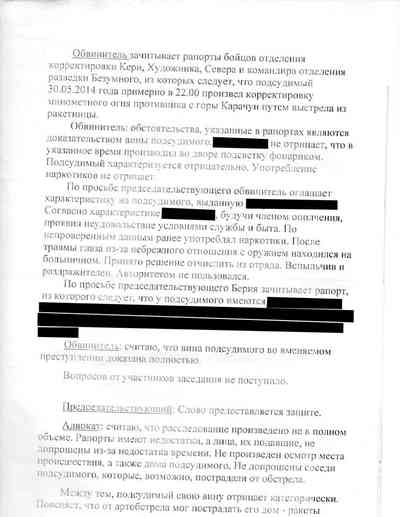

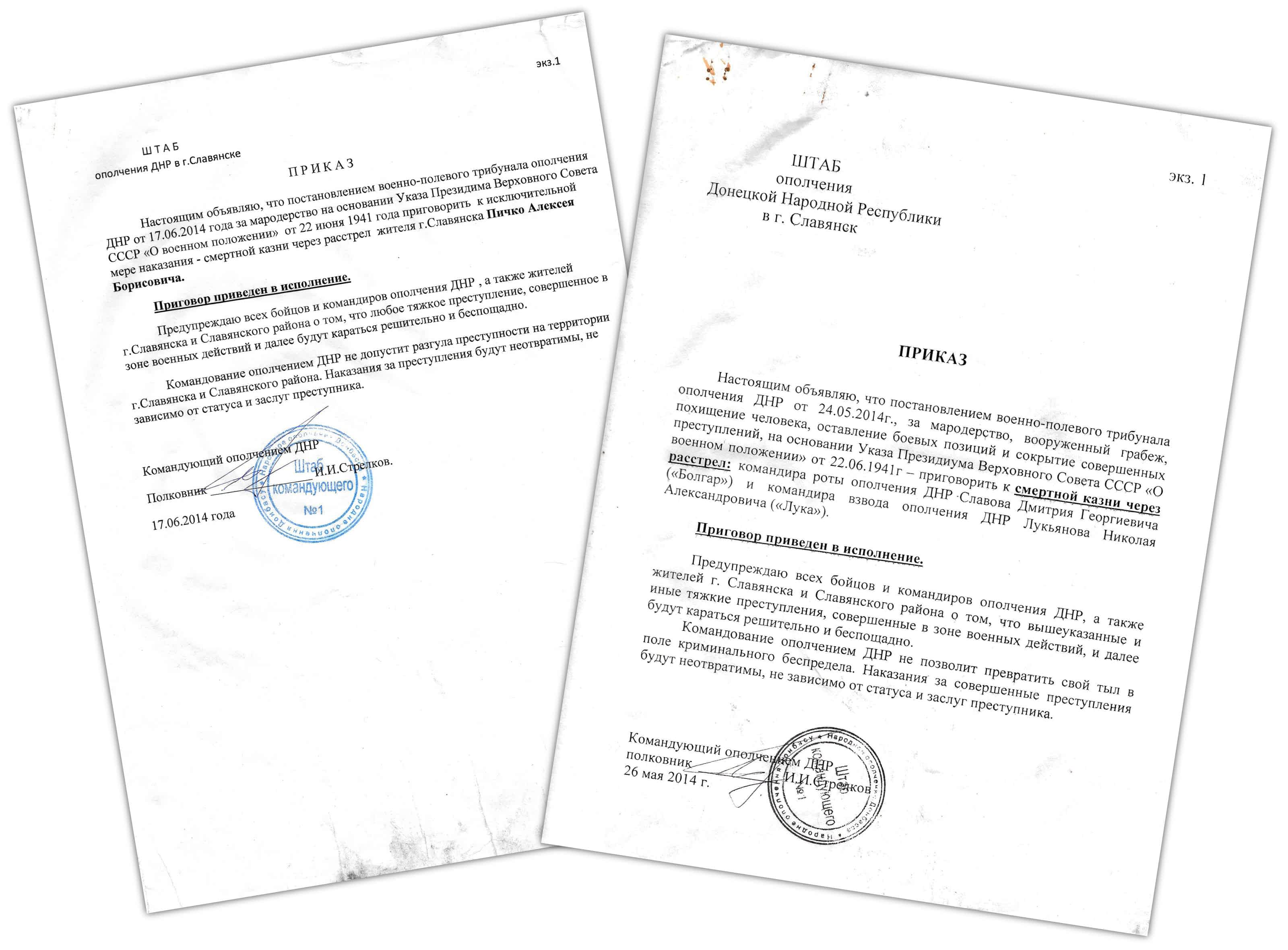

The document on the left is the order for Slovyansk civilian Oleksiy Pichko’s execution issued by Igor Girkin, the Russian commander of Moscow-backed separatists who seized the Ukrainian city. On the right is the order signed by Girkin for the executions of Dmytro Slavov and Mykola Lukyanov, who fought alongside Russia-backed separatists.

- 1 As justification for the executions, Girkin cites a June 1941 wartime decree handed down by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R.

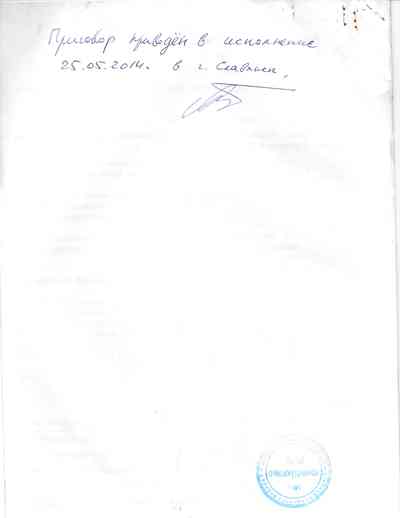

- 2 The orders state that the executions have been carried out.

- 3 Girkin warns that any “grave crimes committed in the war zone will be punished decisively and without mercy.”

- 4 Girkin signs off on the execution order using his nom de guerre, Strelkov.

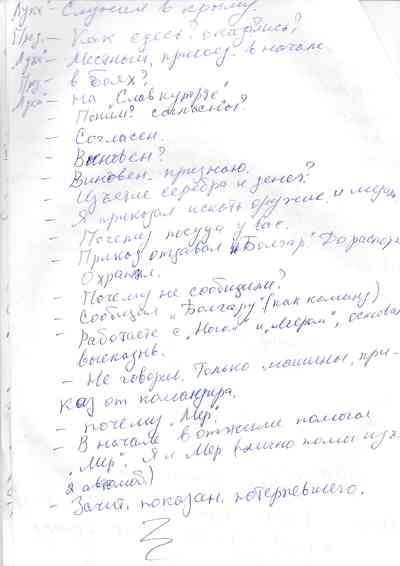

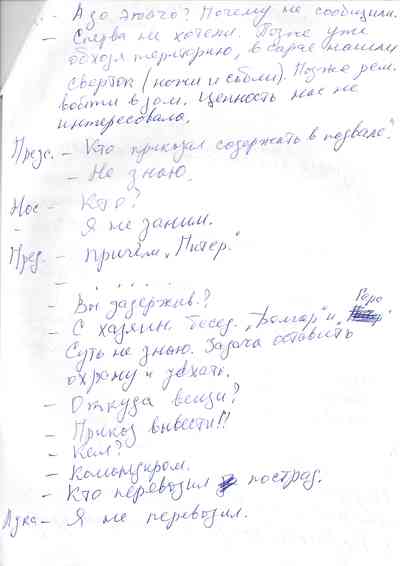

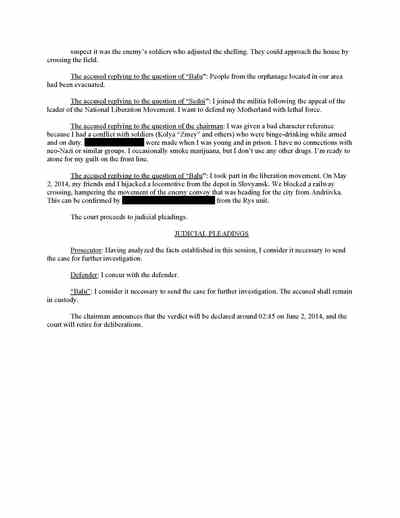

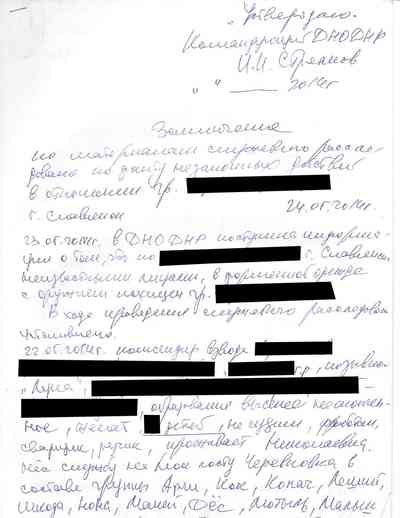

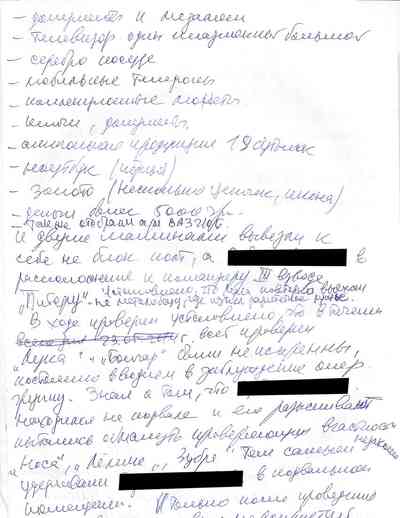

They also include a third case involving a Ukrainian man who narrowly escaped a firing squad. He was acquitted of treason charges brought against him for allegedly betraying the separatists’ fighting positions when he shined a flashlight near the battlefield during an artillery exchange with Ukrainian forces.

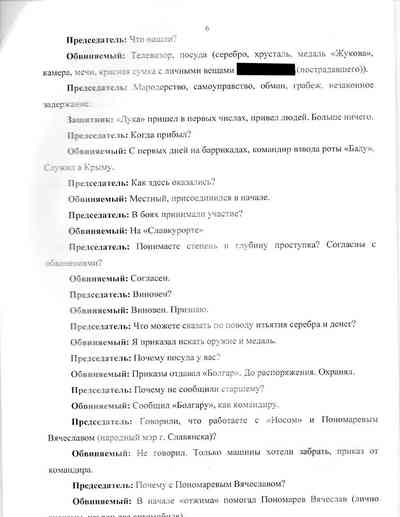

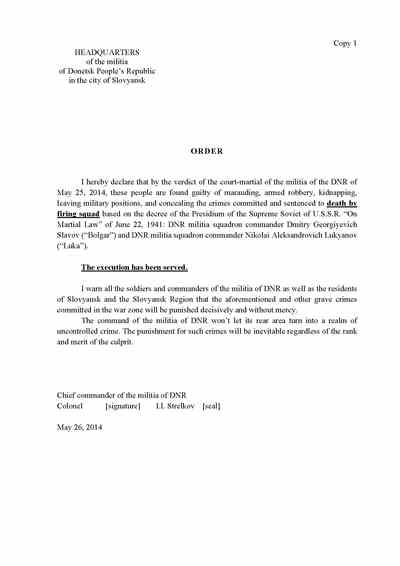

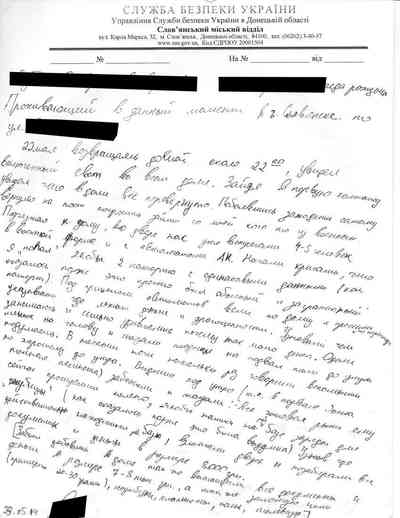

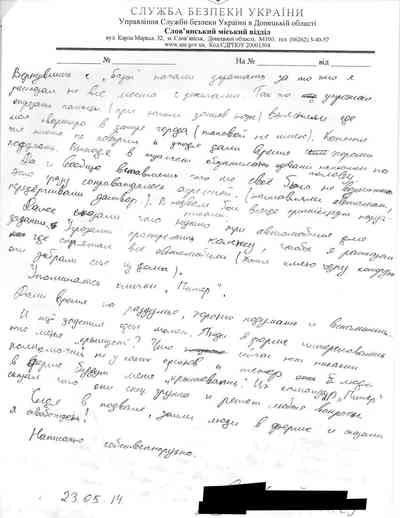

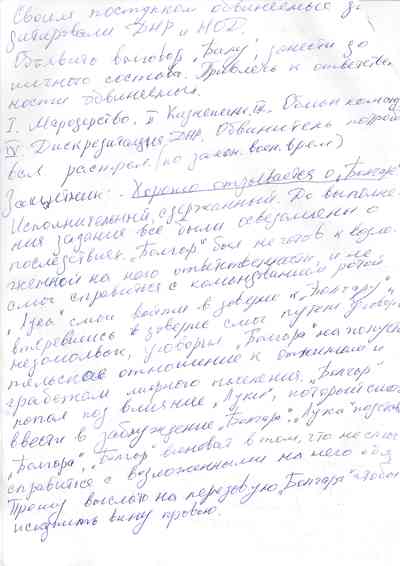

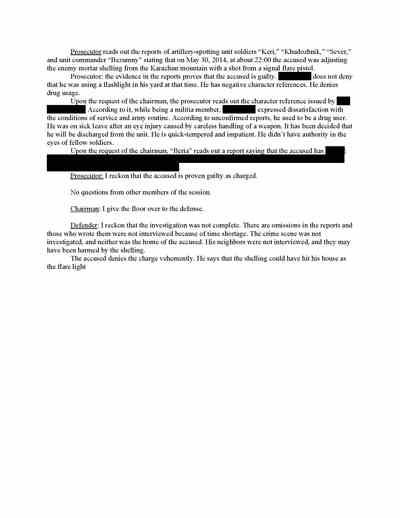

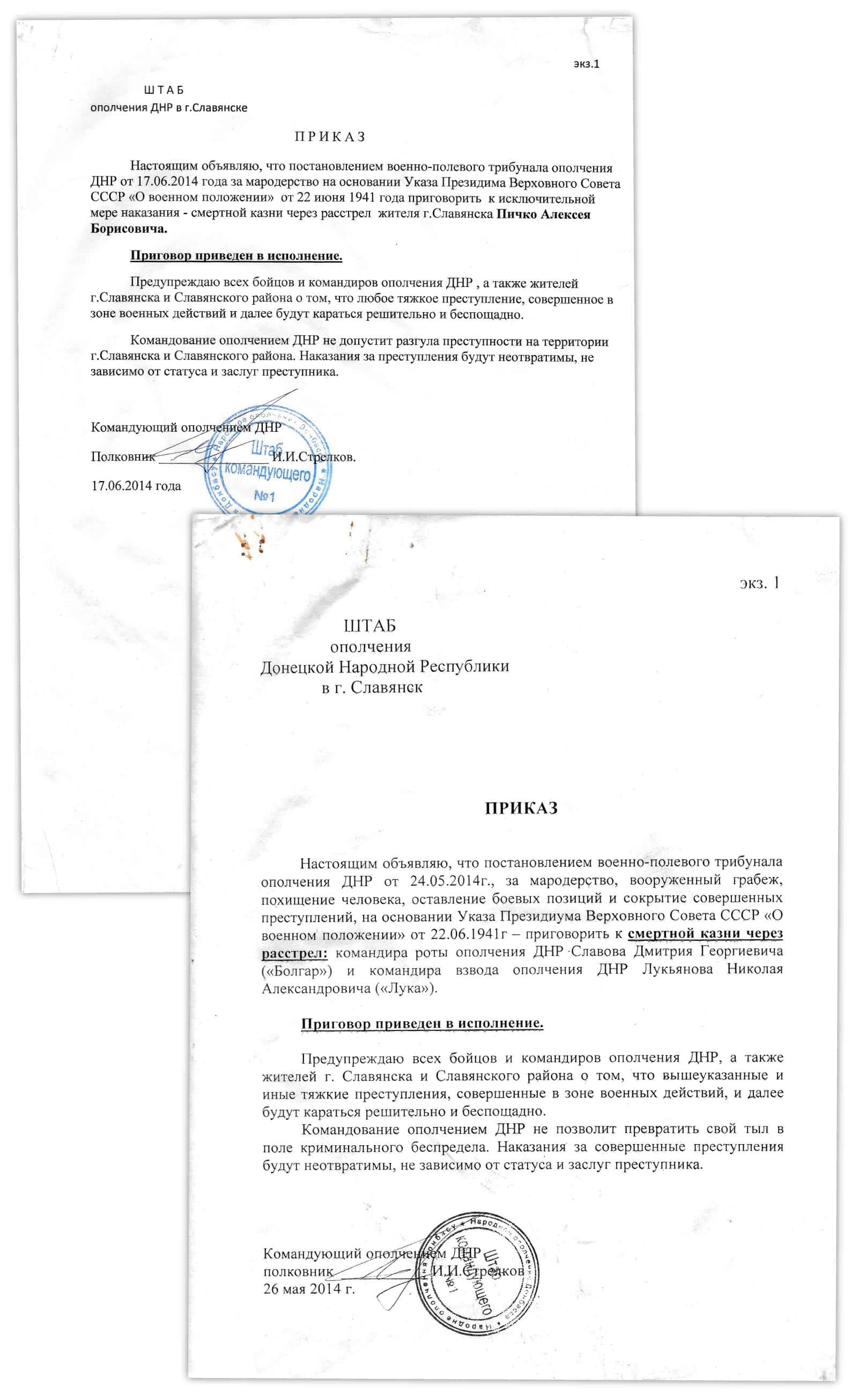

These pages show the not-guilty verdict of a Ukrainian man facing treason charges for shining a flashlight during an artillery exchange with Kyiv’s forces, thus purportedly betraying separatist positions.

- 1 Members of the “tribunal” are identified here only by their call signs.

- 2 The matter had been returned to those investigating for further inquiry.

- 3 The accused man insisted he was not guilty.

- 4 The wife of the accused was questioned in the matter.

- 5/6 Neighbors were questioned as well.

- 7 The “tribunal” found the evidence against the man insufficient.

- 8 While Russia-backed separatists declared independence from Kyiv, the “tribunal” cites Ukraine’s criminal-procedure code in administering their verdict

- 9 The “tribunal” orders the acquitted man to be released immediately.

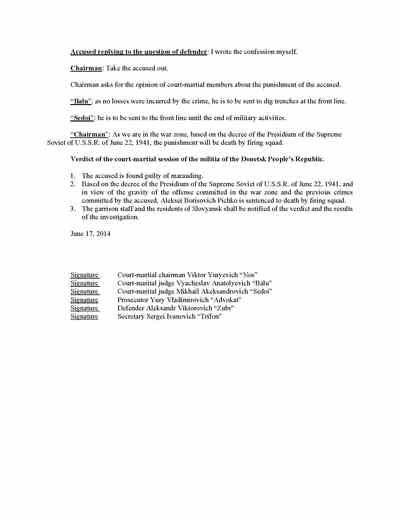

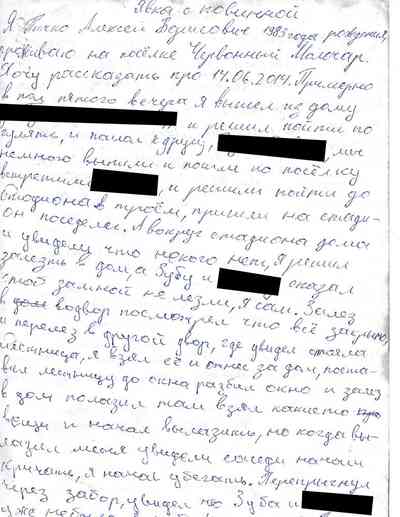

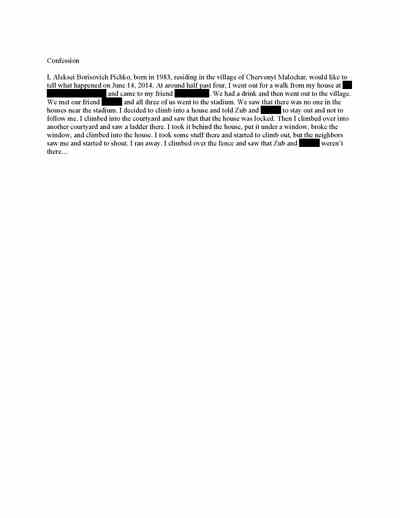

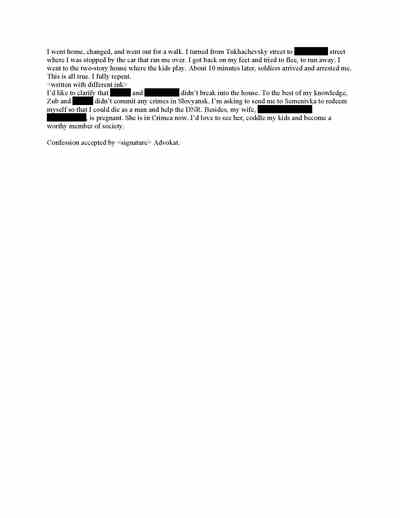

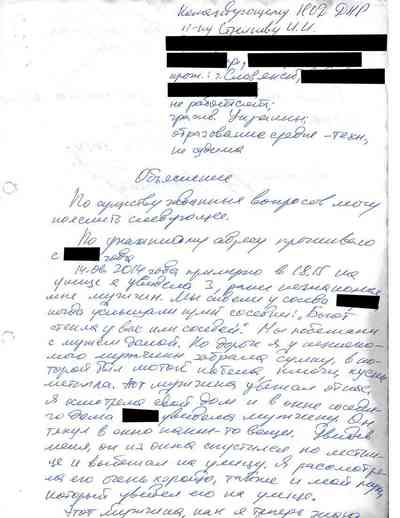

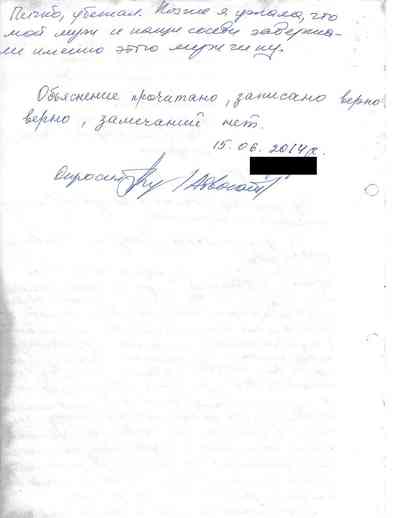

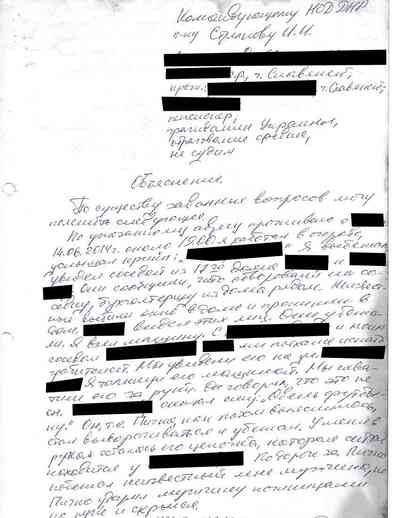

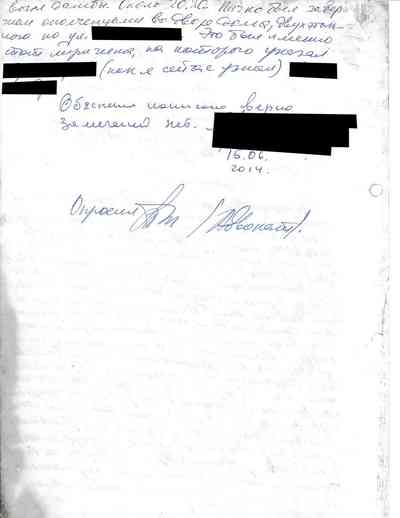

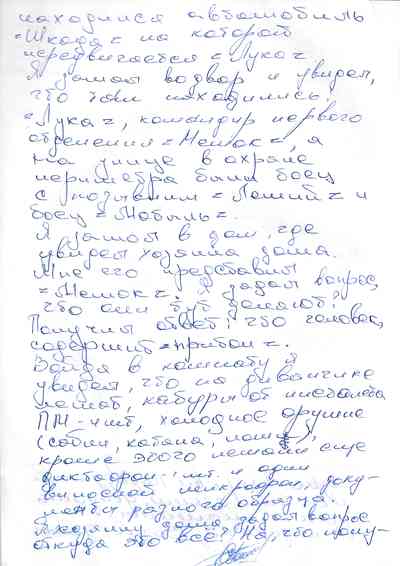

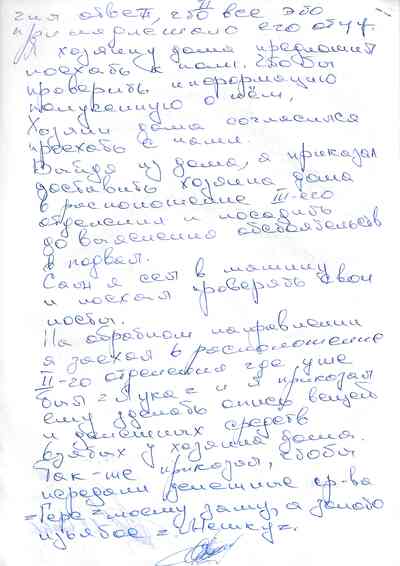

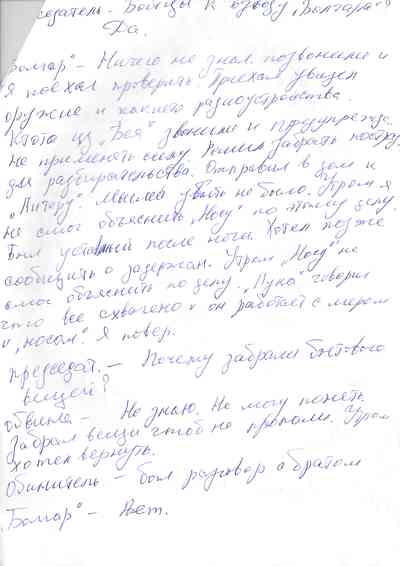

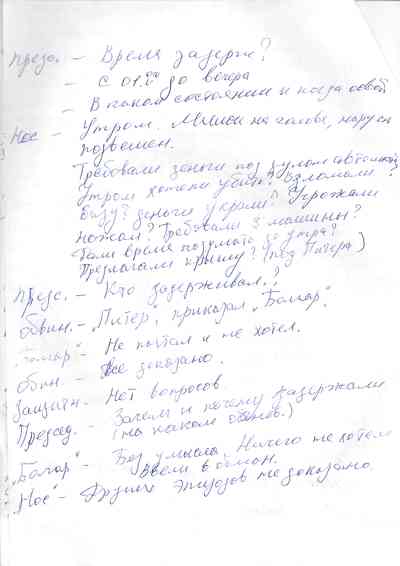

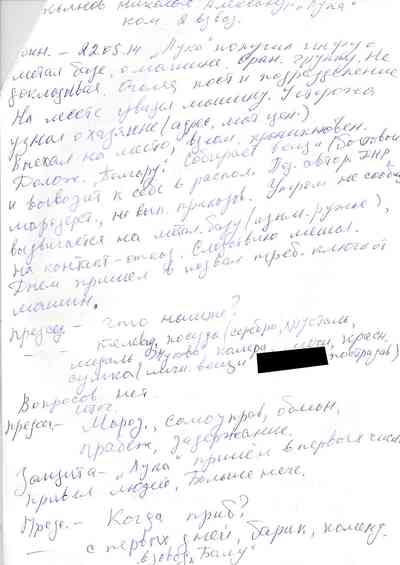

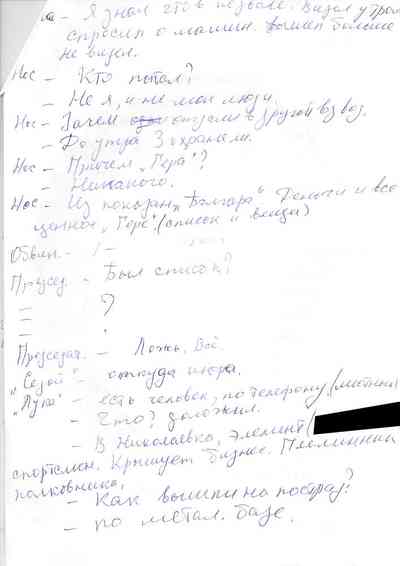

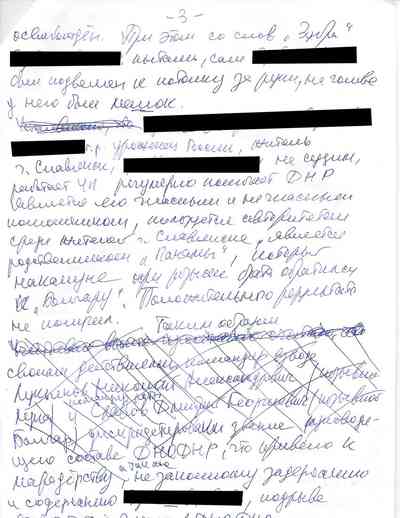

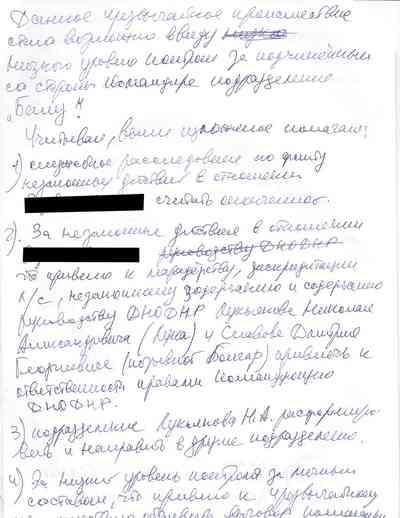

The documents include transcripts of interrogations of the victims, showing what are likely to have been some of their last words.

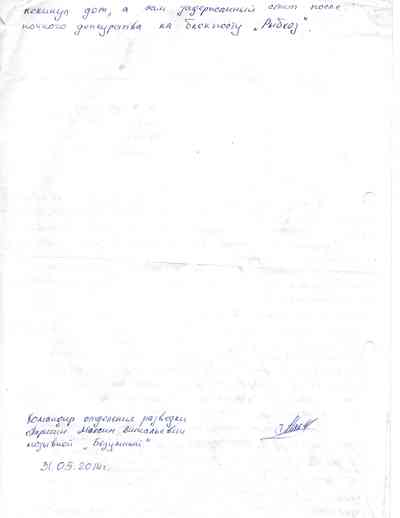

Sometimes Girkin and his men used official letterhead from the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) found inside the building they seized to type up their “tribunal” notes, making for a darkly ironic sight.

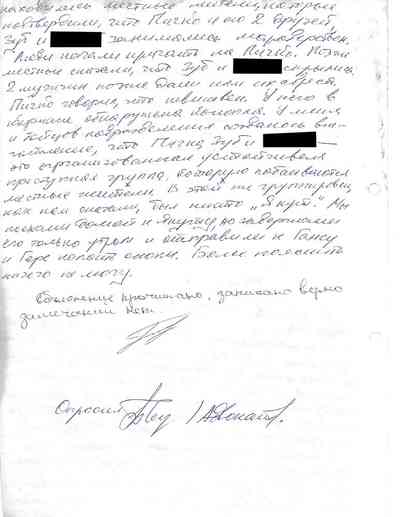

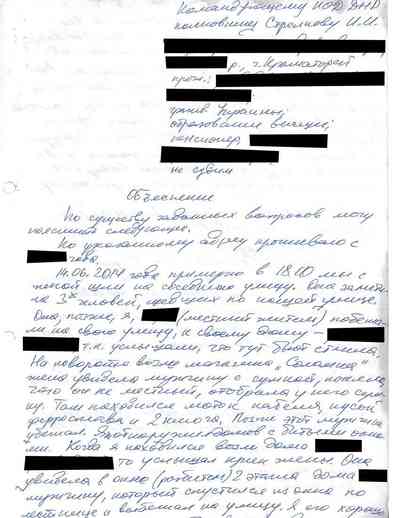

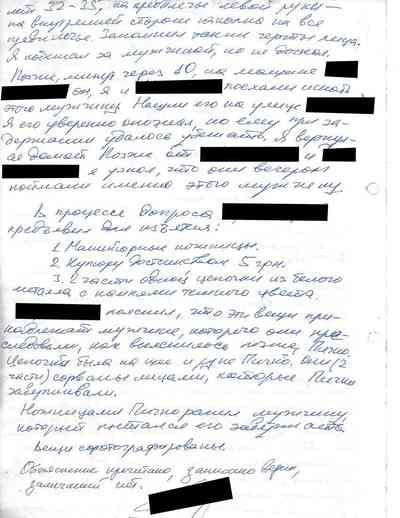

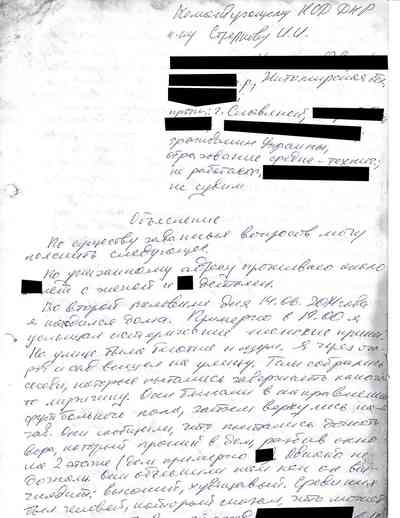

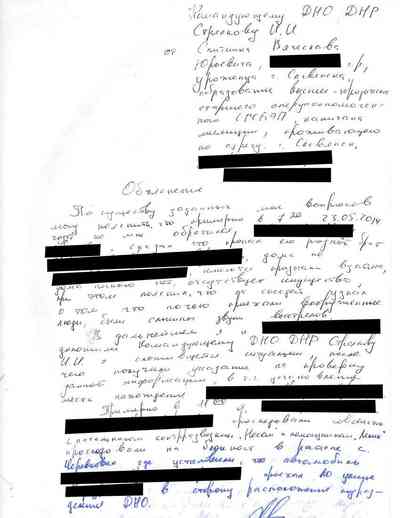

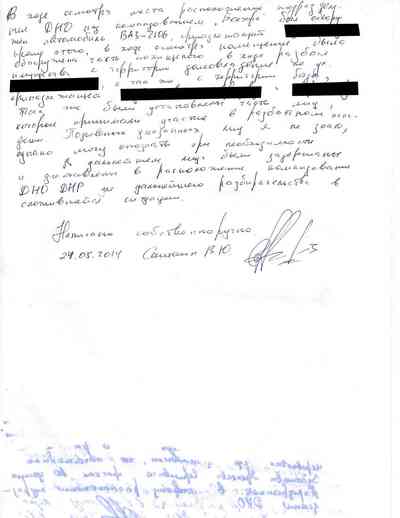

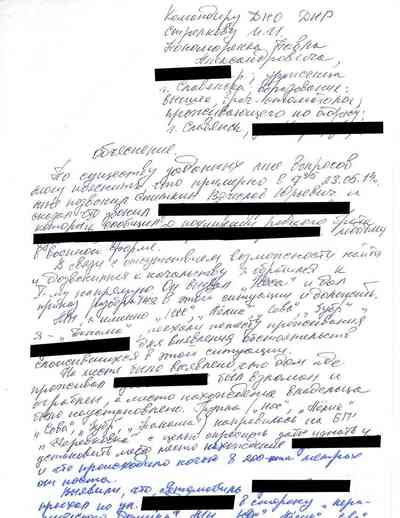

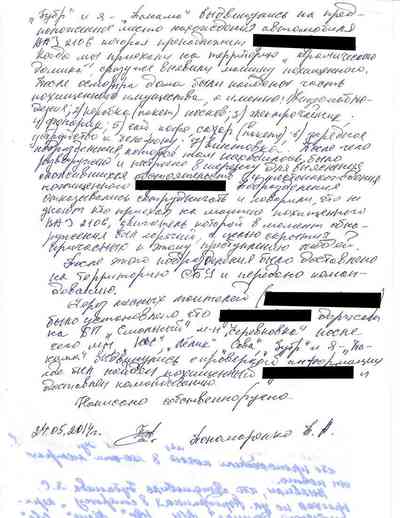

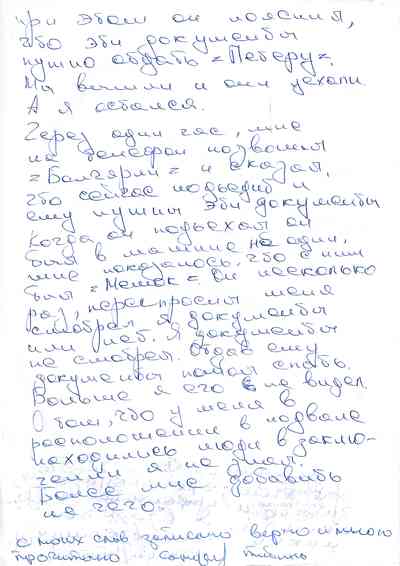

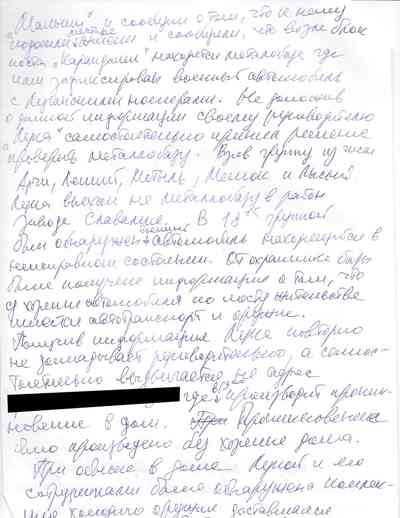

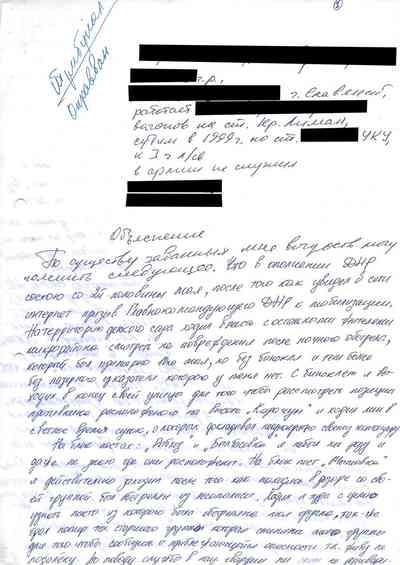

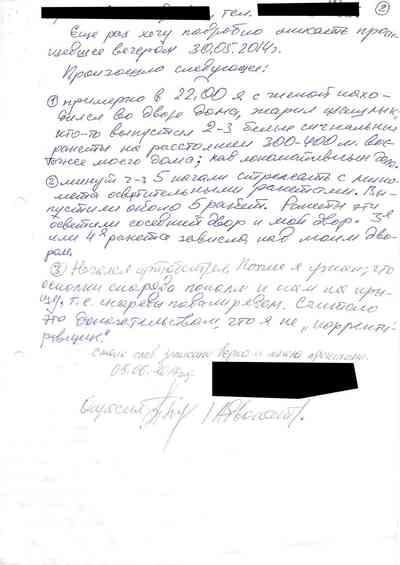

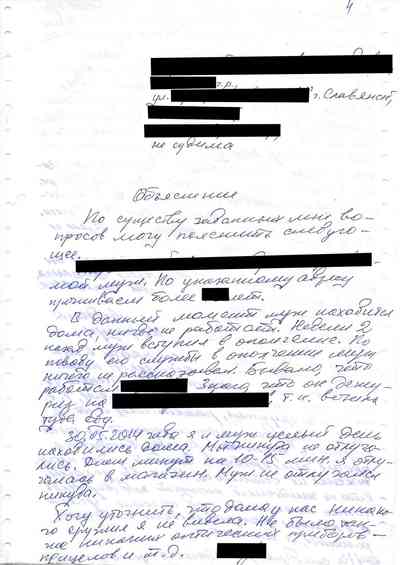

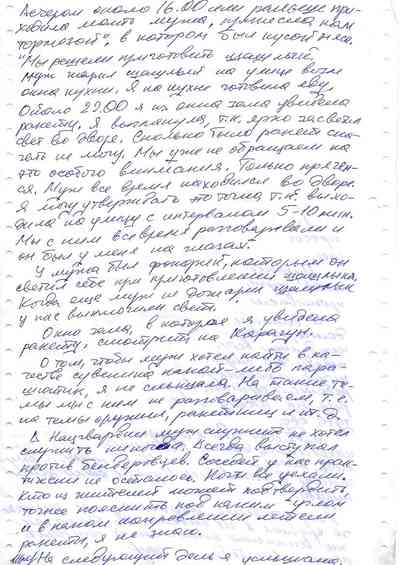

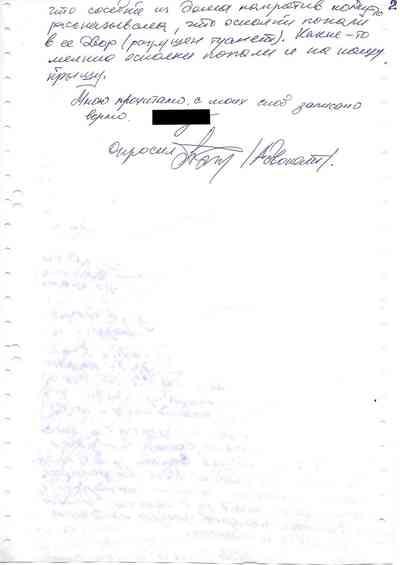

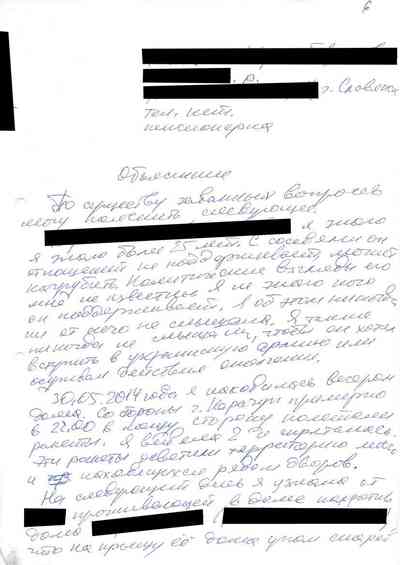

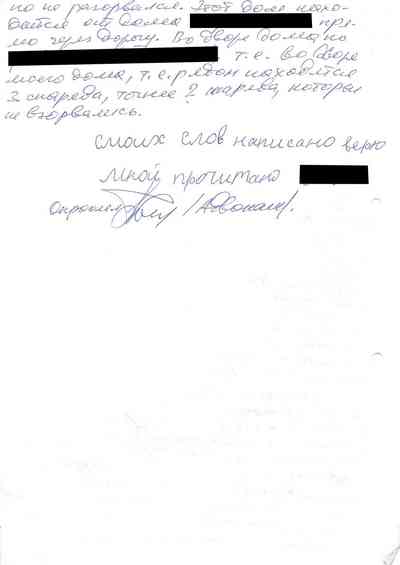

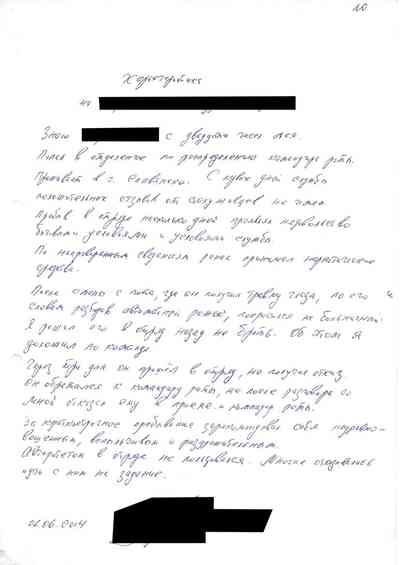

There are also several pages of handwritten “witness testimonies” in the cases, which some Slovyansk residents named in them told RFE/RL they were forced by Girkin’s gunmen to produce. Those residents spoke on the condition that they not be named for fear of repercussions from the Russia-backed separatists or from Ukrainian authorities who could accuse them of harboring separatist sympathies.

RFE/RL redacted information from some of the documents in order to protect civilians who may have provided information to Girkin and his fighters against their will.

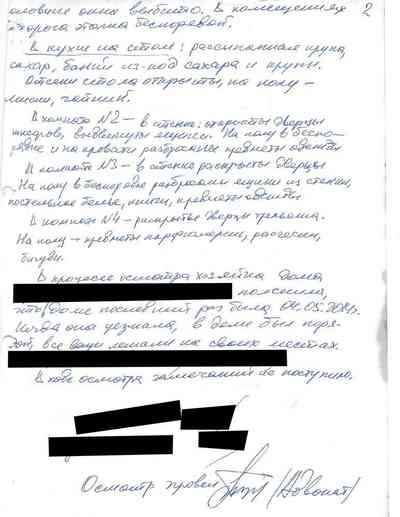

Some of the documents include floor plans of the places where the alleged crimes of Pichko, Lukyanov, and Slavov occurred, showing the lengths to which the “tribunal” went to legitimize its process.

Taken together, the collection provides a window into a particularly harrowing period of time that set a dark tone for the war in eastern Ukraine.

Preview The Documents

Browse and preview the documents by swiping or tapping the arrows.

International and local human rights groups have documented hundreds of cases of arbitrary detentions, torture, and summary killings of combatants and non-combatants on both sides since its outbreak.

The collection of documents also highlights the attempt by the otherwise chaotic and undisciplined Russia-backed separatists to bring a semblance of order to the bedlam and legitimize their armed takeover of Ukrainian territory and declarations of independence.

“The victims were blindfolded and foil was put on their heads prior to the execution (...) They were executed by a shot to the back of their heads fired from automatic guns.”

The authenticity of the documents and the accuracy of the information within them has been verified by the reporters who recovered them, journalists at RFE/RL, former Slovyansk city officials, and several of the people described in the documents.

What is not included in the documents are the names of the individuals who made up the firing squad -- referred to as the “garrison” -- that shot Pichko, Lukyanov, and Slavov. A source with knowledge of the “garrison” members, speaking to RFE/RL on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals, described them as merely “foot soldiers.”

But some details about the firing squad were given in testimony provided for a 2015 report on potential war crimes in eastern Ukraine that was commissioned by Malgorzata Gosiewska, deputy speaker of Poland’s lower house of parliament. According to one former detainee with knowledge of the “tribunals” and executions in Slovyansk who was cited in Gosiewska’s report, they took place late at night and “the victims were blindfolded and foil was put on their heads prior to the execution (...) They were executed by a shot to the back of their heads fired from automatic guns.”

The Fall And Occupation Of Slovyansk

Slovyansk’s transformation from a sleepy city of roughly 115,000 residents nestled amid a group of small lakes on the steppe of the Donetsk region into a hellish war zone began in April 2014, as Ukraine was grappling with the consequences of the Euromaidan uprising that pushed the country’s Moscow-friendly president, Viktor Yanukovych, from power.

Russia’s response in the aftermath of his ouster on February 22, 2014, was swift and fierce. Overnight, Putin ordered Russian troops and special forces units without insignia to be deployed across Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, where they took over government buildings and military installations one by one. Within weeks, they had seized complete control and Moscow organized a Crimea-wide referendum on joining Russia that was condemned by the international community for being held “under the guns” of Russian soldiers.

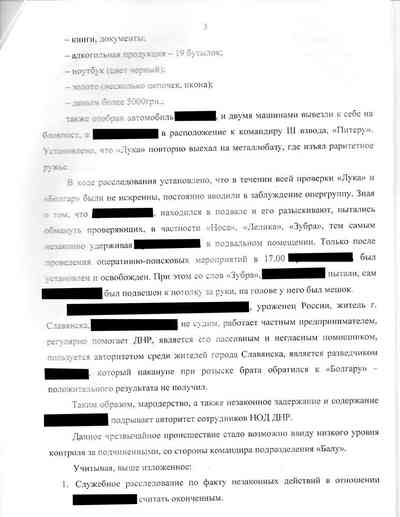

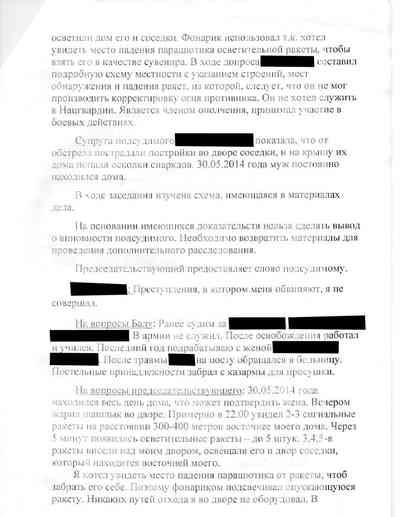

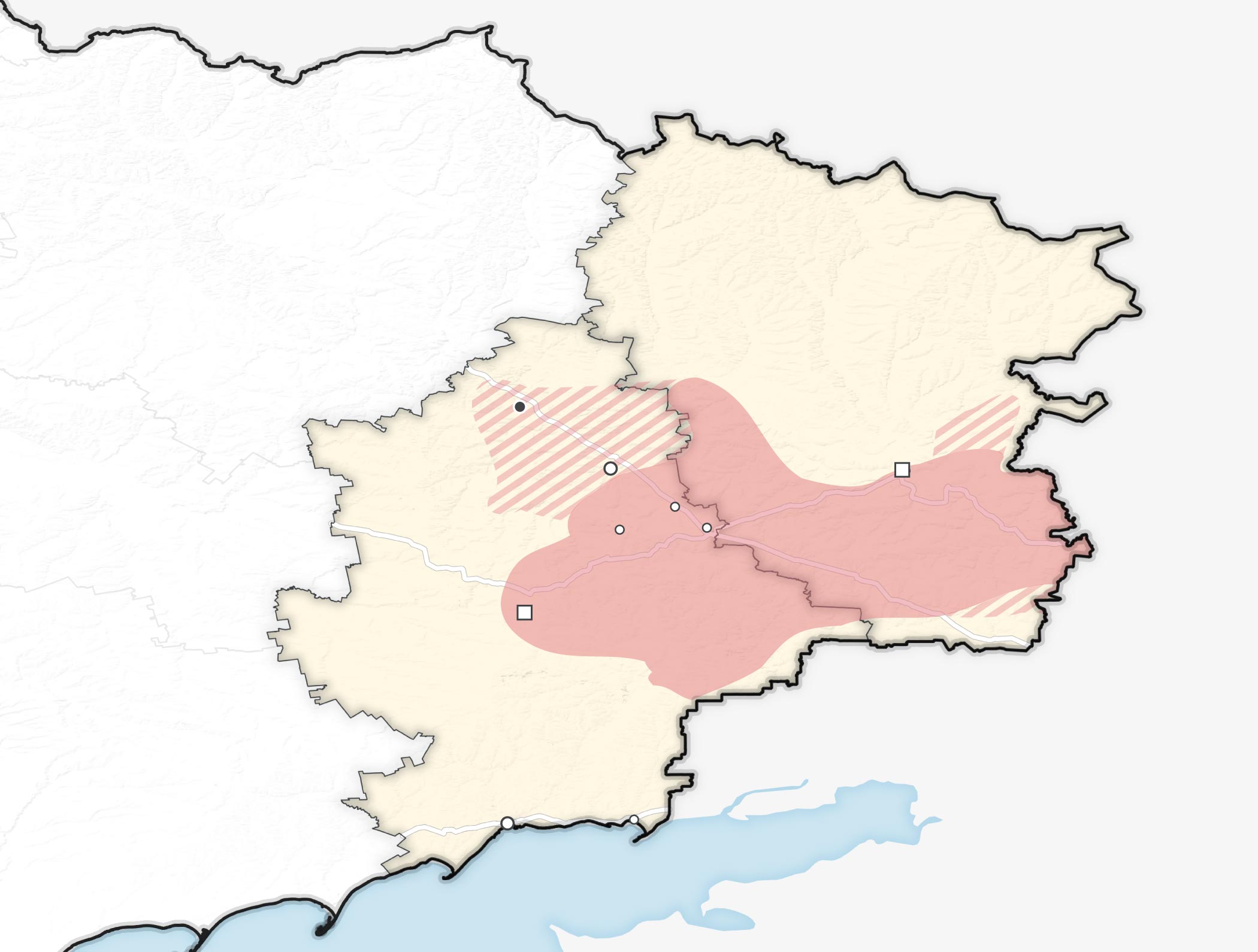

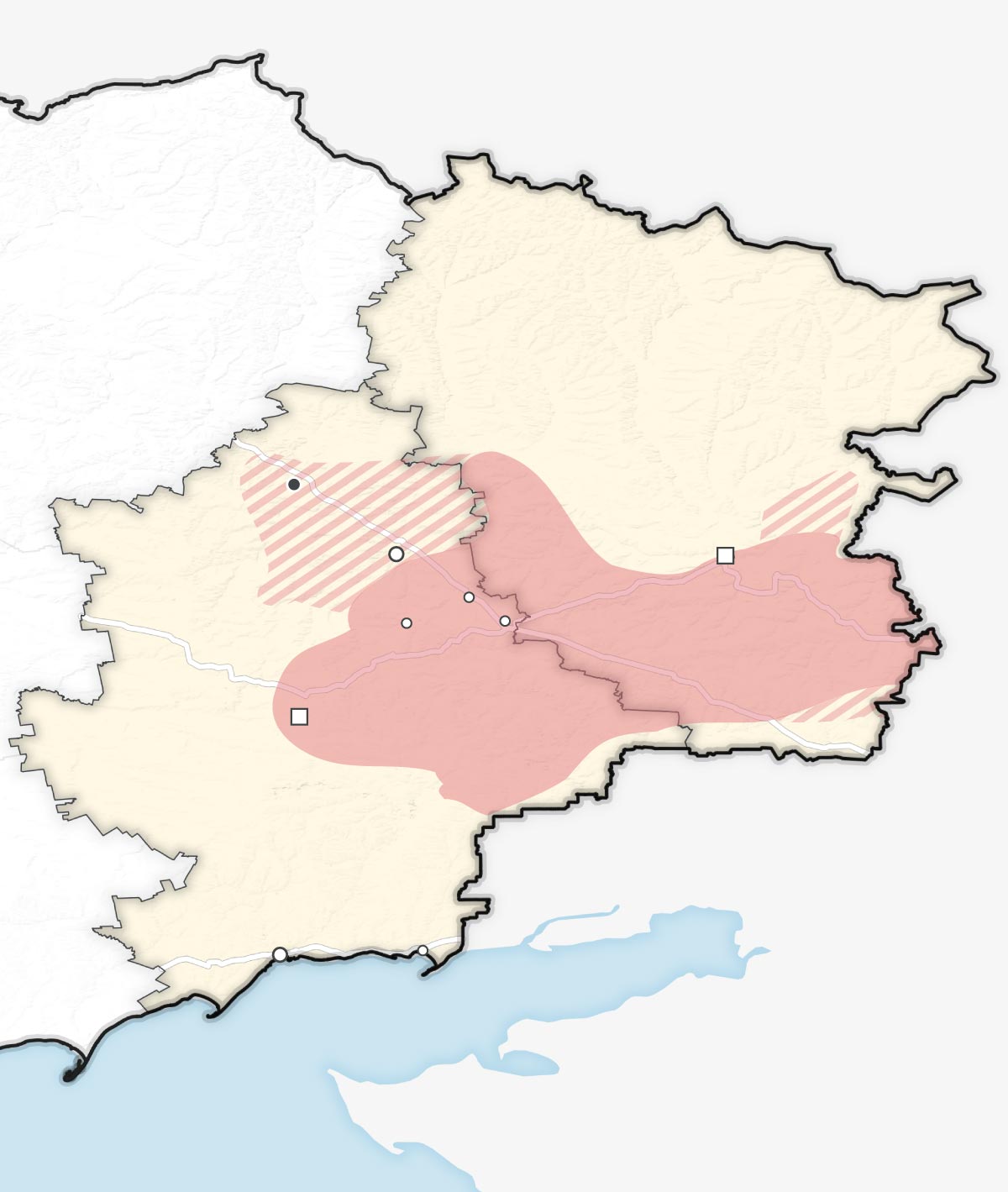

Eastern Ukraine: Summer Of 2014

- Area of Russia-backed separatist control before July 5, 2014.

- Area of control after July 5, 2014.

RUSSIA

LUHANSK OBLAST

Slovyansk

UKRAINE

Artemivsk

Luhansk

Luhanske

Horlivka

Debaltseve

Donetsk

DONETSK OBLAST

Mariupol

Novoazovsk

Azov Sea

RUSSIA

UKRAINE

LUHANSK OBLAST

Slovyansk

Artemivsk

Luhansk

Luhanske

Horlivka

Debaltseve

Donetsk

DONETSK OBLAST

Mariupol

Novoazovsk

Azov Sea

But Russia wasn’t finished. In April, as documents published by Ukrainian hackers and other evidence show, the Kremlin was sending special forces into the predominantly Russian-speaking southern and eastern regions of the country.

Following them were many of the armed men involved in the seizure of Crimea. Among those were Girkin and several men from the so-called Crimean “self-defense” forces, a loose group of local pro-Russian separatists that the Kremlin controlled and used to claim that the takeover of Crimea was a grassroots effort by disgruntled, anti-Kyiv Ukrainians.

The next stop for Girkin and that group was Slovyansk.

In an interview with RFE/RL, Oleksandr Plakhov, director of the local history museum in Slovyansk, recalled the day that Girkin arrived and what life was like under the control of him and his henchmen.

Pointing to pro-Russian separatist flags, photographs, and all sorts of military detritus from the time that make up an exhibition of the ongoing war, Plakhov said Girkin arrived in Slovyansk with 52 fighters around 9 a.m. on April 12, 2014. He recalled the group quickly seizing control of the centrally located city administration building and police department before waltzing into the local state security service building a few blocks away.

They met no resistance, he said.

The local security service officers “opened the doors for them to simply take it,” Plakhov said, adding that much of Slovyansk supported the pro-Russian separatist movement and were displeased with the pro-Western Euromaidan demonstrators who had ousted Yanukovych in February.

Plakhov described Girkin as a mercurial figure, saying he was rarely seen in public and “was never among the people” yet still managed to have his presence felt throughout the city. Most of what local residents learned about Girkin, he said, came from articles published on news sites and chatter among friends and acquaintances on social media.

But he recalled how some people wondered, after a rare public sighting of Girkin, how the scrawny-necked man with a thin mustache and a wooden gun holster at his hip could be the same guy who was described in those articles and social media posts as a ruthless warlord.

That May, he said, the cruelty of Girkin and his henchmen would come into sharper focus.

Plakhov said that’s when residents were punished with forced labor just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, witnessing the movement of armor, arguing with fighters at road checkpoints, or being caught outside their homes after a military curfew that Girkin had imposed.

Violators were often put to work outdoors in the sweltering heat, digging trenches for the soldiers along the front line and erecting barricades on highways and at key intersections near entrances to the city.

The unlucky ones were thrown into the basement of the security service building, where they were interrogated, deprived of food and water, tortured and crammed into tight, dark spaces without ventilation for days on end.

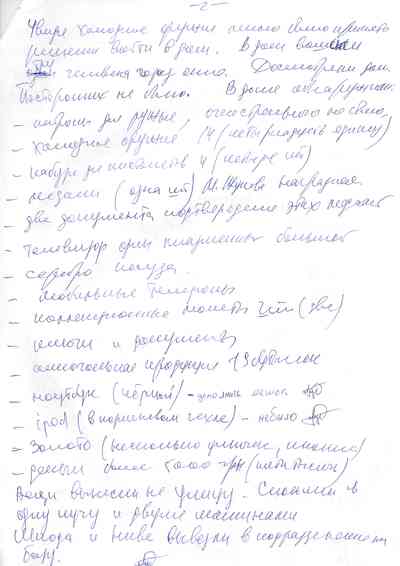

Christopher Miller

His remarks align with what Human Rights Watch and others have reported about forced labor in the Russia-backed areas of Donetsk and Luhansk.

When this reporter visited the basement on July 7, 2014, two days after Girkin and the Russia-backed separatists fled to Donetsk, the scene was grim: Prisoners had left behind bottles that had been cut open to gather drops of water from leaking pipes to drink and bathe with; mattresses infested with bugs where those lucky enough not to be handcuffed or bound by shackles still hanging from the walls had tried to sleep; bowls of spoiled porridge and rotten bits of food discarded in the corners that people had to eat to sustain themselves; and buckets filled with urine and feces.

Yuriy Plastun, a former army major who told RFE/RL that he witnessed Girkin’s arrival as he was withdrawing his monthly pension from a bank ATM, said life under the rule of the Russian commander and his men “was an absolute nightmare.” Residents were “terrified” by Girkin and his henchmen, he said.

And as word spread of executions, people became particularly afraid of having to face the group of men who handed out the harshest punishments of all: the members of the “military tribunals.”

The Executioners

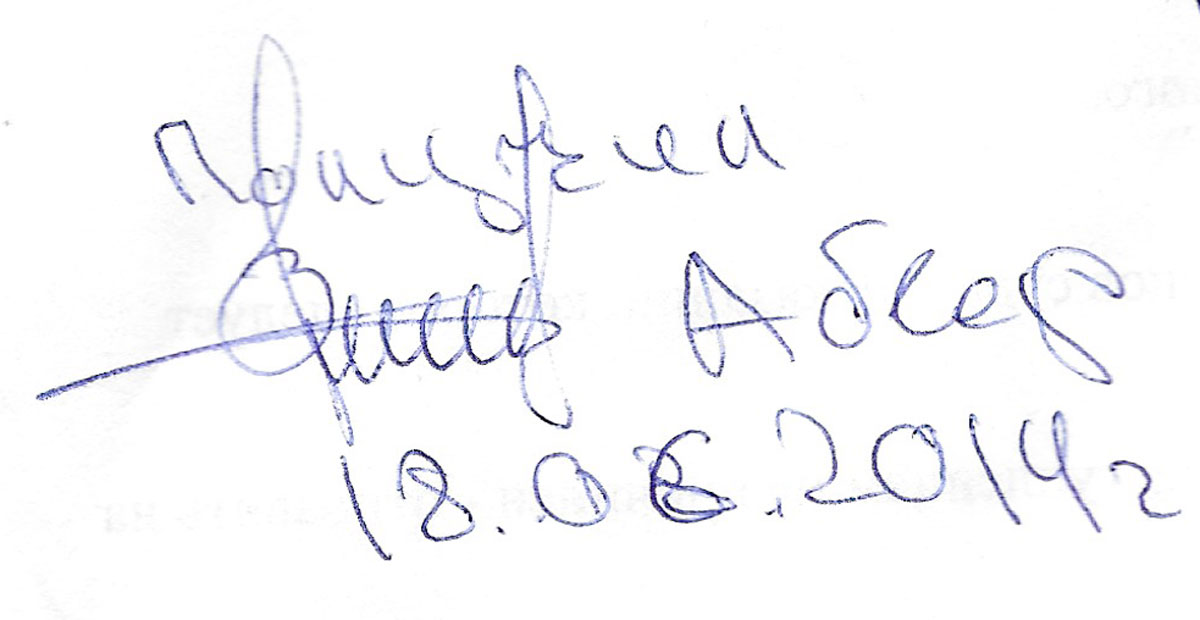

Building on clues inside the documents that include typed and handwritten first names, patronymics, military callsigns, and signatures, RFE/RL has tracked down and identified seven of the nine men who aided Girkin in the “tribunals” and are directly responsible for the executions of Pichko, Lukyanov, and Slavov.

Including Girkin, they are:

- Igor Vsevolodovich Girkin

- a.k.a. “Igor Ivanovich Strelkov”

- Age: 49

- Citizenship: Russian

- Location: Moscow

Girkin is a self-professed former Federal Security Service (FSB) officer and monarchist with a penchant for war reenactments and a fondness for online military history forums that stretches back to his days at the Moscow State Institute for History and Archives. Before the war in eastern Ukraine, he fought in the 1990s conflicts in Transdniester, Chechnya, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But it was his role in Russia’s seizure of Crimea and its military operations in eastern Ukraine that earned him a name among Russian nationalists and pro-Russian militants who flocked to the war, and a notorious reputation in Kyiv and the West for being violent and unforgiving.

Girkin established the “military tribunals” in May 2014, as fighting in and around Slovyansk escalated and, as he has described it in interviews with Russian media, “to bring order” to the city.

He served as chairman in the case of Lukyanov and Slavov, and he signed off on documents that confirmed the death sentences of Lukyanov, Slavov, and Pichko had been carried out. In the case of the latter two men, he signed both his adopted name, Igor Ivanovich Strelkov, as well as his birth name, Igor Vsevolodovich Girkin, on the “tribunal” document.

In confirming the deaths of all three men in typed memos, Girkin warned all soldiers and commanders of the Russia-backed militia as well as residents of Slovyansk and surrounding areas that “grave crimes committed in the war zone will be punished without hesitation or mercy.”

He would “not allow crime to run rampant” in Slovyansk and see it “turn into a realm of uncontrolled crime,” he added. “Punishment for such crimes will be inevitable regardless of the rank and merit of the culprit.”

After Girkin retreated with his men to Donetsk, he became the so-called “defense minister” for the area of Donetsk region under Russia-backed separatist control. But he didn’t last long in the role. In August 2014, as he grew increasingly aggressive, Strelkov said the Kremlin ordered him to return to Moscow.

Girkin has remained in the Russian capital ever since, dabbling in politics and speaking to groups of mostly disaffected Russian “veterans” who fought in eastern Ukraine.

He has been hit with sanctions by the United States and Canada for his role in eastern Ukraine and is currently being tried in absentia in the Netherlands for his alleged role in the downing of flight MH17.

Reached by phone in Moscow, Girkin told RFE/RL, “I have no desire to communicate with you,” and provided no other comment.

- Viktor Yuriyevich Anosov

- a.k.a. “Nose” (Nos)

- Age: 54

- Citizenship: Ukrainian, Russian

- Location: Simferopol, Ukraine

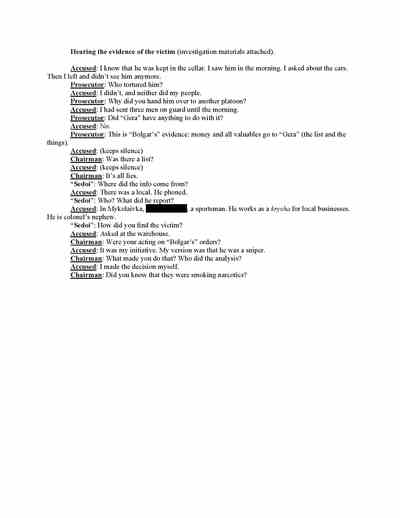

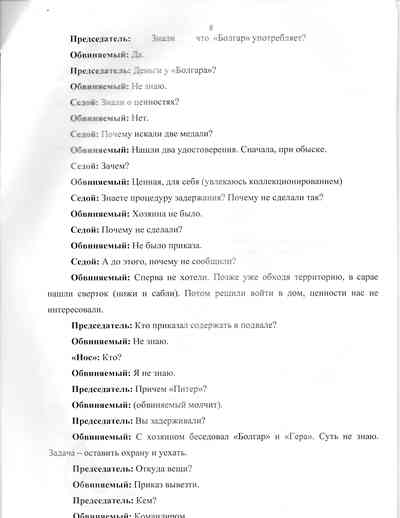

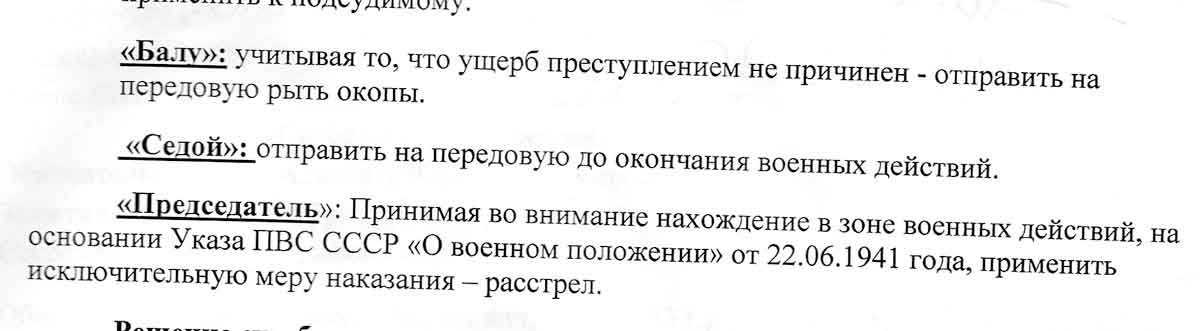

Anosov, a hulking bald man with a nom de guerre reflecting both his surname and a prominent facial feature, was Girkin’s head of “military police.” He served as chairman of the “tribunals” that condemned Pichko and the man in the third case who was acquitted of treason charges, and he was deputy chairman in the case of Lukyanov and Slavov.

In Pichko’s case, Anosov is the one who ultimately decided to sentence him to death, as evidenced by the exchange documented in the “tribunal” transcript.

According to the transcript, Anosov asks two men designated as “judges” for their sentencing recommendations after Pichko is found guilty. One is recorded as saying that “as no losses were incurred by the crime, he is to be sent to dig trenches at the frontline.” The other suggests “he is to be sent to the frontline until the end of military activities.”

But Anosov, acting as chairman of the “tribunal,” overrides their recommendations, saying, “As we are in a war zone, based on the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R. of June 22, 1941, the punishment will be death by firing squad.”

Anosov was a commander of a Donetsk separatist military unit and a leader of the so-called Crimea “self-defense” forces that worked in tandem with Russian special forces to seize control of the peninsula.

A darling of Russia’s state-run and pro-Kremlin media, he regularly spoke to Russian journalists covering the war and posed arm-in-arm with them.

Anosov has been highly active on Russian social media, posting photographs of his heyday in eastern Ukraine. Among the hundreds of photographs are several of Anosov posing in Moscow with Surkov, the longtime Putin aide responsible for the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy at the time. The two are seen together during meetings of a group called the Union of Donbass Volunteers, which is headed by Aleksandr Borodai, the Russian man who served as the Donetsk separatists’ first so-called “prime minister.”

Anosov also appears to be close to Borodai, who is seen in photographs awarding Anosov a medal for his service in Slovyansk and Donetsk.

After leaving the war in eastern Ukraine, Anosov returned to Crimea, where his social media accounts and Russian business filings show him to be the founder and part-owner of a construction company and a brewery in Simferopol, the regional capital.

Canada has imposed sanctions on Anosov for his role in eastern Ukraine.

Attempts to reach Anosov by phone, e-mail, social media, and text message were unsuccessful.

A request for comment to the Union of Donbass Volunteers about Anosov's role in the Slovyansk "tribunals" went unanswered.

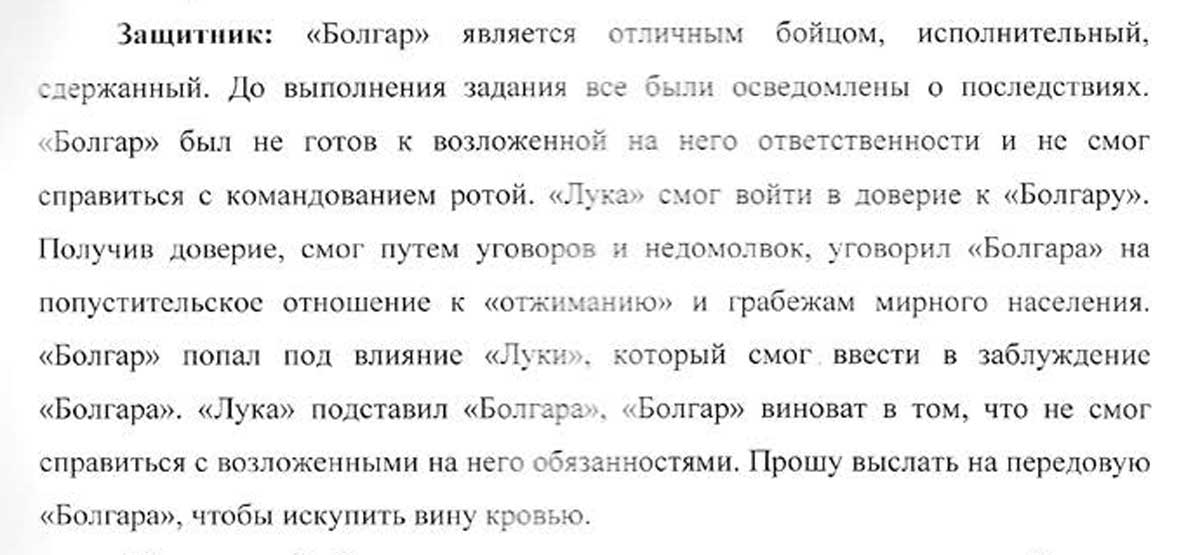

- Vyacheslav Anatolyevich Apraksimov

- a.k.a. “Baloo” (Balu)

- Age: 55

- Citizenship: Ukrainian, Russian

- Location: Simferopol, Ukraine

Apraksimov, a man as large and imposing as his call sign suggests, took up arms with Russia-backed forces, serving as the military commandant for Slovyansk and later as a soldier in the notorious Vostok battalion.

In the “tribunals” that judged Pichko and the man who was acquitted of treason charges, he served as a judge; he acted as the defense for Lukyanov and Slavov.

According to transcripts of Pichko’s “tribunal,” Apraksimov questioned Pichko about the alleged theft at his neighbor’s home. Pichko tried to win him over by saying he “took part in the liberation movement,” a reference to the Russia-backed separatist takeover in eastern Ukraine. “I was at the barricades,” he said.

“I admit my guilt,” Pichko said, asking to be sent to the front line as punishment. “It was the devil’s work,” he concluded, referring to the alleged theft.

In the “tribunal” of Lukyanov and Slavov, Apraksimov argued that Lukyanov was to blame for the crime and that Slavov was a “good soldier” who fell under his comrade’s “bad influence.”

Apraksimov was often seen driving around Slovyansk in a jeep-style vehicle that had been stolen from a local resident, according to an RFE/RL source in the city. He has also appeared in photographs riding atop an armored personnel carrier with other gunmen.

Canada has imposed sanctions on Apraksimov for his role in the war in eastern Ukraine.

Reached on social media, a person identifying himself as his brother said that Apraksimov had suffered a stroke in 2018 and is unable to recount the events of 2014.

- Mikhail Alexandrovich Nikolayev

- a.k.a. “Grey-Hair” (Sedoi)

- Age: 42

- Citizenship: Ukrainian

- Location: Donetsk, Ukraine

Nikolayev, a dour man and one of the Donetsk militants’ most decorated military figures, served as a judge in the all three “tribunals” outlined in the documents.

Serving as a militia leader in Slovyansk and a commander of the “7th Motorized Rifle Brigade” of the Russia-backed forces in Donetsk, which fought in some of the heaviest and most decisive battles of the war, including those at the Donetsk airport and Debaltseve in January and February 2015, Nikolayev quickly rose to become a “colonel” in the militants’ ranks, according to accounts cited in an article about him in a journal published by a university in separatist-held Donetsk..

As of February 2020, he was a senior member of the Russia-backed forces’ military leadership in Donetsk and the director of its department for patriotic education and veterans support. An aide to Nikolayev patched RFE/RL through to his office phone, confirming that he remains in the position, but he was in a meeting and could not answer. In a second call, the aide refused to connect RFE/RL with Nikolayev and instead recommended sending a request for an interview written on company letterhead via snail mail. An earlier e-mailed request went unanswered.

Nikolayev is known to appear from time to time at public events in Donetsk, including a December 2019 children’s function where he reviewed projects created to show why kids “love the motherland” – a reference to Russia.

- Yury Vladimirovich (surname unknown)

- a.k.a. “Lawyer” (Advokat)

- Age: Unknown

- Citizenship: Unknown

- Location: Unknown

Little is known about the man who goes by the nom de guerre “Advokat,” other than that he served as the prosecutor in the “tribunal” that condemned Pichko and on the defense for the man who was acquitted of treason charges.

He argued strongly for Pichko to be convicted, according to the “tribunal” transcripts, saying that he must “be held liable for marauding with all the rigor of martial law.”

RFE/RL followed several leads to track down the identity and whereabouts of “Advokat” without much success. But former detainees who met and spoke with him painted a rough sketch of the man. They said he was of short to average height, around 50 years old, and around 70 kilograms.

They told RFE/RL that he appeared to be involved in the legal sector in some capacity, possibly in Donetsk, and did not seem to have a professional military or security background.

According to an internal report by the Ukrainian Interior Ministry on police officers in Slovyansk who collaborated with Girkin’s forces, “Advokat” was responsible for monitoring intelligence and conducting investigations. The document states that he reported to a superior named Gleb Sidich, as well as to a separatist fighter named Sergei Zdrylyuk, who signed Pichko’s death sentence.

A former detainee of Girkin’s men in Slovyansk confirmed that “Advokat” reported to Sidich, who is currently wanted by Ukrainian authorities. Sidich and his family have since relocated to the Russian city of Nizhny Novgorod, where he has worked in the arms industry and been active in a local Russian Orthodox church.

Reached by telephone, Sidich told RFE/RL that during the siege of Slovyansk by Girkin’s men, he had “defended the homeland” and his “faith.” He declined to comment further or reveal the identity of “Advokat.”

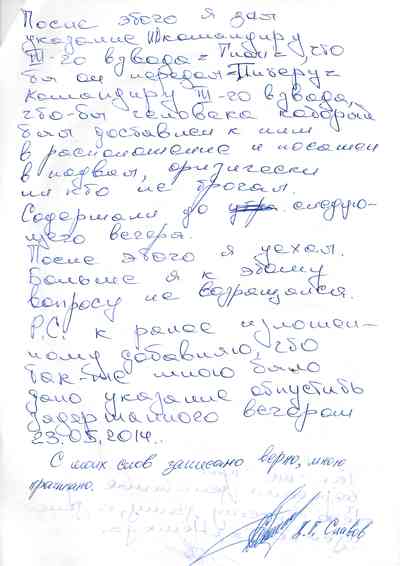

- Aleksandr Viktorovich Zyubanov

- a.k.a. “Bison” (Zubr)

- Age: 45

- Citizenship: Ukrainian, possibly Russian

- Location: Unknown

Zyubanov served as defender for Pichko and as “tribunal” secretary in the case of the man who was acquitted of treason charges.

He argued on Pichko’s behalf that the civilian’s alleged crime of theft “is a minor offense that cannot be qualified as marauding because marauding is stealing from the soldiers killed or wounded in action done by a military or militia officer.”

Zyubanov, who was involved in hostilities in Slovyansk from the first days of the takeover, asked that Pichko be sent to do manual labor along the front line.

Zyubanov appears in a photograph on one of his social media pages wearing a Ukrainian police uniform, suggesting he worked as an officer before the war. That fits with a resume he posted on a work forum in 2009 that said he graduated from a Ukrainian Interior Ministry law academy and is a qualified lawyer.

Photos of Zyubanov posted on social media in March 2013 -- one year before the siege of Slovyansk -- show him attending a conference for PVC-window dealers in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro, about 200 kilometers west of Slovyansk and Donetsk. His first and last name are visible on his conference badge.

In January 2020, Zyubanov appeared in a video interview in which he courted donations for the reburial of one of his fallen comrades. In the interview, he is identified only by his call sign, “Bison” (Zubr).

Zyubanov could not be reached for comment.

Reached by telephone, an associate of Zyubanov’s said it was not possible to put an RFE/RL reporter in contact with him. A follow-up inquiry via messenger asking about Zyubanov’s role in the execution of Pichko went unanswered, though the associate read the message.

- Sergei Ivanovich Trifonov

- a.k.a. “Trifon” (Trifon)

- Age: Unknown

- Citizenship: Ukrainian, Russian

- Location: Crimea or Donetsk region, Ukraine

Trifonov, a big-talking smallish man, boasted in a two-part interview for pro-Russian separatist media that he was part of the so-called “self-defense” forces that aided the Kremlin in its seizure of Crimea. Specifically, Trifonov has said that he helped take over the Simferopol airport to prevent Ukrainian law enforcement from flying in.

Trifonov said he followed Strelkov to Slovyansk. There, the documents recovered from Strelkov’s headquarters show, Trifonov acted as “tribunal” secretary in the Pichko case and prosecutor in the “trial” of Lukyanov and Slavov. He was also the prosecutor in the case of the man acquitted of treason.

In the February interview under the byline of a deputy spokesman for the Russia-backed separatists in Donetsk, Trifonov described how Girkin’s men seized key facilities in Slovyansk, including SBU and police buildings.

Trifonov said that in Slovyansk he operated under a military counterintelligence group led by Sergei Zdrylyuk, the separatist fighter with the call sign “Abwehr” who signed Pichko’s execution order.

The interview includes a photograph of Trifonov standing Trifonov was also close with Arseny Pavlov, a notoriously violent Russian militant known as Motorola who fought in Slovyansk and Donetsk and was later killed by a bomb in the elevator of his Donetsk apartment building.

An RFE/RL source who encountered Trifonov in Slovyansk in 2014 identified him as the man in the photograph.

In a profanity-laden call with a Russian FSB agent in August 2014 that was intercepted and published by Ukraine’s SBU security service, Trifonov expressed concerns about not being able to escape to Russia as Ukrainian forces were moving in. Panicky, he also said he thought that Russia-backed separatists would lose their territory to pro-Kyiv forces “within a month” and that support from the local population was dwindling.

Reporters were unable to locate Trifonov. RFE/RL has passed along questions to him via the separatist authorities in Donetsk and will update this story if he responds.

- Pavel Aleksandrovich Volovoi

- a.k.a. “Mad Dog” (Besheny)

- Age: 41

- Citizenship: Ukrainian

- Location: Possibly Rostov region, Russia; or Crimea; or Donetsk region, Ukraine

Volovoi, originally from Zhdanivka, eastern Ukraine, served as a commander of a unit within the Russia-backed separatist forces in Slovyansk and acted as “tribunal” secretary in the case of Lukyanov and Slavov. He told Russian media on April 12, 2014, that he was involved in the takeover of the city of Kramatorsk, near Slovyansk.

One of his four social media accounts shows he was an active opponent of the 2013-14 Euromaidan uprising and supported anti-Kyiv protests in Donetsk.

Several posts also give insight into his sense of humor. In three entries from January 16, 2014, he reposted memes that read: "I had a certificate from a psychiatrist that I was healthy, but I ate it;” “People were created so that cats had someone to live with”; and “I don’t understand why the bulk of the crimes are committed at night, because you mostly want to kill in the morning.”

A school essay titled “My Neighbor, a War Hero,” written by a student in Volovoi’s hometown, described him as “a miner by profession” who traded in his mining tools to be a “soldier who carries a machine gun and ammunition in his hands.”

Attempts to reach Volovoi by phone, email, and text message were unsuccessful.

- Sergei Anatolyevich Zdrylyuk

- a.k.a. “Abwehr” (Abver)

- Age: 48

- Citizenship: Ukrainian, Russian

- Location: Simferopol, Ukraine

Zdrylyuk, whose nom de guerre comes from a German Nazi-era military intelligence unit, was a Ukrainian security service official before the war; he was described by Trifonov in an interview as “a retired lieutenant colonel of military counterintelligence [and] a very competent person.”

As part of the so-called “self-defense” forces in Crimea, Zdrylyuk aided Russia in its takeover of the Ukrainian peninsula before joining Girkin and heading east to Slovyansk.

According to the Ukrainian Interior Ministry report on police turncoats in Slavyansk, Zdrylyuk and Gleb Sidich authorized investigations to be conducted by “Advokat,” the participant in Girkin’s Slovyansk “tribunals” whose true identity remains unclear.

The report also states that Zdrylyuk and Sidich, who declined to comment in detail on his time in Slovyansk, gave orders to Zyubanov to carry out interrogations of detainees that involved torture. They also ordered executions to be carried out by a fellow separatist fighter using the call sign “Beria,” (see below) the report alleges.

One detainee held by Girkin’s forces in Slovyansk told RFE/RL that Zdrylyuk served as the de facto chief of the separatist "police" there.

In Slovyansk, and later in Donetsk, Zdrylyuk served as Girkin’s deputy in command and led three military units in the nearby cities of Kostyantynivka, Druzhkivka, and Horlivka.

He signed off on the death sentence the “tribunal” handed down to Pichko.

In 2016, Zdrylyuk was photographed at an event held in Moscow by the Union of Donbass Volunteers that was attended by Surkov and Sergei Dubinsky, a former intelligence chief for Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. Dubinsky and Girkin are among the four individuals charged with murder by international investigators in connection with the downing of MH17.

Ukrainian researchers claim he also served in the Russian FSB, which Zdrylyuk has denied.

Last year, Zdrylyuk ran for a seat in the regional parliament in Russia-controlled Crimea on the ticket of the Communist Party.

Attempts to reach Zdrylyuk by phone, e-mail, and text message were unsuccessful.

- "Beria"

- a.k.a.

- Age: Unknown

- Citizenship: Unknown

- Location: Unknown

Little is known about “Beria” and RFE/RL was unable to establish his true identity. But it is clear from separatist blogs, media reports, interviews with former prisoners in Slovyansk, reports from human rights groups, and the documents that he was a senior militant who participated in the extrajudicial detentions and physical abuses of prisoners and signed off on the death sentence of Pichko.

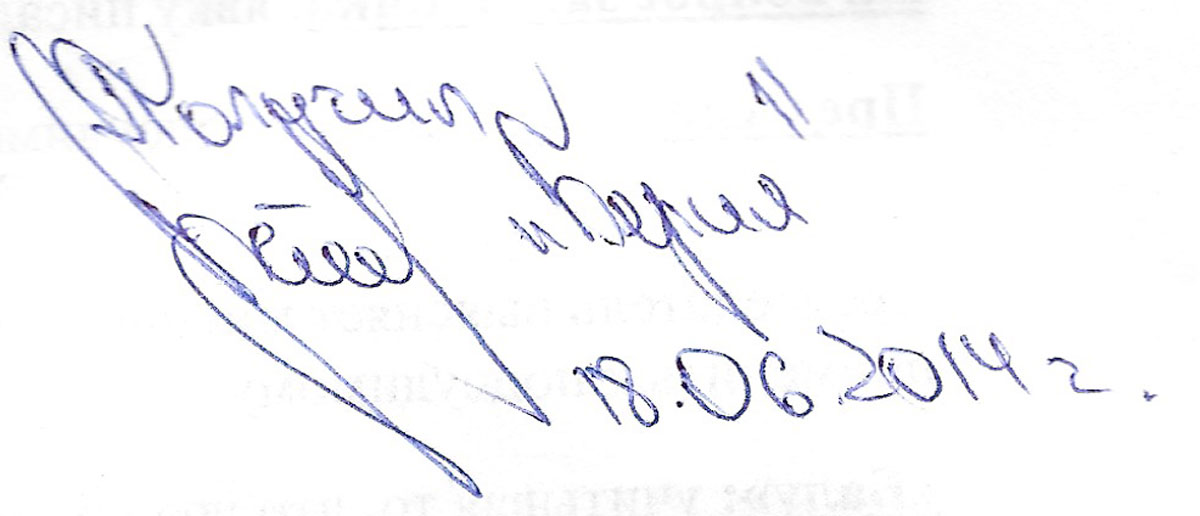

The “Beria” signature is seen on the back of the last page of the transcript of Pichko’s “tribunal” beside Zdrylyuk’s and dated June 18, 2014.

And according to an RFE/RL source in Slovyansk who once met him, and spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals, “Beria” was one of the men in charge of dealing with detainees in the jail run by the Russia-backed forces in Slovyansk.

This account is supported by a Belarusian woman who said in an interview in 2019 that when she first arrived in Slovyansk in 2014 and tried to join the Russia-backed militants she was beaten and imprisoned by “Beria“ -- whose nickname apparently comes from Stalin’s sadistic secret police chief -- and others in the jail where he worked.

In a report compiled by the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, a former detainee who had a run-in with “Beria” in the Slovyansk jail said, “Beria was the chief there, everyone called him Roma,” a diminutive of the name Roman. “It was said that he was a cop from Volnovakha,” a city south of Donetsk, the former detainee added.

Another report by human rights workers accused Beria of “cruel treatment and/or outrages upon personal dignity, [and] arbitrary detention.”

He could not be reached for comment.

Three More Executions; Two Survivors

At least three other men not included in the recovered documents are believed to have been executed on Girkin’s orders, separately from the “tribunal” cases.

In May 2020, Strelkov said in an interview with Ukrainian journalist Dmytro Gordon that in April 2014, he ordered the executions of Volodymyr Rybak, 42, a city council member in the city of Horlivka who tried to replace a separatist flag with the Ukrainian flag over the council building, and Yuriy Popravka, 19, and Yuriy Dyakovskiy, 25, who were students. Girkin accused the men of being “spies,” “saboteurs,” and “enemies.” Their mutilated bodies washed up in a river days after their disappearances.

Just one man is known to have been tried by the “military tribunal” and acquitted of the charges against him.

The man, whose name RFE/RL has redacted from the documents because he could not be reached for comment, stood accused of treason and faced an intense interrogation. He was ultimately found not guilty and set free.

The man confirmed to this reporter in a phone call in July 2014 that he had been detained and “tried” by the group in Slovyansk but he refused to provide any more details. He could not be reached at numbers belonging to him and his family members for comment for this investigation.

There is also one local Slovyansk man, Denis Trefilov, who was mentioned in a document signed by Girkin that surfaced on social media. The document stated that Trefilov had been executed by firing squad after a “military tribunal” found him guilty of armed robbery in Donetsk. The document is dated July 17, 2014, and says the death sentence had been carried out.

But RFE/RL has confirmed that Trefilov is in fact alive and living in Slovyansk. He keeps an active social media account with a working mobile number. Reached by phone, Trefilov confirmed he was the man named in the document but said that he was not shot to death. He declined to discuss his “tribunal” without being paid for his story, but he said he believed he was the “only survivor” of those who were “convicted” in the “tribunals.”

Seeking Justice

Every year on July 5, Slovyansk and neighboring Kramatorsk celebrate the expulsion of Russia-backed forces from the cities and their release from Girkin’s grip. This year, because of the risk of the coronavirus, celebrations were fewer and smaller. Prime Minister Denis Shmyhal, donning a face mask, visited the cities and met with locals and members of law enforcement agencies, while President Volodymyr Zelenskiy joined the group via video conference from Odesa.

“Six years ago, the whole country helped our army and waited for the good news from the east with anxiety in our hearts and prayer in our souls,” Zelenskiy said. “We bow to everyone who returned Slovyansk and Kramatorsk to Ukraine.”

Marking the anniversary, local Slovyansk news site 6262 released a documentary about events six years ago titled 84 Days, the number of days residents endured under the rule of Girkin and the Russia-backed separatists.

Slovyansk residents received a sign weeks earlier that Ukrainian authorities are working to get justice for them and the country.

On June 16, the Prosecutor-General’s Office of Ukraine officially charged Girkin with what it said were war crimes under Ukrainian law for allegedly ordering the torture and murder of Rybak, Popravka, and Dyakovskiy in April 2014.

“These citizens were moved against their will into [the security service building] in the city of Slovyansk, where they were tortured, beaten, stabbed, and [subjected to] other violent actions aimed at inflicting severe physical and moral suffering with the aim of revenge for a pro-Ukrainian position,” the Prosecutor General’s Office said, announcing the charges against Girkin. “On the orders of the suspect, fighters subordinate to him deliberately took the lives of at least three people who were illegally detained and tortured.”

Girkin resides and lives freely in Moscow, and he is unlikely to be apprehended and brought to Kyiv to face trial. Ukraine is also unlikely to get any help from Russia, which does not extradite its citizens, has severely damaged ties with Kyiv due to its aggression in Ukraine, and might be concerned that Girkin possesses damaging information about a war in which the Kremlin, despite ample evidence, has denied direct involvement to this day.

Meanwhile, the report on possible war crimes commissioned by Polish lawmaker Malgorzata Gosiewska in 2015 was submitted to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague for consideration the following year.

Gosiewska told RFE/RL in early July that the court “is still conducting a preliminary examination of the situation in Ukraine.”

“The prosecutor is…preparing for the next phase of the proceedings, i.e. submitting an application for authorization to initiate an investigation,” she said.

The ICC did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Meanwhile, the relatives of the MH17 victims and those of Pichko are holding out hope for some semblance of justice but not holding their breath. A woman identifying herself as Slavov’s mother declined an interview with RFE/RL and described briefly having a strained relationship with her son, who she said she had not seen for at least several weeks before his death. Relatives of Lukyanov were not at their home near Slovyansk when RFE/RL visited. But neighbors took a reporter to his grave nearby. There, a wreath was set against a headstone engraved with Lukyanov’s portrait.

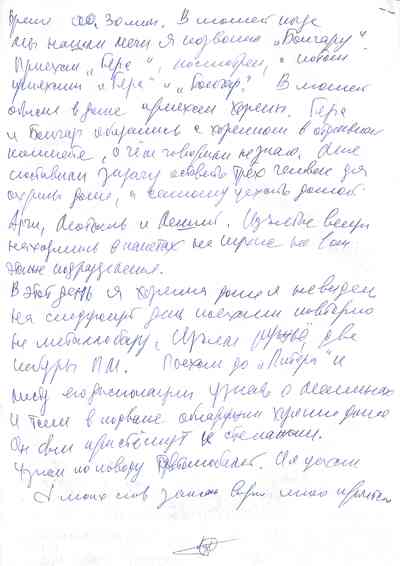

Serhiy Horbatenko

To this day, Pichko’s mother, Maria Pichko, says she can’t understand why her son was shot to death, even if he did steal a few items of clothing. When RFE/RL visited her in 2016, she said she still couldn’t believe her only son was gone even after a DNA test helped to identify his remains, which are now buried in a Slovyansk graveyard and marked with a small cross adorned with a white placard that bears his name. Maria said that when she sets the table for dinner every night, she glances at the front door in hopes that he will walk through it.

She shared family photographs of Oleksiy with RFE/RL during a visit in June and said that she still has not gotten over his death, that her life today is “sad,” and that the road to justice may be a long and disappointing one.

Even if Girkin and the nine others are someday tried, convicted, and sentenced to years behind bars, she said, nothing will bring back her son.

- Additional reporting for this story was contributed by Marek Hajduk, Serhiy Horbatenko, Timur Olevskiy, and Levko Stek

- Editing by Steve Gutterman and Carl Schreck

- Design by Wojtek Grojec

- Translations by Petr Serebrianyi