Beslan. Cemetery, September 2004. A woman at the grave of her granddaughter.

Beslan. Cemetery, September 2004. A scene from Chekhov. Three sisters: Olya, Zaya, Anya.

Beslan. Cemetery, September 2004. A scene from Chekhov. Three sisters: Olya, Zaya, Anya.

Beslan. Cemetery, September 2004. A scene from Chekhov. Three sisters: Olya, Zaya, Anya.

Beslan. Cemetery, September 2004.

Beslan. September 2004. The school after the assault.

Beslan. September 2004. These boys found their mother's name on the list of those seriously injured, together with the name of the hospital where she was sent.

Beslan. September 2004. Irlanda Zampayeva, 7, and Tsezar Khugayev, 13. They both endured the whole seige. They emerged alive but not unscarred. They both had burst eardrums.

Beslan. September 2004. They searched for Kristina and her grandmother, Taira Besholovna, for three weeks and buried them on September 24. The remains of Kristina's mother, Alla, were never identified.

Beslan. September 2006. School No. 1 on the second anniversary of the tragedy.

Beslan. September 2010. School No. 1. Old women cry over their grandchildren on the sixth anniversary of their deaths.

Beslan. September 2010. School No. 1. Old women cry over their grandchildren on the sixth anniversary of their deaths.

Beslan. Cemetery. September 2008. At a schoolmate's grave.

Beslan. Cemetery. September 2008. A grandfather at the grave of his daughter and five grandchildren.

Beslan. Cemetery. September 2008. A grandfather at the grave of his daughter and five grandchildren.

The victims did not manage to force an international investigation of the tragedy.

On September 1, 2004, one of the worst terrorist attacks in Russia's history unfolded at a school in the small North Ossetian town of Beslan. Dozens of armed assailants stormed the school and captured more than 1,100 people -- including more than 700 schoolchildren and relatives and friends who had come for a ceremony marking the first day of the new school year.

The resulting standoff ended 2 1/2 days later, but its resolution was the deadliest episode of the story. A handful of victims had been killed over the initial two days by the attackers, who were linked to an insurgency in neighboring Chechnya. But in the course of a few hours on September 3, several hundred more -- most of them children -- were killed during a chaotic battle as security forces stormed the school with the support of heavy weaponry, including tank fire and grenade launchers.

From the tragedy's outset, authorities had misled about the number of hostages, offering vastly underestimated figures and giving rise to doubts about the official version of events.

However, the official investigation into what became known as the "Beslan massacre" or the "Beslan school seige" ignored any question of responsibility on the part of federal authorities or the local command center for the high price paid for the liberation of Beslan's surviving hostages.

Khasan

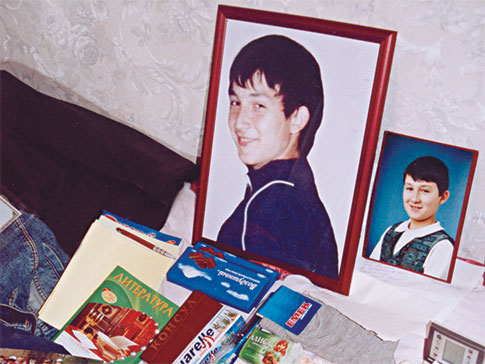

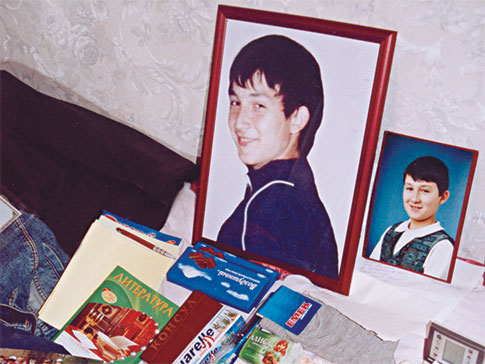

Fourteen-year-old Khasan Rubayev loved physical education most of all. He was an athletic child -- the fastest runner, the highest jumper. Admittedly, he had trouble with other subjects in school, but he planned to make athletics his career and he was sure he'd be a success. His mother and his grandmother had no doubts either, although, as you might expect, they nagged him when he brought home grades in mathematics and literature that were considerably worse than those he got in physical education. When Khasan was taken hostage along with hundreds of other children, his relatives remained sure to the very last that he would get away -- precisely because he was so athletic. Initially, they hoped he'd managed to slip away during the confusion of the first moments of the school's seizure; several other students actually managed to run off and were rescued. Later, they hoped that Khasan would manage to jump unharmed from the school building once the rescue operation began and people braved the crossfire to surge out of the flames. But there would be no such miracle for Khasan. Not even his speedy legs could save him. He perished along with hundreds of others. Since then, his grandmother has set up and lovingly tended a small memorial of photographs next to the sofa where Khasan slept in the apartment he shared with her and his parents. On a bench, his school drawings (Khasan loved to draw), his textbooks, his backpack, and his clothes are carefully laid out. And on the floor, under the bed, are his beloved running shoes.

Gosha

It might seem odd to describe 11-year-old Gosha Tsagaroyev as extremely lucky. But when I visited him at the end of that deadly September, the hole from the bullet that had passed through his body had almost healed over. Looking at him, it was hard to imagine the trauma that Gosha had survived. He looked like any ordinary boy, lying on a couch and playing a game. Only the maturity of the sad, focused expression in his eyes hinted at what he had endured. Gosha had been taken hostage together with his mother and spent the next two days as a captive. Once the assault began on September 3, he had leaped from a window after the second explosion. But his mother had remained in the gymnasium, deafened by the blast. Gosha had stood for a long moment beneath the windows, waiting for his mother. He had only run off after someone standing next to him was shot. Meanwhile, Gosha's mother had come back to her senses and begun looking for her son. The fire had already broken out in the gymnasium and she looked everywhere. Russian soldiers had to forcibly drag her to safety. Gosha's teacher, Marina Bitsoyeva, had told me that Gosha had been an excellent student -- one of the very best. But later that month, there was no hesitation as he responded firmly, "No," when I asked if he wanted to return to school. He hadn't ventured even as far as the street since the tragedy. All he wanted to do was play piano -- which he studied in school -- but his mother wouldn't allow it, asking him to wait at least 40 days from September 3 out of respect for the dead. It wasn't the time for music, she said, particularly since directly below the Tsagaroyevs' apartment was the home of the Alikov family, all of whom had perished.

Kristina and Liza

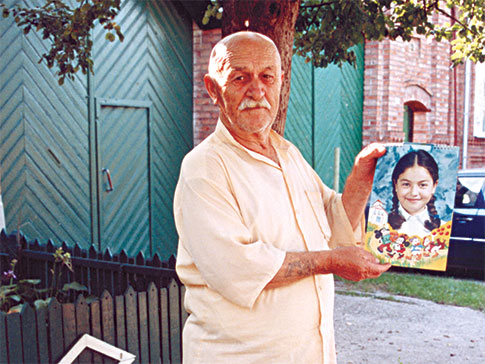

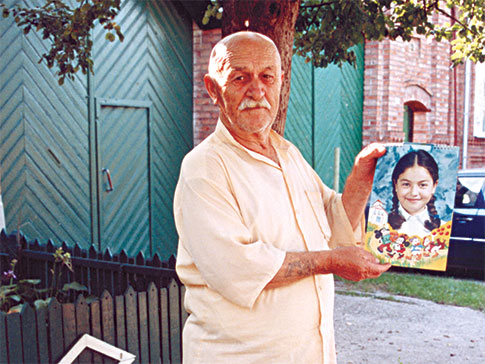

Eleven-year-old Kristina Bekuzarova had been seriously wounded in the September 3 assault. With three pieces of shrapnel lodged near her heart, she had been evacuated to Moscow, where doctors managed to save her life. When I visited her family later that month, her 80-year-old grandfather had begun to recover from the mental shock and proudly showed me a large color photograph of a girl with an irresistible smile. He told me that when Kristina had been pulled from the destroyed gymnasium, she was covered with wounds, and even her ear was torn. But as she was lying on the stretcher holding her wounded ear, the first thing she had said to her grandfather when he ran to her was, "Tell Grandmother that she shouldn't worry, the earrings that she gave me are OK." Later, in the hospital, when visitors were allowed in and she noticed someone with tears in their eyes, Kristina warned them, "If you are going to cry, then don't come anymore." Her confidence, courage, and calm were anything but childlike. But even those qualities cannot provide protection from a stray bullet. Kristina's neighbor and classmate, Liza Tsirikova, had been taken hostage together with her mother and behaved with maturity beyond her years. She hadn't cried or complained. On the first day of the standoff, many hostages had stripped down to their underwear because of the unbearable heat and stuffiness. Liza had carefully folded her uniform and kept it the whole time under her arm along with her slippers. "I won't leave anything for those bad people," she had told her mother. She had died in her mother's arms during the rescue effort when a fragment struck her in the head. Her mother survived, but she recalls nothing after the moment she saw her daughter die. Liza would have turned 8 years old on September 15, 2004. The gifts had been prepared in anticipation of the birthday celebration. There was even a candle in the shape of the numeral 8 ready for her cake. When I went to Liza's house at the end of September to visit her bereaved parents, the gifts were lying in her room, on her little bed. And the candle was there, too, transformed from a birthday candle into a memorial.

Sources: news.bbc.co.uk, commons.wikimedia.org