Tunnel 57

"During the very first days, it was kind of possible but already very dangerous -- people were jumping over the barbed wire, but only a very few. A few days later the East German border guards started to shoot at escapees."

The communist authorities had become so alarmed by the mass exodus of East Germans that they built a wall to stop it, and West German students were on a mission to tunnel in from the other side.

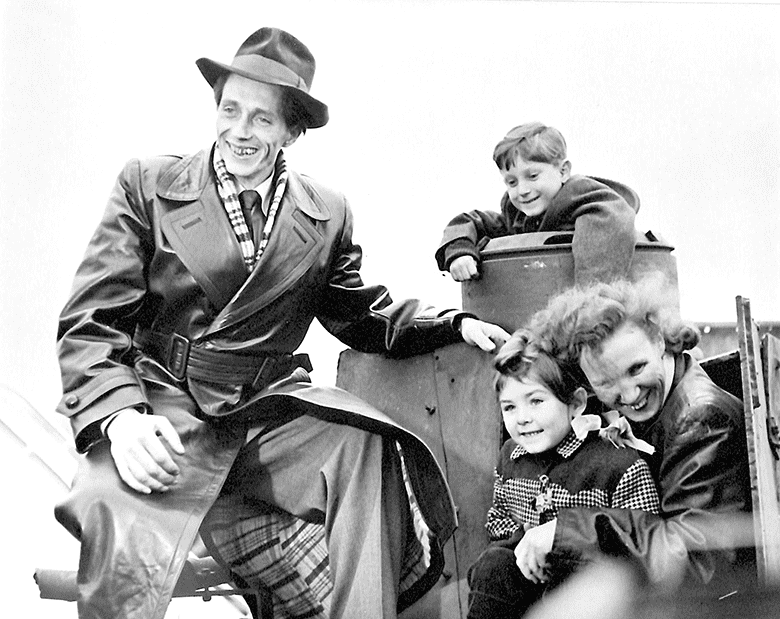

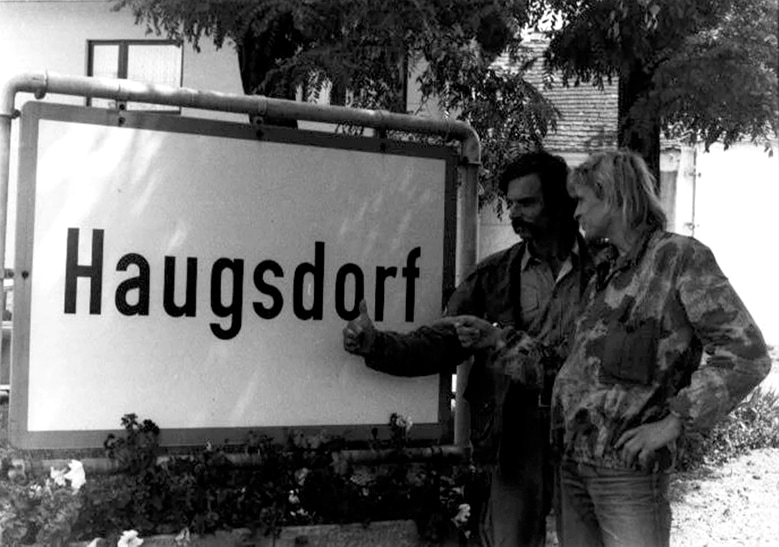

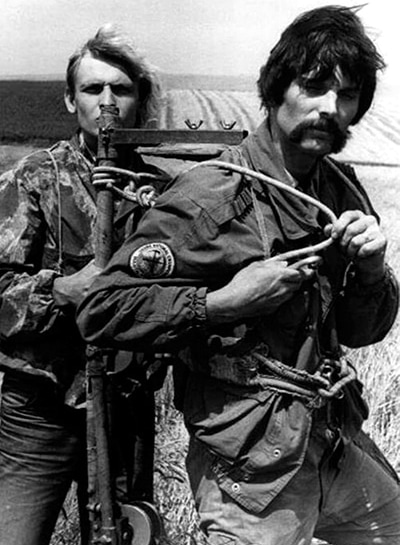

Ralf Kabisch, Joachim Neumann, and about 20 other university students spent much of 1964 digging below a vacant bakery they had rented in the shadow of the Berlin Wall, working two-hour shifts to extract the hard clay handful by handful.

After five months, driven to extract compatriots trapped in East Germany, they had carved a narrow passage 12 meters deep and running 145 meters to the courtyard of an apartment building just behind the Iron Curtain.

And then they hit pay dirt -- ground softened by the spades of wartime Germans who had dug emergency latrines two decades earlier.

"We ended up in shit," Kabisch recalled in a 2014 video interview. "But it was very good luck for us. Was really a blessing in disguise."

"We had set the goal that if all went well, if nothing busted, and nothing unexpected happened, that two meters a day was our goal. If we managed that, it was very, very good.

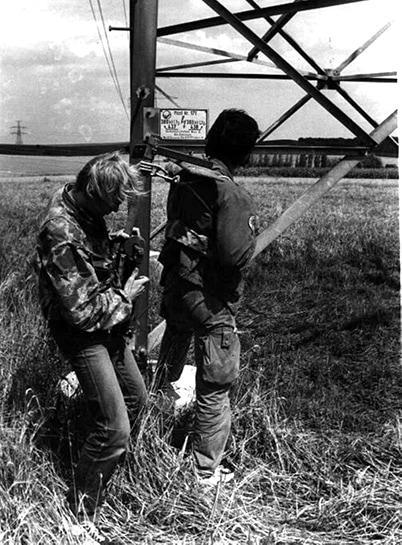

The students broke through the surface inside a former outhouse-turned-storage shed right under the noses of German Democratic Republic (GDR) border guards with orders to shoot to kill if they saw anyone try to flee to the West.

It was the perfect cover to carry out what would be the most successful mass escape from East Berlin, an endeavor known simply as "Tunnel 57" in recognition of the number of people who crawled out on October 3-4, 1964.

When the time came, potential escapees were given precise times to approach Strelitzer Strasse 55 on the East German side. There they uttered the code word "Tokyo" to get past the West German student manning the entrance. A second student guided them to the tunnel entrance, and a third through the tunnel -- well below the wall, the "death strip" of spikes, and all the other barriers designed to keep GDR citizens behind the Iron Curtain.

Twenty-eight people made it out the first night. By midnight of October 4 another 29 were freed before a potential escapee betrayed the cause, and border troops arrived to shut down the operation with guns blazing.

The students all had their reasons to breach the Berlin Wall, erected in surprise move on August 13, 1961, imprisoning friends and family members in East Germany.

Kabisch wanted to free his cousin, who had asked that spring: "Can you do anything for me? I must get out of here," he told the Thai newspaper The Nation.

Neumann wanted to free his girlfriend, Christa Gruhle, who was about to finish a 16-month sentence for a failed escape attempt.

"Some did it even if they had nobody they wanted to get out," Kabisch told The Nation. "They were so angry at the system."

The GDR had taken great pains to prevent defections, closing the border with the West in 1952, and making unauthorized departures punishable by three years' imprisonment in 1957. But more than 3 million GDR citizens had left by 1961, approximately one-sixth of the Soviet satellite's population, prompting the decision to erect the Berlin Wall and significantly fortify the length of the border with West Germany.

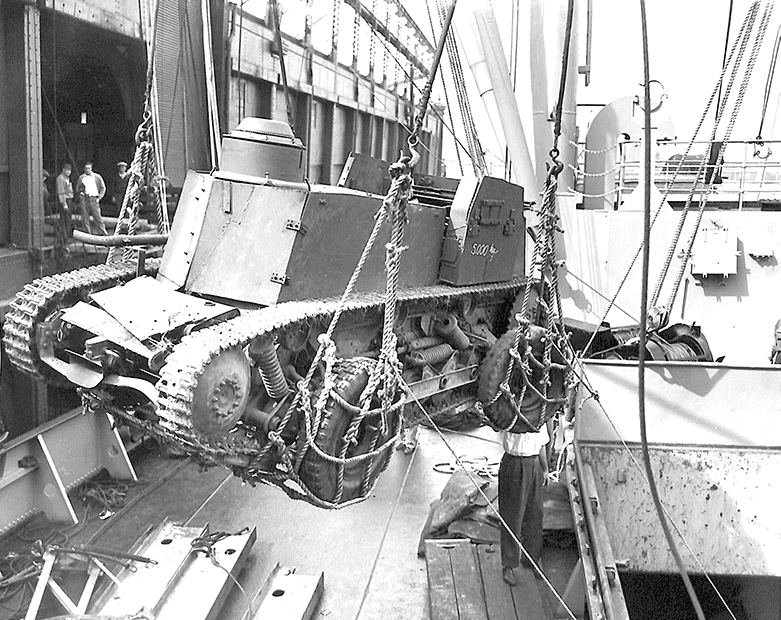

The wall, 12 meters high and ringed with barbed wire and protected by tank traps, ran the length of the 155-kilometer border around the exclave of West Berlin. It was just part of an extensive system that was deadly effective in keeping East Germans behind the Iron Curtain. According to the Berlin-based Foundation for the Study of Communist Dictatorship in East Germany, at least 138 people were killed trying to cross the Berlin Wall from 1961 until passage was permitted in 1989; 75,000 escape attempts failed.

Around 40,000 did succeed in escaping from East Germany over that time, however, including more than 300 by way of one of the 70-odd tunnels dug by student activists like Kabisch and Neumann.

While a great success, the Tunnel 57 escape did not end peacefully. Shots were exchanged in the dark as the West German students scurried to avoid capture by the GDR border guards.

One guard, Egon Schultz, was shot and killed, and the East German authorities were quick to blame young, West German radicals.

Upon hearing on East German radio that they were being accused of killing Schultz, the students protested by sending message-carrying balloons over the Berlin Wall.

"The murderer is the East German secret police," the message read. “The real murderer is the system that addressed the massive flight of its citizens not by removing the cause of the problem, but by building a WALL and giving the order for Germans to shoot Germans."

Three decades later, after the fall of the wall and the reunification of Germany, the true cause of Schultz's death was revealed -- he had been killed by a fellow border guard.

"They used this as propaganda," Kabisch said of the East Germans in his 2014 video interview. "The boy that had been hit was hit by his own."