The timing and location of Martin Manhoff's work suggest spy. The artistic images he left behind suggest something else.

By Mike Eckel, Wojtek Grojec, and Amos Chapple

Cold War Development

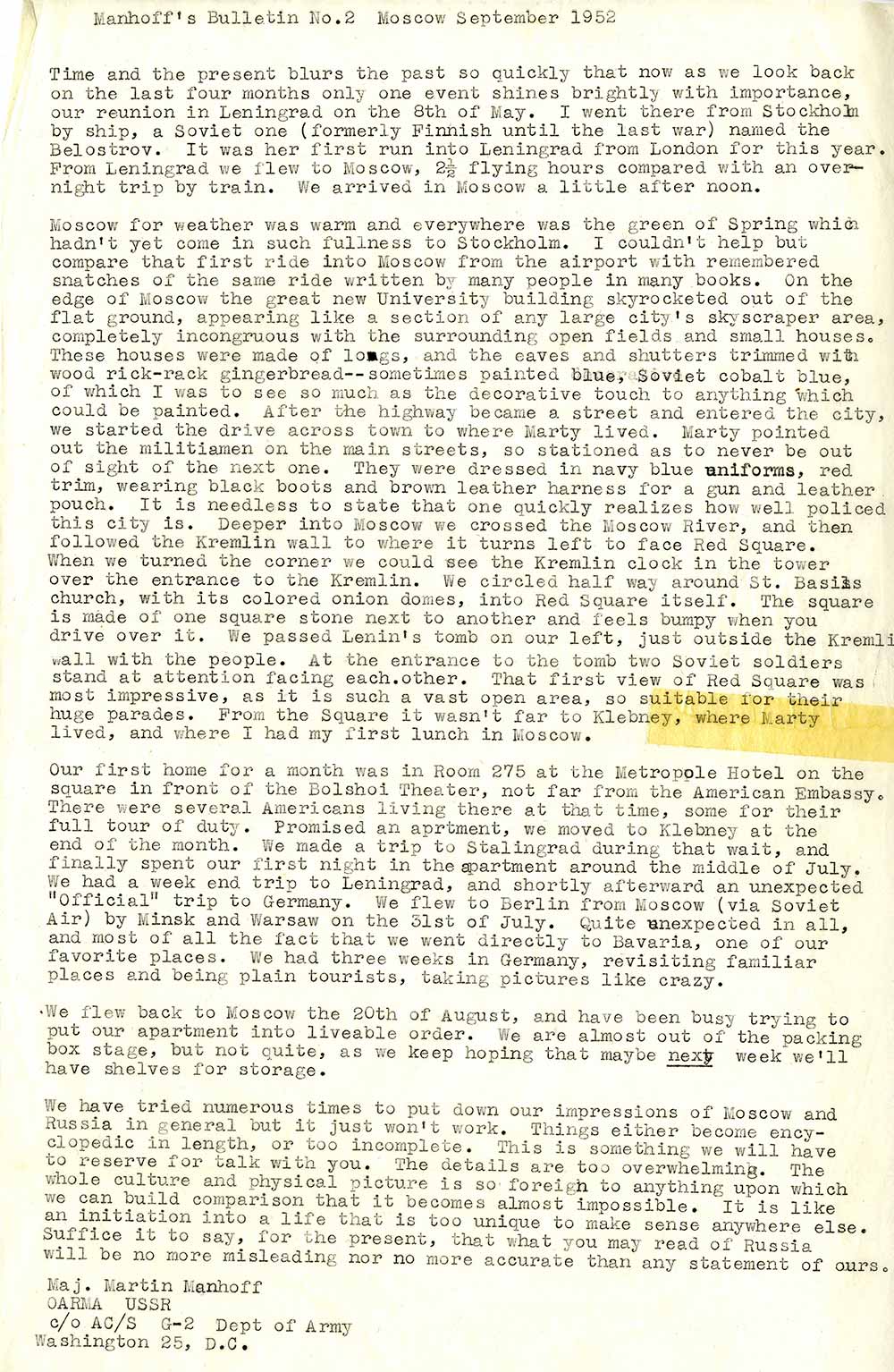

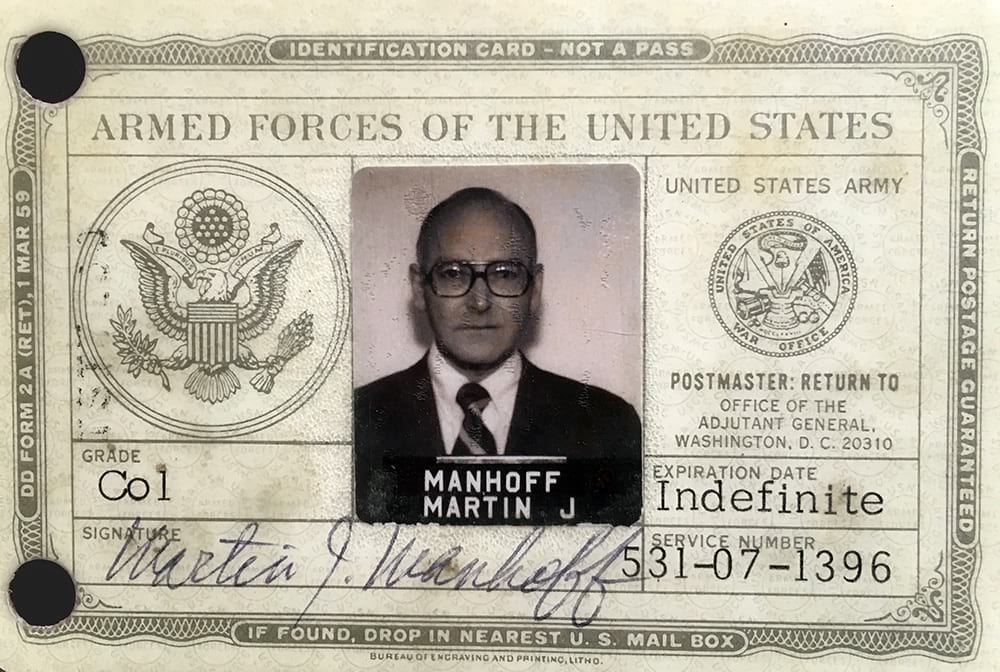

Martin Manhoff left the Soviet Union on June 1, 1954, a little more than two months after a powerful newspaper accused him and three other U.S. military attachés of spying during a cross-country train trip.

There is no direct evidence that Manhoff was a spy during his time in the U.S.S.R. His military records contain no indication that espionage was a formal part of his duties. After the Soviet newspaper Trud alleged that the Americans had been taking note of various infrastructure while traveling the Trans-Siberian Railway, U.S. authorities declined to comment. And to this day U.S. intelligence agencies refuse to discuss the issue. When queried, a CIA spokeswoman told RFE/RL that the agency does "not verify personnel status, even of people who have since passed away."

That Major Manhoff, a decorated veteran of World War II, might have been more than an avid amateur photographer is not out of the question, however.

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

When he entered his service in Moscow in February 1952, the U.S. Embassy overlooked the Kremlin's northwestern walls — an ideal location to document the comings and goings of Politburo members and other top political officials.

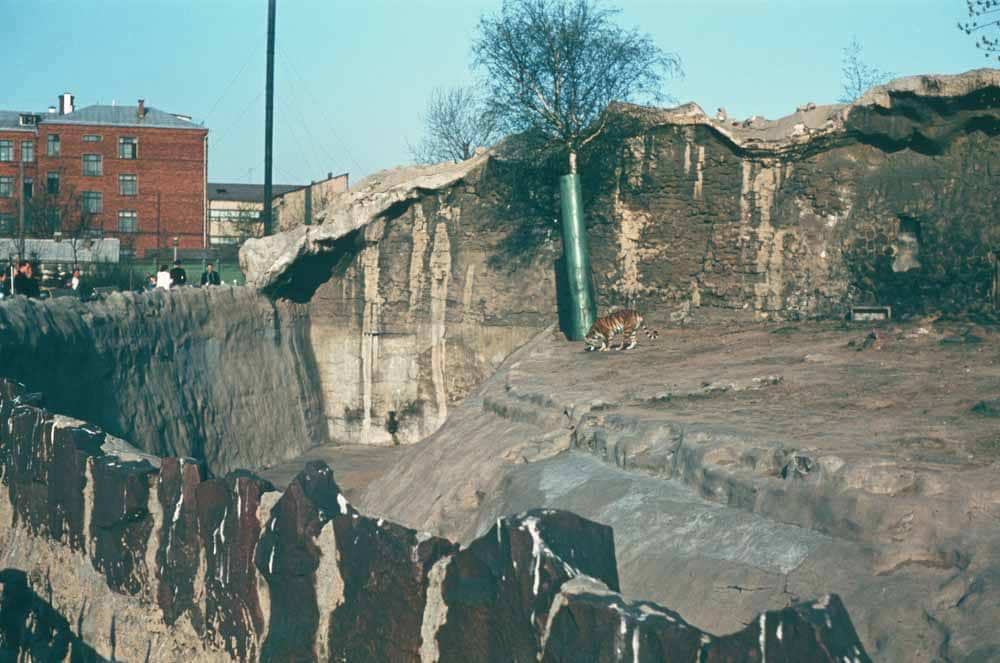

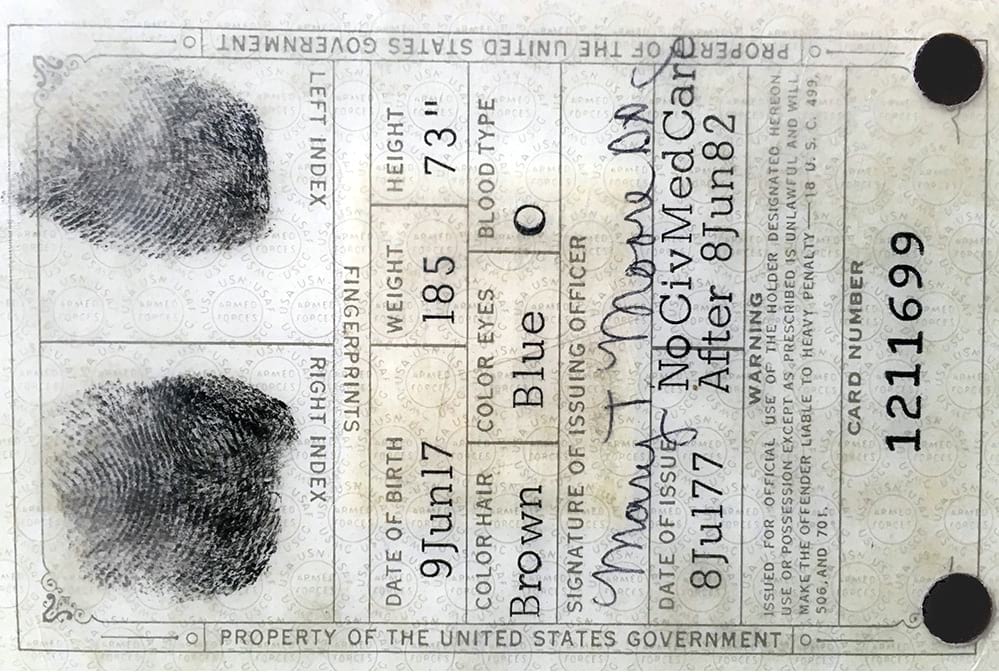

The quality of the images Manhoff took during his 27 months in the Soviet capital suggests he had access to film and developing equipment that was all but unavailable to the public. The stamps on some of the film canisters found on the Manhoffs' property — "Confidential," "Top Secret," and "Property of USAAF" — indicate that his work may have had some classified component to it.

Manhoff's personal records indicate that he had been trained for some classified activities. The year before departing for Moscow, he received "Clearance for Cryptological Information," and he later took a three-month training course at the military's Strategic Intelligence School. That training appears to have been aimed at instructing Manhoff to send and receive encrypted cables and other communication at the Moscow embassy.

One document found in Manhoff's files suggests that, three years after returning to the United States from Moscow, he sought to work with the Central Intelligence Agency.

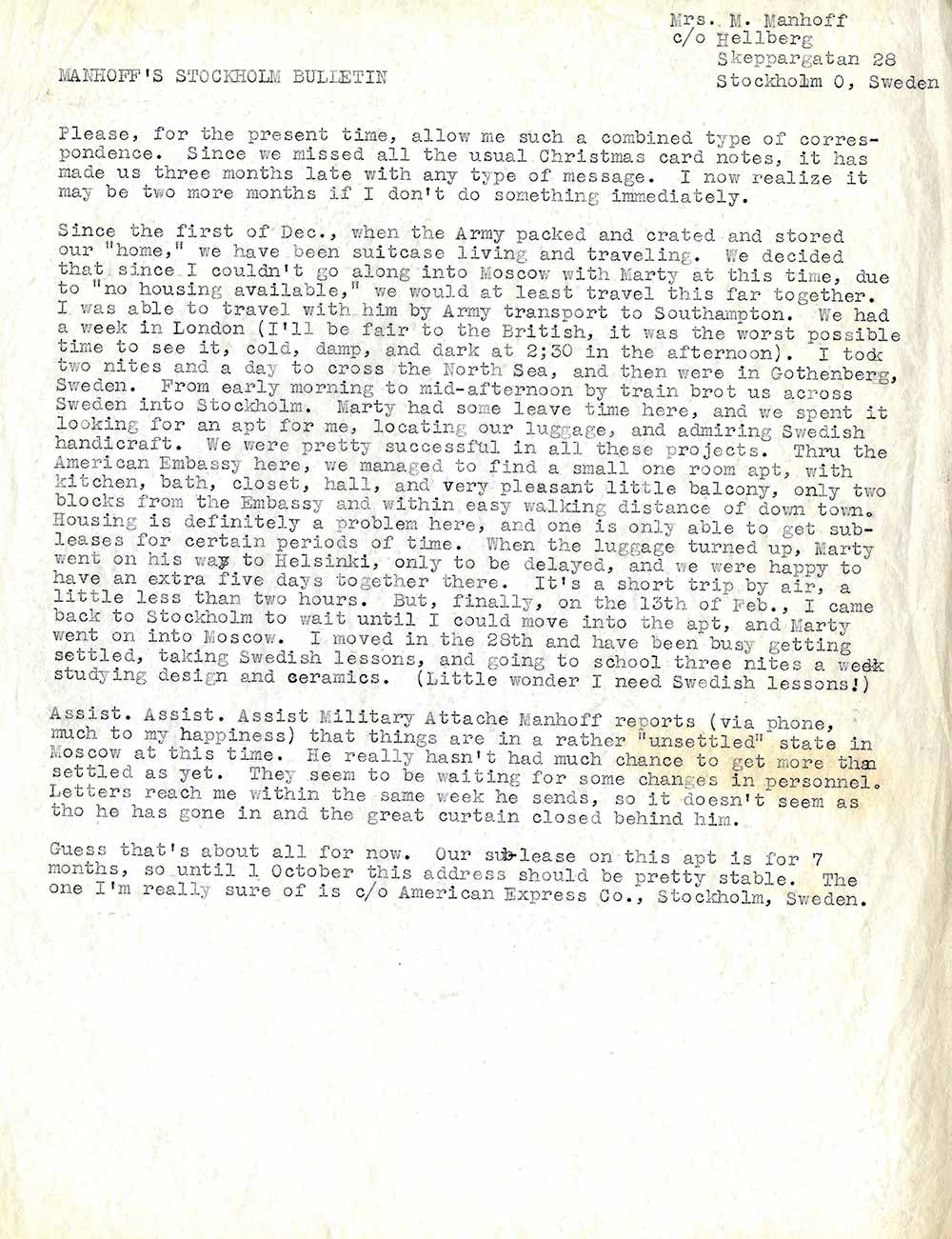

But there are ample signs that Manhoff and his wife Jan, who were just three years into their marriage when they moved to Moscow, were also just curious, adventurous travelers.

Prior to the war, Martin received a bachelor's degree in fine arts at the University of Washington; afterward, he took classes at New York University's Institute of Fine Art. Jan, too, was an art student, having returned to school following a one-year stint with the Red Cross.

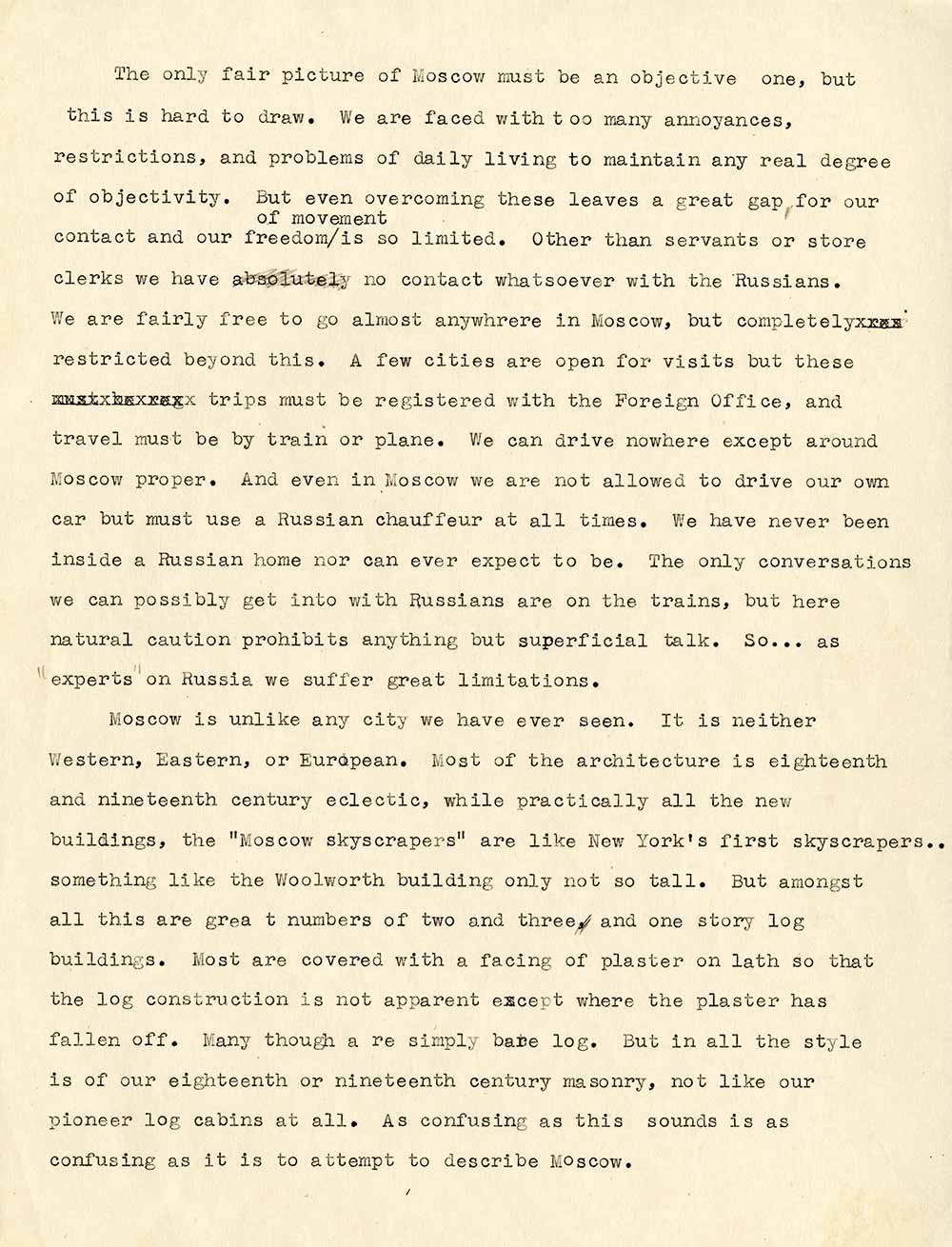

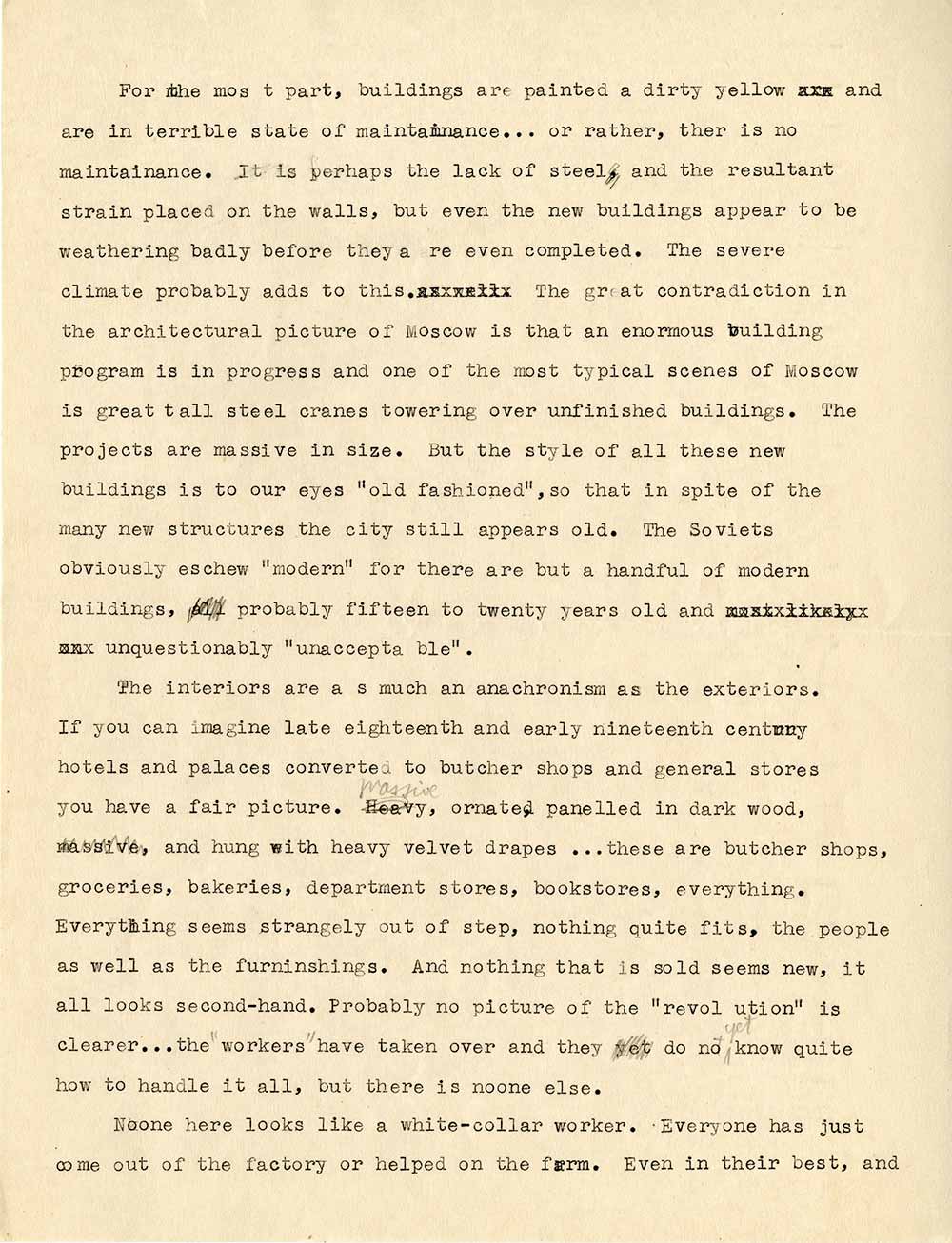

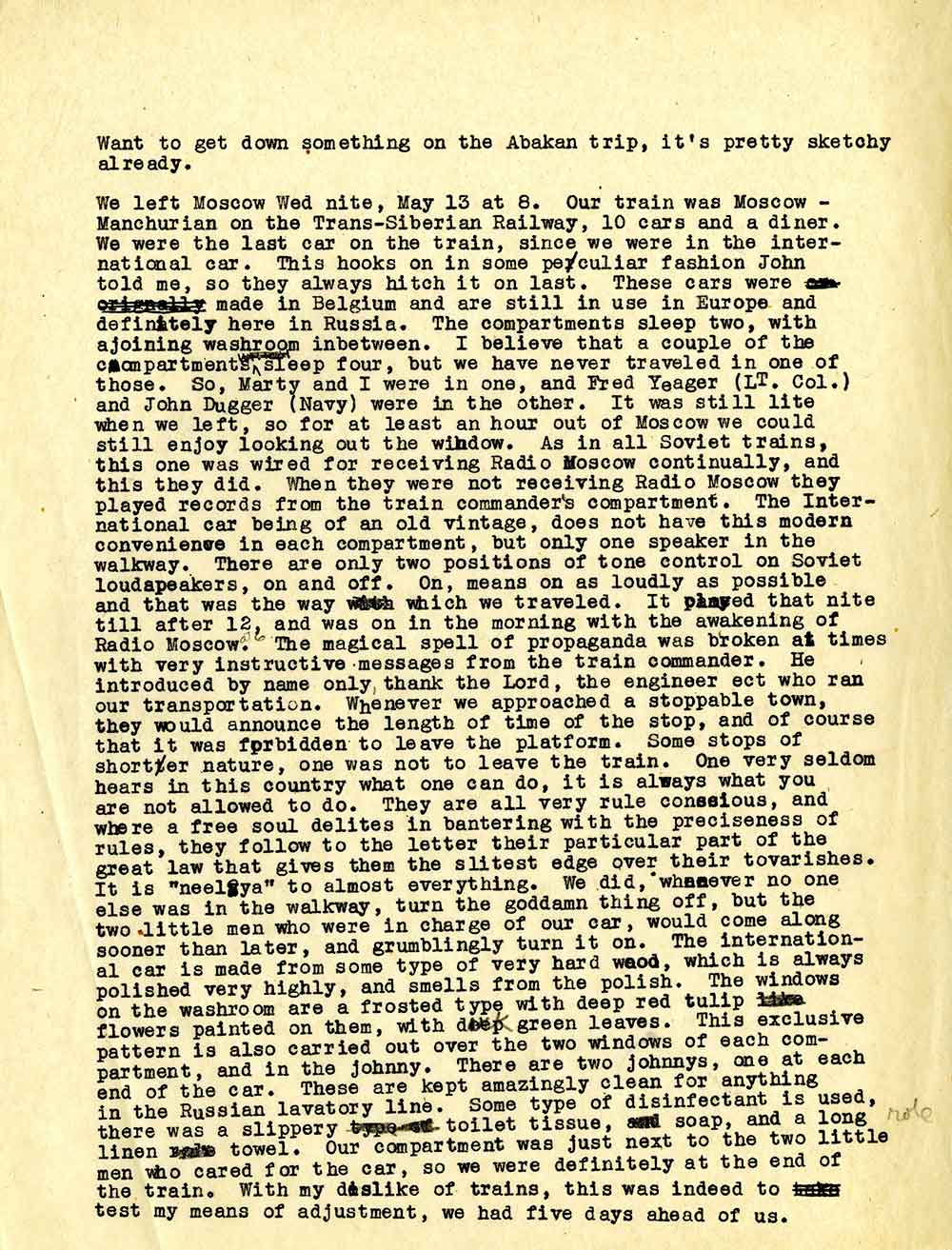

Jan's letters to friends and relatives reveal a keen interest in everyday life in the Soviet Union, and the realization that their time there would be treated with such suspicion came as an obvious disappointment.

"Other than servants or store clerks we have no contact whatsoever with the Russians," she writes in one undated letter. "The only conversations we can possibly get into with Russians are on the trains, but here natural caution prohibits anything but superficial talk."

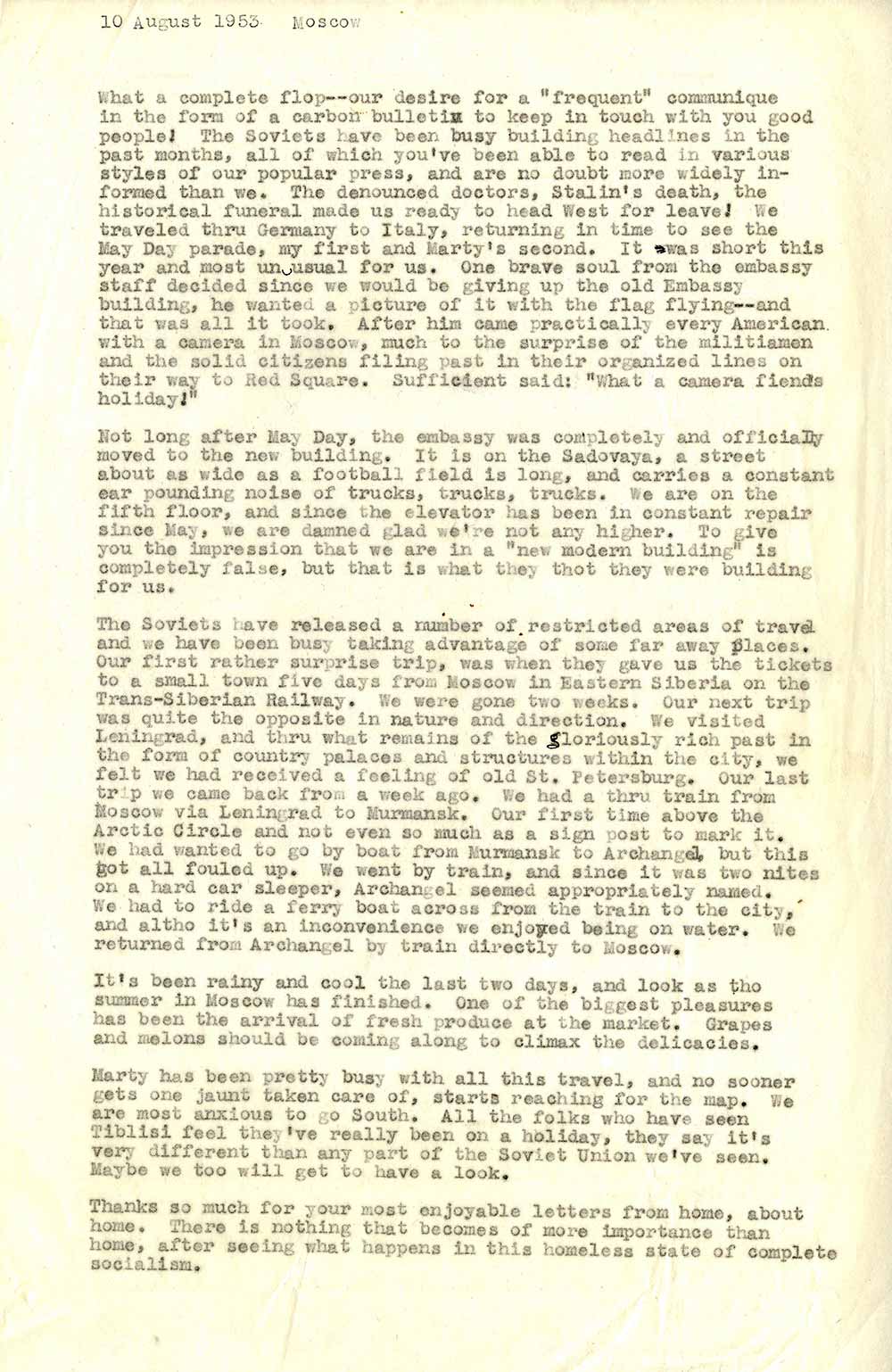

In the thaw that followed the March 1953 death of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, restrictions on foreigners were loosened, including travel and local prohibitions against taking photographs. As the Seattle Times wrote in the wake of the spying allegations against him: "Almost weekly now, Americans and other Westerners are making trips into the interior along approved routes."

This new development offered the Manhoffs respite from Moscow life — even an opportunity for Jan to visit her mother's birthplace, Ukraine.

The Soviets have been busy building headlines in the past months, all of which you've been able to read in various styles of our popular press, and are no doubt more widely informed than we. The denounced doctors, Stalin's death, the historical funeral made us ready to head West for leave!

Jan Manhoff, letter home, dated August 10, 1953

See all the letters. Tap/click a letter to view it full-screen.

"Marty has been pretty busy with all this travel," Jan writes in late 1953. "And no sooner gets one jaunt taken care of, starts reaching for the map."

Douglas Smith, the Seattle historian who helped discover the wealth of documents and letters, 16 mm film reels, and color photographs the Manhoffs left behind, said the artistic quality of Martin's images reflect the eye not of a spy, but of an aspiring photographer.

"He seems like he was someone more interested in documenting life inside Russia, not with any specific military, diplomatic intelligence gathering," Smith says. "Plus, if he was engaged in espionage, why did he have this stuff at his home?"

About a month after the couple's departure from Moscow — and four months after Trud publicly accused Martin and other American officers of spying — the first hints of what had happened behind the diplomatic scenes emerged. On July 6, 1954, The New York Times reported that three Soviet diplomats had been accused of espionage and expelled from the United States: two in February, and one in June.

The expulsions were not public knowledge, though they were almost certainly known to Manhoff and U.S. Embassy officials at the time. Another short article in the Times cited a diplomatic note from the Soviet Foreign Ministry accusing two of Manhoff's fellow military attachés and traveling partners of being spies, and ordering them expelled.

There was no mention of Manhoff.

The Times also reported that the U.S. Embassy in Moscow denied that the two officers, or any other members of the embassy, had "engaged in activities incompatible with their diplomatic status." The U.S. State Department told the paper that "it is obvious that the Soviet authorities have taken this action in retaliation for the expulsion in recent months of three Soviet officials for espionage and improper activities in this country."

Five months after leaving Moscow, Martin was honorably discharged from the Army. He and Jan returned to the Seattle, Washington, area where they were both from. Later, they opened a store in nearby Kirkland, selling modern home furnishings from around the world, according to an article in a local newspaper from 1956.

The couple had no children, and lived out their lives in a low-slung, nondescript house in Kirkland, hidden from a busy road by high shrubbery.

In addition to running the store, Martin worked part-time at his father's framing shop in Seattle. Later in life, as the Manhoffs' business struggled to stay open, he took a job as a tax assessor. Jan pursued her artwork — in watercolors, textiles, and other media.

Martin died in September 2005. Jan died nine years later, and it fell to an old friend to oversee their will. The friend, who asked not to be identified to avoid unwanted publicity, described the Manhoffs as pack rats — the house was cluttered with trinkets and antiques from their travels, but also things like magazines going back decades. The friend sold at auction what she could to pay for the trust established by the will.

Next door to the house, in the former auto-body shop that had been owned by Jan's father, the friend found cardboard boxes stacked to the ceiling. She found Martin's army foot locker, and his old uniform. She found war records, personal files, and souvenirs jammed into different kinds of boxes, like those used to hold vegetables.

Mixed into the jumble were metal slide boxes, along with Kodak and Agfa film boxes. And she found gray, disc-shaped canisters used to store reels of film.

Overwhelmed by the task of clearing out the main house, the friend contacted Smith in July 2016 to help figure out what to do with what would ultimately become the Manhoff Archives.

Smith said he was stunned, particularly by the color images taken at a time when color photography was virtually unknown to the general public, never mind in the post-war Soviet Union.

Some of the slides were identified with penciled remarks written on scraps of paper, such as "Crimea Trip Show." Some of the slide boxes had notes scribbled on them, or scratched-off notes from other events.

"It was a mish-mash of boxes, notes scribbled on them here and there," Smith recalls. "It gave you the impression that when he had had all these materials developed for the first time, he wrote it down in pencil, quickly, once more, then packed it up and then appeared to forget about it."

"It literally sat for 60 years."