From a balcony with a view to the Kremlin, Major Manhoff shot the only known independent footage of Stalin’s funeral.

By Mike Eckel, Wojtek Grojec, and Amos Chapple

Turning Point

U.S. Army Major Martin Manhoff had been in Moscow for more than a year when on March 5, 1953, after several days of ominous reports in the Communist Party mouthpiece Pravda, Josef Stalin died. His death was announced publicly the following day by Pravda and other state media.

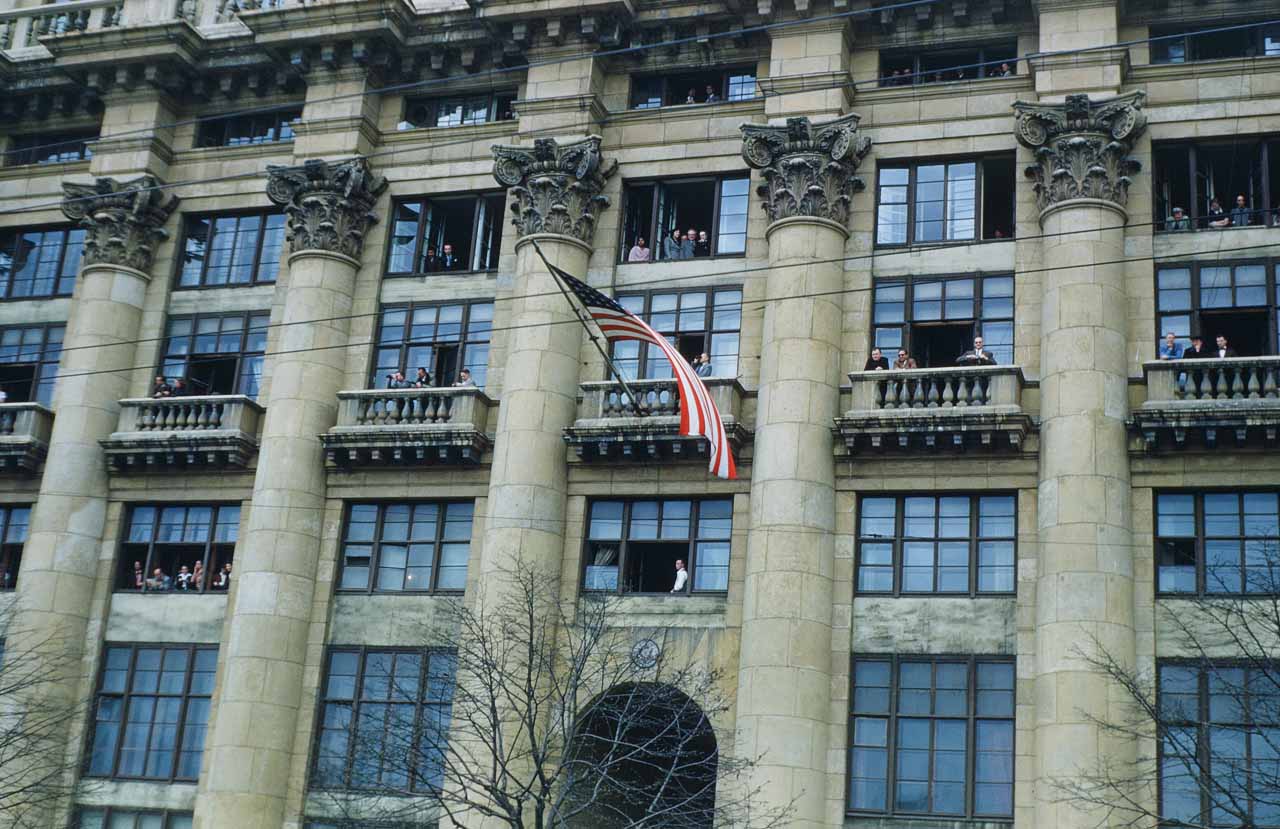

There is no written record in Manhoff's files of his reaction to the Soviet dictator's death. What the assistant army attaché did leave to history, however, was the only known independent footage of Stalin's funeral procession.

Manhoff's films, shot in full color, show hundreds of soldiers dressed in long trench coats forming a lengthy cordon for Stalin's body to be brought to Red Square. A procession of dozens of dignitaries — members of the Politburo and other high officials — is seen carrying massive funeral wreaths.

One close-up shows the casket – draped in red and decorated with Stalin's trademark military cap, and featuring what appears to be a window for viewing his face. The casket is carried on a caisson, pulled by a team of horses and escorted by soldiers carrying bayonet-fitted rifles. They are followed by hundreds of people. Other historical images shot by official Soviet photographers show the pantheon of Communist leaders who either served as pallbearers or escorts: Nikita Khrushchev, Lavrenty Beria, Vyacheslav Molotov, and others.

The film then peers from a distance into Red Square, where crowds of officials mass in front of Lenin's Mausoleum to hear eulogies by the Politburo’s leadership. Stalin’s embalmed body is later interred in the mausoleum next to the body of the Soviet leader he succeeded, Vladimir Lenin.

Manhoff's films appear to be one of a kind. Most, if not all, news reels of Stalin's funeral — including those used in Western news programs like the BBC — used Soviet state footage, the best example being the 1953 official documentary called Velikoye Proshchaniye, or The Great Farewell, produced by the Central Studio for Documentary Films.

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

To be sure, Manhoff was filming while officially working as a U.S. government employee, and there is good reason to believe that the footage was viewed by U.S. intelligence agencies looking for hints of who might succeed Stalin.

What makes it stand out is its raw, unedited quality, an unfiltered look at a tectonic moment in Soviet history.

One scene Manhoff shot from his vantage point at the then-U.S. Embassy shows crowds streaming across nearby Manezhnaya ploshchad, as hundreds of people rush to the bottom of Kremlyovsky proyezd, the short incline leading up to Red Square.

Other footage shows soldiers standing guard on Kremlyovsky proyezd jumping up and down and clasping their arms in an attempt to stay warm on a cold March day, something that’s unseen in any official films.

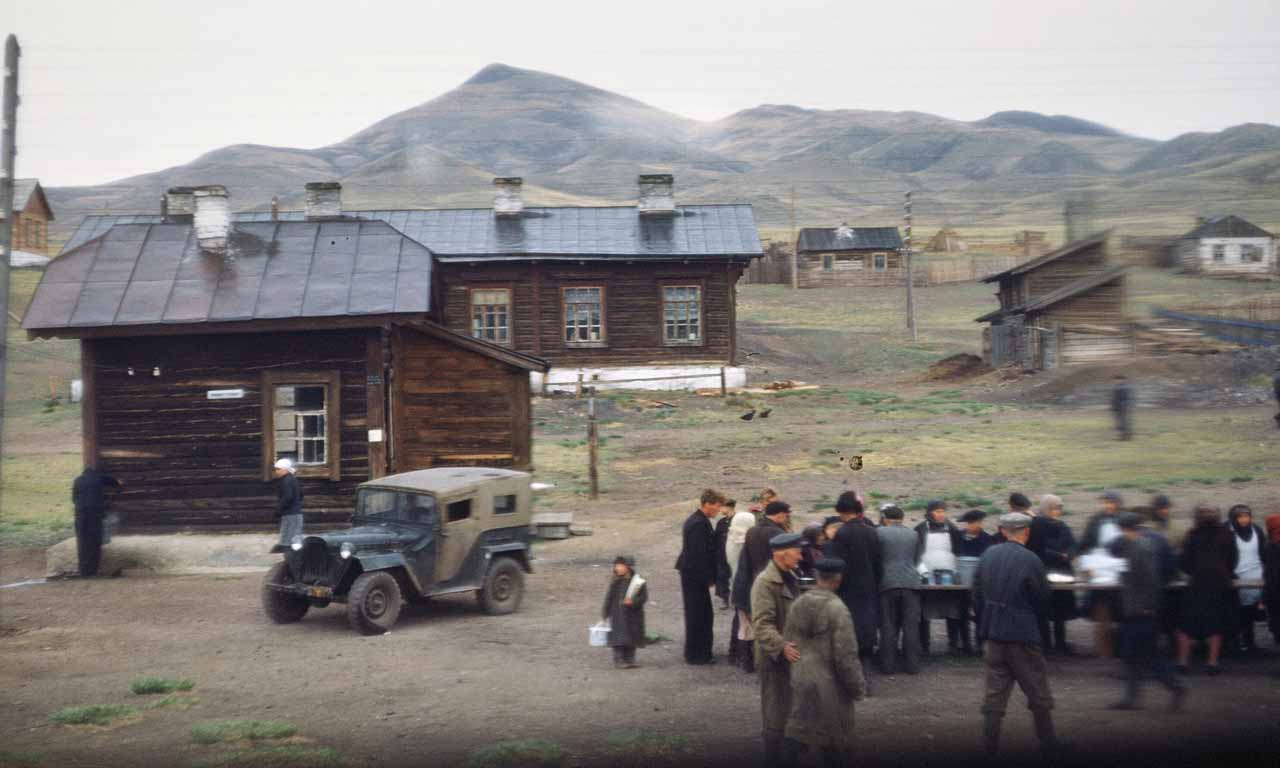

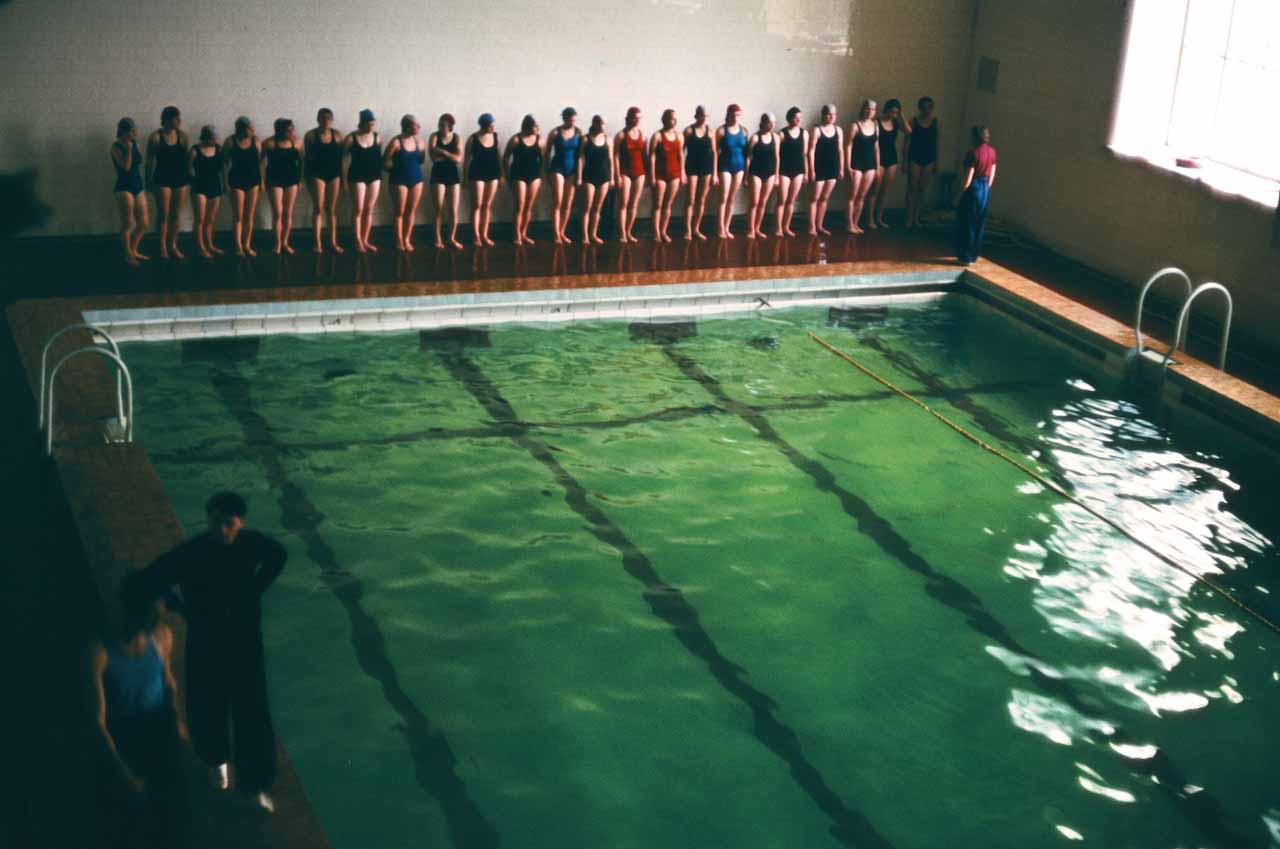

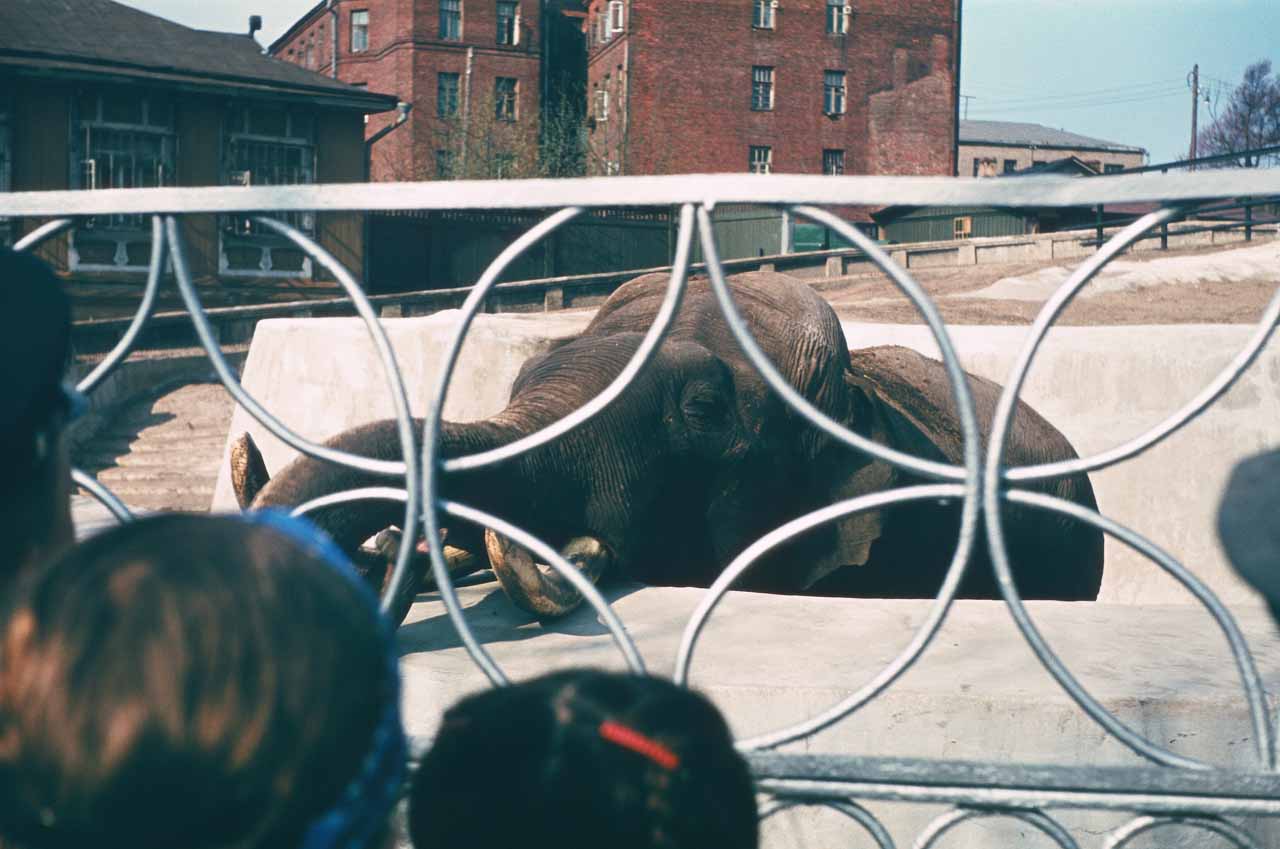

Such unfiltered views of Soviet life highlight the uniqueness of the Manhoff Archive, according to Douglas Smith, the Seattle-based historian who discovered the collection and provided exclusive access to RFE/RL.

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

Manhoff "captured this everyday quality, both in his photographs and his movies," Smith says. "It gives it a human quality that is missing from any other depiction."