The Manhoffs left behind a colorful portrait of Soviet city life through their photos and letters.

By Mike Eckel, Wojtek Grojec, and Amos Chapple

Breaking The Ice

Whether shooting Moscow street scenes from a chauffeured car, or writing home about their experiences, U.S. Army Major Martin Manhoff and his wife Jan were piecing together an intimate, vivid portrait of life behind the Iron Curtain in the early 1950s.

Martin's official duties as assistant army attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow were to serve as a liaison to Soviet military contacts. In all likelihood, however, he was also there to gather intelligence and peer into the vast changes going on in the U.S.S.R. as it emerged from the devastation of World War II and the Cold War deepened.

The large collection of color photographs and 16 mm film he shot reveals the rapid development of Soviet infrastructure. Martin's images clearly show the construction of the Stalinist skyscrapers known as the "Seven Sisters," and other projects intended to symbolize the U.S.S.R.'s emergence as a superpower.

But they also stand on their own artistically, evidence of an eye drawn to streetscapes, skylines, and people's everyday lives, not to mention the pageantry intrinsic to communist rule.

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

One of his numerous color films, taken from the balcony of the U.S. Embassy overlooking the Kremlin, records the choreography of Young Pioneers — the white-shirted, red-kerchiefed youth group set up as a communist answer to the Boy Scouts — marching in tight formation through Manezhnaya ploshchad on May Day.

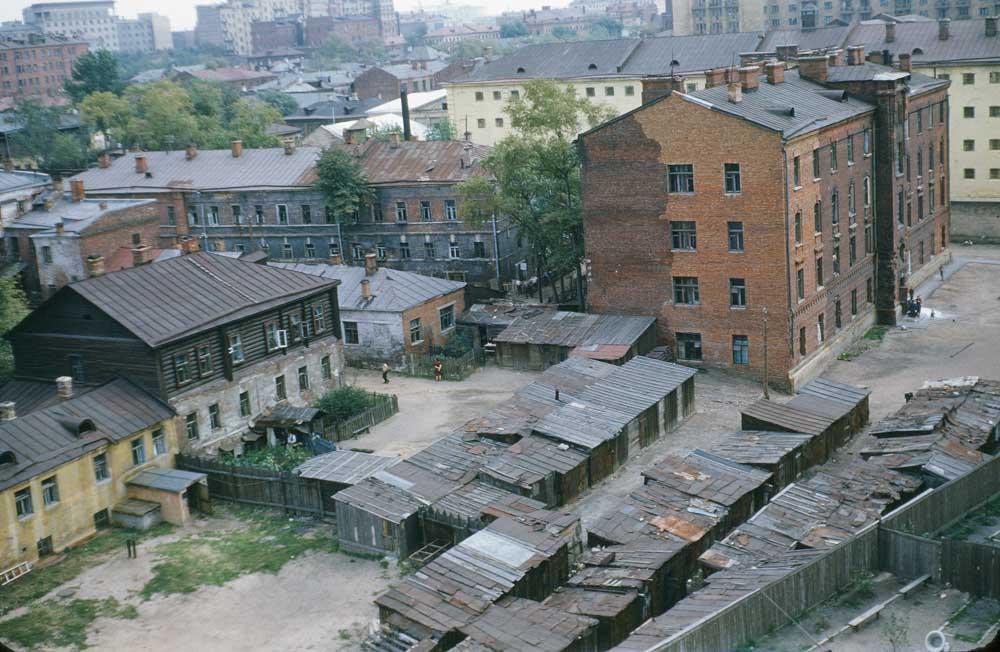

A relay race on a summer day, steam billowing over a snow-capped Kremlin, families enjoying a day in courtyard squalor, the hustle and bustle of a rapidly growing capital — these are among the films' most moving images.

The recently discovered Manhoff Archives contain no written record of Martin's personal thoughts of his time in the Soviet Union. But Jan gives a wealth of observations in letters she wrote to friends back home following her arrival in Moscow in May 1952, three months after her husband.

Typed on long-since yellowed stationery, and carefully corrected in her own hand, the letters reveal Jan's first impressions of life under Stalin's thumb. "It is needless to state that one quickly realizes how well policed this city is," she writes of her arrival.

"When we turned the corner we could see the Kremlin clock in the tower over the entrance to the Kremlin. We circled half way around St. Basils [sic] church, with its colored onion domes, into Red Square itself," she adds. "That first view of Red Square was most impressive, as it is such a vast open area, so suitable for their huge parades."

Later in the same letter, dated September 1952, she makes obvious efforts not to be too judgmental about the new environment she finds herself in. "The whole culture and physical picture is so foreign to anything upon which we can build comparison that it becomes almost impossible," she writes. "It is like an initiation into a life that is too unique to make sense anywhere else."

I couldn't help but compare that first ride into Moscow from the airport with remembered snatches of the same ride written by many people in many books. On the edge of Moscow the great new University building skyrocketed out of the flat ground, appearing like a section of any large city's skyscraper area, completely incongruous with the surrounding open fields and small houses. Those houses were made of logs, and the eaves and shutters trimmed with wood rick-rack gingerbread -- sometimes painted blue, Soviet cobalt blue, of which I was to see so much as the decorative touch to anything which could be painted.

Jan Manhoff, September 1952

As the Manhoffs settled in, Jan's comments show greater familiarity with Soviet life and, at times, clear frustration – particularly with the restrictions that were placed by Soviet authorities on foreign diplomats. "We can drive nowhere except around Moscow proper," she complains. "And even in Moscow we are not allowed to drive our own car but must use a Russian chauffeur at all times. We have never been inside a Russian home nor can ever expect to be."

Tap/click any image to view the gallery full-screen.

She strains to stay positive. "The only fair picture of Moscow must be an objective one, but this is hard to draw," she writes. "We are faced with too many annoyances, restrictions, and problems of daily living to maintain any real degree of objectivity."

Moscow is unlike any city we have ever seen. It is neither Western, Eastern, or European. Most of the architecture is eighteenth and nineteenth century eclectic, while practically all the new buildings, the 'Moscow skyscrapers' are like New York's... But amongst all this are great numbers of two and three, and one story log buildings. Most are covered with a facing of plaster on lath so that the log construction is not apparent except where the plaster has fallen off. As confusing as this sounds is as confusing as it is to attempt to describe Moscow.

Jan Manhoff, undated letter

In another letter, undated but appearing to come later in their stay in Moscow, Jan appears outright jaded. "One very seldom hears in this country what one can do," she states. "It is always what you are not allowed to do."

In describing average citizens of the Soviet Union and the conditions they lived in, she at times takes a patronizing tone and is dismissive of the communist ideal of the Soviet Union being a workers' paradise. "Noone [sic] here looks like a white-collar worker. Everyone has just come out of the country or helped at the farm," she writes. "Even in their best, and clean as they may or may not be, clothes don't fit, colors don't match."

If you can imagine late eighteenth and early nineteenth century hotels and palaces converted to butcher shops and general stores you have a fair picture..... Everything seems strangely out of step, nothing quite fits.... And nothing that is sold seems new, it all looks second-hand. Probably no picture of the "revolution" is clearer ... the "workers" have taken over and they do not yet know quite how to handle it all, but there is noone else.

Jan Manhoff, undated letter

Most of the Manhoffs' time in the Soviet Union was spent in Moscow. But Martin and Jan also traveled to other parts of the country. On at least three occasions in 1952 and 1953 they visited Leningrad, the northern second city that today bears its original name, St. Petersburg. "We visited Leningrad, and thru what remains of the gloriously rich past in the form of country palaces and structures within the city, we felt we had received a feeling of old St. Petersburg."

They traveled farther afield: to Murmansk, the Arctic Sea port that was home to the Soviet Northern Fleet; to Kyiv, the capital of what was then known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic; to Yalta, the famed Crimean resort that hosted the 1945 conference where Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin decided Europe's postwar fate.

And they made at least two trips aboard the Trans-Siberian Railroad: to the central Siberian region of Khakassia, and to the distant city of Khabarovsk, on the Chinese border.

It was on the journey to Khabarovsk, in March 1954, that the final chapter of the Manhoffs' Soviet adventure began.