As attacks on vessels in the Red Sea have shown, conflict can disrupt global trade. Countries and shipping companies need reliable alternatives to keep the world economy humming.

This lesson was learned in the heart of Eurasia in February 2022 when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threw global supply chains into upheaval and opened up new geopolitical battlegrounds.

Enter the Middle Corridor, aka the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route.

The thousands of kilometers of roads, railroads, and ports that connect China to Europe had long been championed, but it was the prospect of a long war in Ukraine that shifted the calculus in Beijing and European capitals.

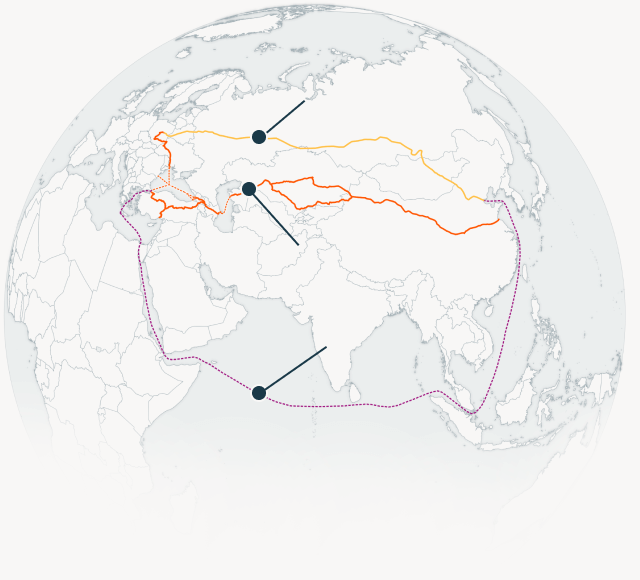

Northern Corridor

Middle Corridor

Ocean Route

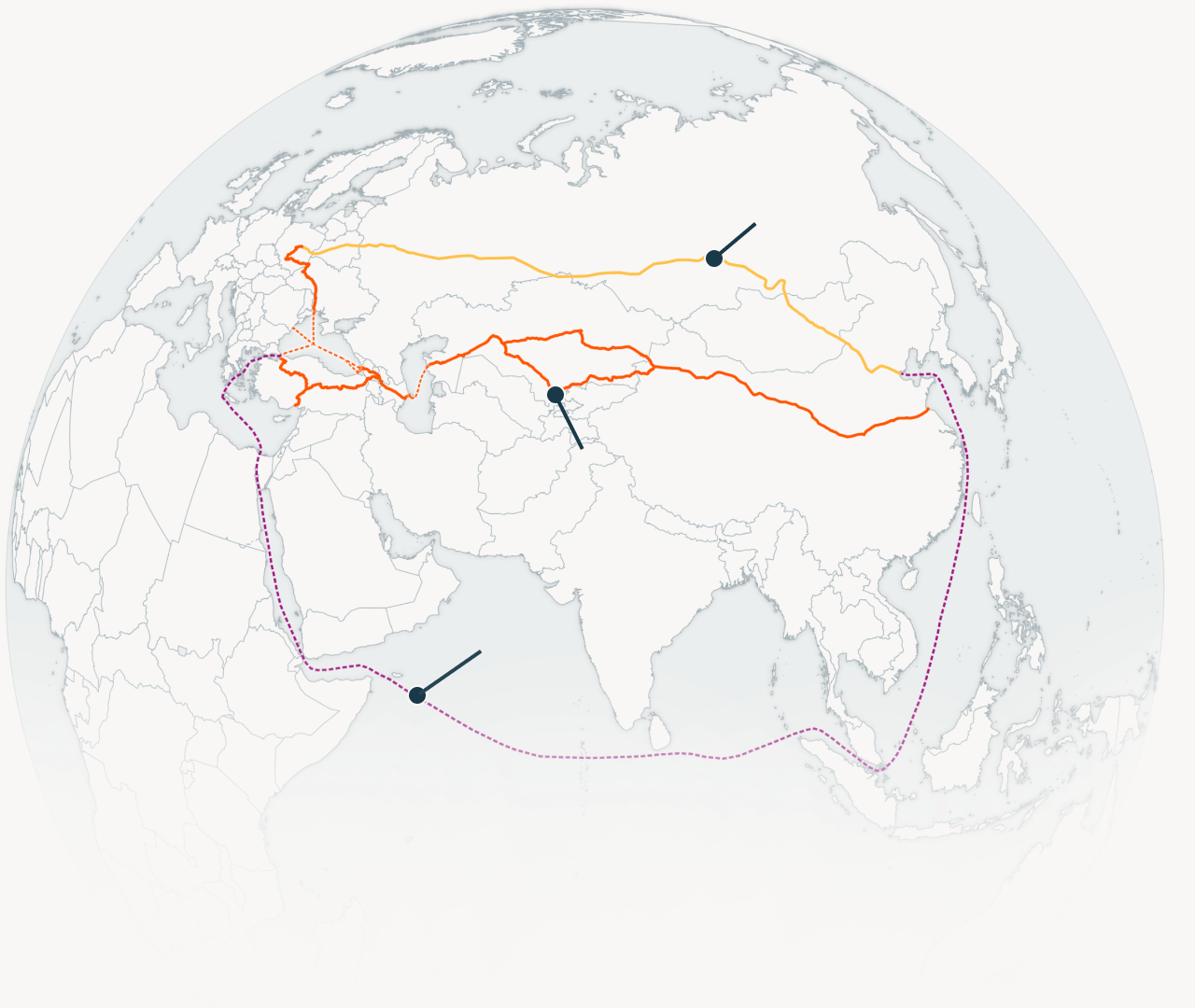

Ocean Route

Middle Corridor

Northern Corridor

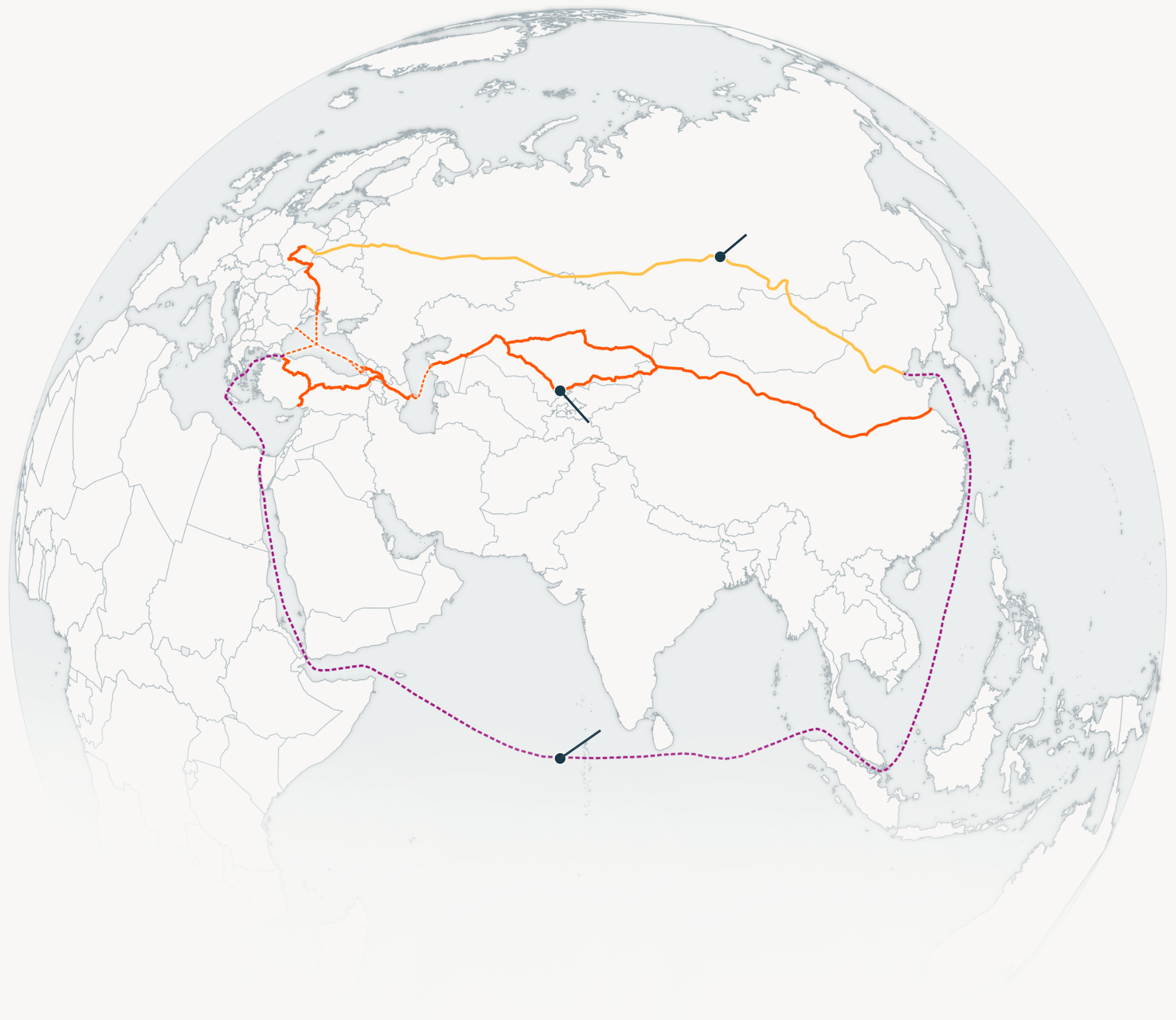

Ocean Route

Middle Corridor

Northern Corridor

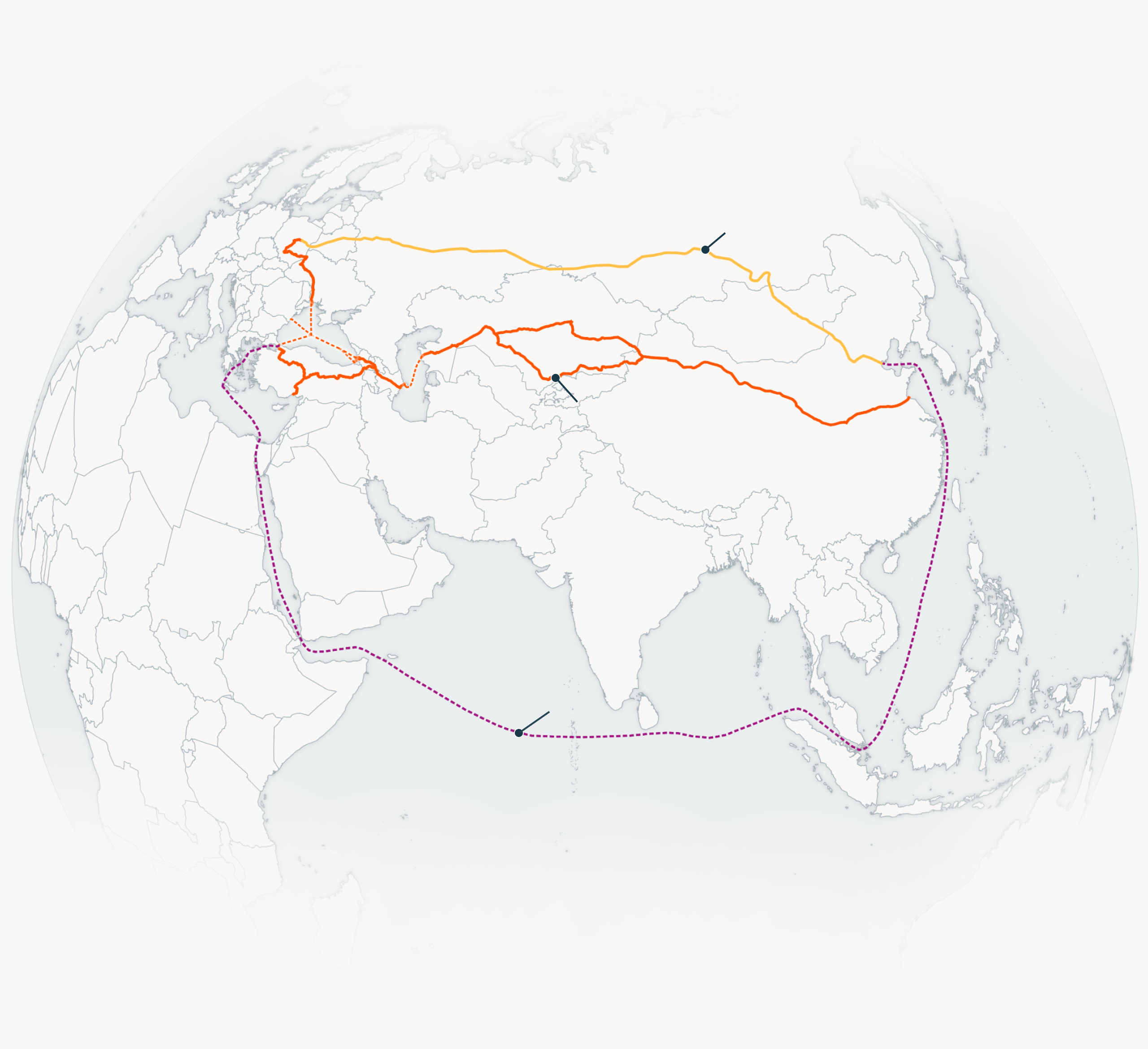

Ocean Route

Northern Corridor

Middle Corridor

Before the war, the majority of overland trade between China and the European Union traveled along Russia’s vast rail network to connect two of the world’s largest markets. This better-developed northern route gave cargo companies a predictable, affordable trade network.

As a result, Russian trains became the main mode of transport for China-EU overland trade.

But Russia’s invasion changed that, as cargo companies had to navigate sanctions and find new trade routes linking Europe and China that bypassed Russia.

“Transit between Europe and Asia is becoming more complicated and more expensive by the day,” Romana Vlahutin, a German Marshall Fund fellow and former EU ambassador-at-large for connectivity, told RFE/RL.

Thus the Ukraine war breathed new life into the Middle Corridor after it had been avoided for years due to rising costs, border issues, and a lack of quality infrastructure.

“The Middle Corridor would be the shortest multimodal corridor, and there is a genuine interest from the Central Asian states to have more robust and much closer links with the EU,” said Vlahutin.

Enticed by the mega-route’s potential, cargo traveling along the Middle Corridor skyrocketed from 350,000 tons in 2020 to 3.2 million tons in 2022. According to a World Bank study released in late 2023, trade volume on the Middle Corridor could triple by 2030, reaching 11 million tons.

But the Middle Corridor’s limitations -- ranging from a lack of infrastructure to soaring wait times in ports and at border crossings -- still need to be overcome.

“Much will depend on how China perceives the Middle Corridor,” Emil Avdaliani, international relations professor at the European University in Tbilisi, told RFE/RL. “Without Chinese cargo, there will be little incentive to expand the route.”

The EU has also moved to further develop infrastructure in Central Asia and the Caucasus; other countries have sensed opportunity, with billions of euros in new investments. Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Kazakhstan agreed to set up a body that would accelerate development, and they are working to improve coordination and lower trade barriers.

Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, China’s western autonomous region, has slowly grown into a key hub for China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since the massive infrastructure project was launched in 2013.

NaN/21With strong internal connections to domestic Chinese centers like Xi’an, some 2,500 kilometers east of Urumqi, the city has become a launching pad for the rail networks in Kazakhstan that form the early strands of the Middle Corridor.

NaN/21Moving West To Kazakhstan

Cargo from China to Kazakhstan goes through two main crossings. The first is Dostyk, which was the main port of entry for goods traveling north to Russia but also connects to railways moving west; and the second is Khorgos, which was built as one of China’s key BRI investments in Central Asia.

NaN/21Khorgos, Kazakhstan

Roughly 2,500 kilometers from the nearest coastline, Khorgos was launched in 2015 and dubbed a “dry port" as a terminal designed to process overland cargo.

Upon arrival, goods heading west are transferred by cranes from Chinese trains to Kazakh ones that have the same track gauge as Russia and most other former Soviet countries. The next such transfer isn’t required on the journey to Europe until entering the EU.

NaN/21Aqtau, Kazakhstan

After entering through Khorgos, goods turn south towards Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, and then west by rail to the Caspian port city of Aqtau.

NaN/21Crossing the Caspian

Aqtau, a city of roughly 180,000 people, sits on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea and is the Middle Corridor’s principal maritime port on the Central Asian side, where it transports cargo to Azerbaijan.

The Kazakh government is investing tens of millions of dollars into the port and announced plans to expand it in late 2022. The U.A.E. and Kazakhstan also agreed in September 2022 to inject $900 million into projects that support the Middle Corridor.

NaN/21

The journey across the Caspian Sea is where the Middle Corridor’s first obstacles appear.

The sea is known for its rough waters during the summer that can delay ferries for weeks, which only worsens the already bad congestion in Azerbaijan due to a lack of infrastructure and logistics centers to unload and transfer cargo.

As the World Bank said in a 2023 Middle Corridor study, the longest delays along the route occur at sea crossings due to “a shortage of vessels, followed by errors in shipping documentation.” The report added that high costs, unpredictability, and a lack of cargo tracking systems are all major problems for the Caspian crossing.

Forecasts show that if the Middle Corridor is to reach its upper projections and take advantage of its shorter route between Europe and Asia, then solving these logistical issues is a necessity.

The biggest gains could be for regional trade between Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan, which could increase by 37 percent by 2030, and by 28 percent between those countries and the EU alone, according to World Bank projections.

NaN/21While a lack of ports presents a bottleneck for the Middle Corridor, container capacity is also limited due to the size of the ports on the Caspian. This is especially true for Baku, whose port has more limited capacity than Aqtau.

Azerbaijani authorities announced expansion plans and were investing in new infrastructure for the port outside of Baku before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Once completed, this could also align with other infrastructure projects in Central Asia, such as a prospective China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway line and expanded capacity in Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan’s main Caspian port.

NaN/21As the World Bank and other organizations have noted, one of the largest inefficiencies along the corridor exists at Baku’s port, where the dwell time for goods is high.

One study said the average wait time for containers in Baku’s port yards was 25 days, with a range of 10-46 days for shipments. This period was calculated to account on average for 70 percent of the total shipping time for a one-way journey across the entire Middle Corridor.

NaN/21Armenia is not officially part of the Middle Corridor's route, but there are talks to possibly include it. The route currently travels through Azerbaijan and Georgia to the Black Sea, but a proposed 43-kilometer rail route through Armenia's Syunik Province to the Azerbaijani exclave of Naxcivan and then to Turkey would connect the Caspian and Mediterranean seas. Realizing the proposed "Zangezur Corridor" would first require a normalization of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, who are bitter rivals.

NaN/21Once processed in Azerbaijan, containers go west by rail and road to Georgia, traversing the capital, Tbilisi.

The Georgian government has been building and modernizing its transit infrastructure to more easily bring goods across its mountainous terrain to its Black Sea ports at Poti and Batumi or southwest to continue the journey by land to Turkey.

NaN/21Several new multilane highways have been built across the country, with the most high-profile being a 51.6-kilometer section that cuts through the rugged terrain of the Rikoti Pass. The project was awarded to Chinese construction companies and is estimated to cost close to $1 billion.

The highway -- which consists of 96 bridges and 53 tunnels -- is currently behind schedule but will cut transit time from Tbilisi to the Black Sea in half once completed.

NaN/21Overland To Turkey

Kars, located in northwest Turkey near its borders with Armenia and Georgia, is the main point of entry by land into the country via the Middle Corridor.

Shipments can enter by road and rail, but the World Bank says reconstruction of the lines connecting from Georgia are needed if it is to accept larger quantities of goods.

NaN/21

Well before its route was settled, Turkey had pushed its own vision for the Middle Corridor as a way to build stronger economic ties to Central Asia and improve its strategic position among its neighbors.

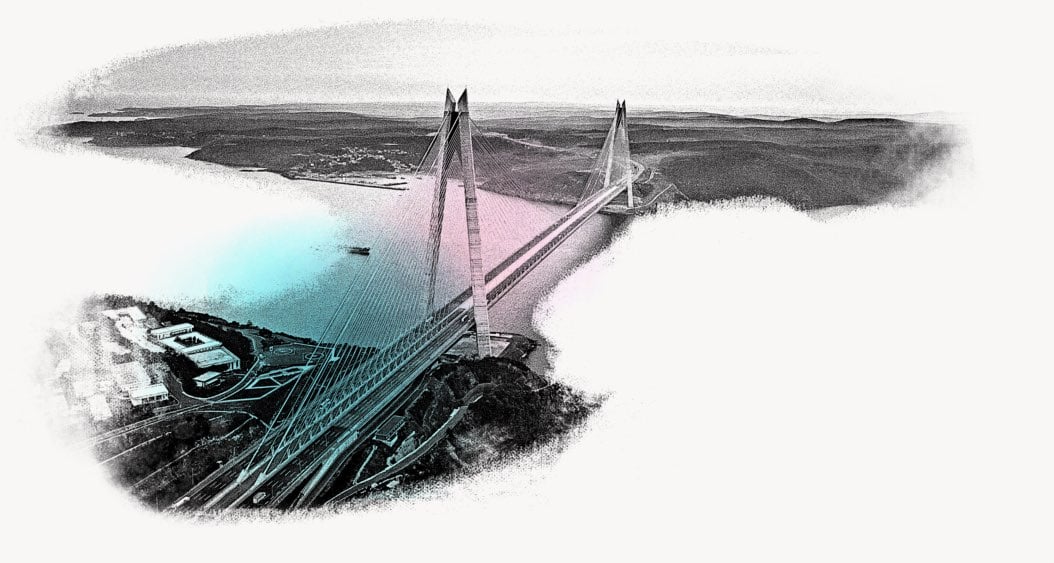

Between 2013 and 2015, Ankara signed agreements with Azerbaijan, China, Georgia, and Kazakhstan to boost the Middle Corridor and completed new projects to improve connectivity, including the Eurasia Tunnel and Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge in Istanbul in 2016. Turkey is also in the process of finishing a new high-speed railway connection to Kars and a northern highway to more easily bring goods to Istanbul.

Despite this level of interest, Turkey’s overall position within the Middle Corridor is uncertain, with the World Bank’s 2023 comprehensive study saying the country’s position and alternative routes will be studied in more detail in a future report.

NaN/21Back To Georgia

Georgia’s ports of Poti and Batumi account for 76 percent and 24 percent of all Georgian container flows, respectively, and the country’s location on the eastern edge of the Black Sea has made it particularly crucial for the Middle Corridor to take off.

But Georgia’s potential has thus far been limited by long lines of trucks at its borders and ports at Batumi and Poti operating near capacity.

Currently, the country has no deep-sea port, which would allow larger ships to transport increased volumes at a more efficient rate, something that organizations like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank say is necessary to make the Middle Corridor globally competitive.

NaN/21This has revived plans in Georgia to build a deep-sea port in Anaklia, a town farther north on the country’s coastline. In May, the Georgian government announced it had awarded a 49 percent ownership stake to a Chinese consortium, as well as contracts to build and operate a new port there.

A previous attempt to build the port in Anaklia by a consortium led by Georgia's TBC Bank and U.S.-based Conti International broke ground and moved residents from the future site of the port in 2018. That bid was eventually canceled by the government in 2020 after years of political jostling, and the area has sat empty ever since.

NaN/21Poti is also looking to expand and increase its capacity for larger ships, although its narrow entrance could still limit the number of ships it can handle compared to Anaklia.

Most projections, however, show that Georgia is unlikely to need both an expanded Poti port and a new deep-sea one in Anaklia. This leaves room for Georgia’s port politics to still play out in unpredictable ways.

NaN/21Crossing the Black Sea

From Georgia, goods can transit across the Black Sea or cut south towards Turkey but, due to major infrastructure gaps along the land route, the maritime route, which serves three destinations -- Istanbul, Constanta, and Chornomorsk -- is preferred by operators.

Similar to the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea presents new obstacles in terms of high tariffs, slow processing, and inefficient customs procedures. Added to this is the instability and uncertainty brought by the war in Ukraine that have seen attacks and tensions across Ukrainian and Russian portions of the Black Sea.

NaN/21The Black Sea port at Constanta is where the Middle Corridor enters the EU after traveling roughly 5,000 kilometers.

Because of its port on the Black Sea, Romania has been one of the most engaged EU members on developing the Middle Corridor, with Romanian officials stepping up their engagement with Georgia and looking to integrate the route into the platform of official bodies governing the Black Sea.

NaN/21Ukraine’s Chornomorsk port has rail and sailing connections to Varna in Bulgaria, Batumi and Poti in Georgia, and Samsun in Turkey, making it a strategic location along the Middle Corridor.

However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has cast a shadow over how integral it will be as the route progresses.

Chornomorsk’s location and Ukraine’s comparatively developed rail network make it an attractive option, but with fighting under way in Ukraine, the port’s place in the Middle Corridor will ultimately be determined by how the war ends.

NaN/21Poland was the main destination for the northern route that traveled through Russia and Belarus to the EU, where goods would then make their way across Europe.

That infrastructure is now being put to use as the Middle Corridor gathers steam. Warsaw has strong road and rail connections to Romania and Ukraine and is a gateway to other markets within the bloc, such as neighboring Germany and the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

From here, goods also pass on their journey back east to the Caucasus, Central Asia, and China, where they once again encounter the same obstacles that governments across the trade route are trying to solve.

NaN/21New Momentum And Old Problems

There’s no denying that the Middle Corridor has attracted a new level of energy and interest from major companies and countries that wasn’t present before but, despite this momentum, it’s still struggling with inefficiencies that keep costs high and trade unpredictable.

Economists are undecided on the route’s future, but its role as a land bridge between China and Europe that bypasses Russia will continue to draw interest as countries and companies look for alternative trade routes amid a volatile geopolitical climate.

Projections show that the route could one day reduce transit time between China and Europe to 12 days, compared to 19 days along the northern route through Russia and 22-37 days for maritime trade that runs to and from China via the Indian Ocean.

Whether the governments along the Middle Corridor can realize this vast potential will be decided in the coming years.