click

Srebrenica was a beleaguered small town in eastern Bosnia-Herzegovina in July 1995 brimming with some 42,000 people -- more than 80 percent of them refugees -- at the tail end of a vicious war.

It had no idea its name – after a series of massacres killed more than 8,000 male Bosniaks -- would forever be synonymous with genocide.

Bosnian Muslims had flocked to Srebrenica from 13 different nearby towns because it was a United Nations-designated "safe area." Unfortunately no security was found as the menfolk were brutally slaughtered and more than 25,000 women, children, and elderly deported from the zone.

The Srebrenica events were planned by the Bosnian Serb military and this timeline will use the archives of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to show documents, testimonials, and official verdicts showing how the first genocide in Europe since World War II was organized and carried out.

In the first ICTY verdict, against Bosnian Serb army Deputy Commander Radislav Krstic in 2001, the court established that genocide had occurred in Srebrenica.

According to the Institute for Missing Persons of Bosnia-Herzegovina and numerous international verdicts, more than 8,000 people were killed in the Srebrenica massacre. The remains of some 6,955 people have been identified and reburied.

Although a lot of verdicts have been issued, many of the perpetrators of the genocide have not been brought to justice.

Strategic Srebrenica

During the more than three-year war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the area around Srebrenica -- in the Podrinje region where Bosnia borders Serbia on the Drina River -- was of great strategic importance to Bosnian Serbs.

Gaining control of this Bosniak enclave would mean the Serb forces would have full authority over all of eastern Bosnia along the Serbian border.

At the start of the war, on May 12, 1992, Momcilo Krajisnik, the self-declared president of the assembly of the "Republika Srpska," signed a Decision On The Strategic Goals Of The Serb People In Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In it, Strategic Goal No. 3 required "the establishment of a corridor in the Drina River Valley or the elimination of the Drina [River] as a border between Serbian states."

Directive No. 4

General Ratko Mladic, the commander of Bosnian Serb forces, issued Directive No. 4 in mid-November.

In the document, he orders the Drina Corps, one of five corps in the Bosnian Serb army, to "inflict as many losses as possible on the [enemy] and force it to leave the areas of Birac, Zepa, and Gorazde that have Muslim populations."

Having destroyed dozens of predominantly Bosniak villages amid heavy fighting between Bosnian Serb and Bosniak armies, tens of thousands of inhabitants of Bosniak villages in the Drina River Valley found refuge in the enclaves of Srebrenica, Zepa, and Gorazde. Directive No. 4.

First Evacuation

From March to April 1993, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) evacuated between 8,000 and 9,000 Bosniaks from Srebrenica.

On April 13, 1993, Bosnian Serb forces informed UNHCR representatives that they would attack the city if "Muslims did not surrender and agree to be evacuated from the enclave."

Resolution 819

Faced with a humanitarian catastrophe due largely to a stranglehold by Bosnian Serb forces, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 819, which demanded that all parties to the conflict in Bosnia-Herzegovina consider Srebrenica and the surrounding area a “safe area” in which there would be no armed attacks or other hostilities.

The Security Council's Resolution 824, declaring a "safe area," was adopted on May 6, 1993. There were then about 40,000 people in Srebrenica.

Demilitarization Deal

Bosnian Serb and Bosnian generals Ratko Mladic and Sefer Halilovic, respectively, negotiated an agreement on the demilitarization of Srebrenica on April 17.

The deal meant there would be a cease-fire in the Srebrenica area, the deployment of UN "blue helmet" troops (the UN Protection Force, or UNPROFOR), unhindered passage from Tuzla to Srebrenica for both sides, and the surrender of weapons.

"No armed person or unit will remain in the city except UNPROFOR, which will remain in the city when the demilitarization process is complete," it said.

'Blue Helmets' Arrive

The first group of UNPROFOR forces arrived in Srebrenica on April 18. A new group of soldiers would arrive on a rotating basis approximately every six months. The peacekeepers had light weapons and at no time numbered more than 600 troops.

A small command center was set up in Srebrenica and a larger main base in Potocari, about 5 kilometers north. There were also 13 observation posts along the enclave's border.

'An Open Prison'

At the end of April, a UN Security Council report stated that there were 70,000 people in the enclave. Many of them were refugees from neighboring villages that had been destroyed by Serb forces.

The report said people were being deprived of drinking water, there was no electricity or basic medical supplies, and it declared the situation "dramatic."

"Fortunately, humanitarian convoys with food are arriving, but they are the subject of constant harassment at checkpoints and at the entrance to the city, which is contrary to Resolution 819. Helicopters transporting the wounded have been subjected to similar treatment."

The report added that the "Serbs are determined to show that they [are keeping] the city under control, that it is at their mercy, that they did not take Srebrenica just because of the adoption of Resolution 819."

"Srebrenica today is the equivalent of an open prison, where people can walk around but they are controlled and terrorized by the increased presence of Serb tanks."

Directive No. 7

A Dutch battallion came in January 1995 and it reported that the situation was worsening, as supplies were not being allowed into the enclave. Some 200 of the "blue helmets" who had gone on leave were not permitted by Bosnian Serb forces to return to the base, leaving just 400 members of the batallion there.

But the Bosnian Serbs had, according to the verdict against former Drina Corps Deputy Commander Radislav Krstic, between 1,000 and 2,000 soldiers from the three brigades of the Drina Corps stationed around the enclave.

A Bosnian Army unit that had remained in the enclave, the 28th Division, was reportedly neither well organized nor equipped.

Two months later, the Bosnian Serb strategy to remove Bosnian Muslims from Srebrenica was formulated in Directive No. 7.

On March 8, 1995, the self-declared president of the "Republika Srpska," Radovan Karadzic, signed the directive, which ordered the army to "create conditions of total insecurity, intolerance, and hopelessness for the further survival and lives of the locals in Srebrenica and Zepa."

It added: "In the event that UNPROFOR forces leave Zepa and Srebrenica, the [Drina Corps] command will plan an operation called 'Jadar' with the task of breaking up and destroying Muslim forces in these enclaves and definitively liberating Podrinje."

'Inflict As Many Losses'

Bosnian Serb army Deputy Commander Radislav Krstic, who had recently been promoted to the rank of major general, issues an emergency order on June 4 with the task of "inflicting as many losses as possible on the enemy and capturing enemy soldiers."

Eliminating Enclaves

Bosnian Serb army Commander Ratko Mladic issued an order for Operation Krivaja '95, the code name for an attack on Srebrenica to reduce the size of the enclave, on July 2.

"The goal of the action: to completely separate and narrow the enclaves of Srebrenica and Zepa with a sudden attack, to improve the tactical position of the forces in the depth of the zone, and to create conditions for the elimination of the enclaves."

As there was no real resistance from either the Bosnian Army troops or the Dutch battalion in the enclave, as well as no NATO air support, Mladic's forces moved close to Srebrenica on July 10 with nothing preventing them from entering the "safe area."

Safe-Zone Attack

After the issuance of Directive No. 7 and Operation Krivaja '95, the attack on the UN "safe area" of Srebrenica began in the early morning of July 6. The area was guarded by some 450 UNPROFOR "blue helmets" and a poorly armed Bosnian Army

People Starving

Srebrenica municipality head Osman Suljic wrote to the Bosnian government in Sarajevo that the 32,000 displaced people in Srebrenica were joined in the last three days -- after Bosnian Serb attacks -- by some 4,000 more people. "We have no food supplies at all, the population is mostly starving," Suljic wrote.

He added that he was again and perhaps "for the last time" appealing for help from the people in Podrinje.

"As I write this, four Chetnik (Serb) tanks are operating in the city, we don’t know anything about the number of dead, but the number is large, [and] it is impossible to transport the wounded to the hospital. UNPROFOR cannot help itself or the people; they suggested at this morning's meeting that [any extra UNPROFOR soldiers should react] and prevent genocide."

Take Srebrenica

Drina Corps Major General Radislav Krstic issued an order stating: "using the achieved success with the necessary regrouping of forces, continue the attack on Srebrenica energetically and decisively."

Late on July 9, the Drina Corps moved 4 kilometers into the enclave, just 1 kilometer from Srebrenica. Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic issued an order giving the Drina Corps the green light to take Srebrenica.

'All Should Be Killed'

In testimony at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the case against former Serbian/Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, Miroslav Deronjic, a member of the war commission in Bratunac, near Srebrenica, described a conversation he had with Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic on July 9, 1995.

"Karadzic asked me: 'What do you, Miroslav, intend to do with that population down there?'... I answered him something like this: 'Mr. President, I cannot even imagine the development of events when entering Srebrenica.' I told him that it was futile to assume, since many indicators are unknown to me, [and] we did not know whether the [Bosnian] army would surrender, how the population would behave.… Karadzic said the following: 'Miroslav, all [these people] should be killed.' And then he added, 'You manage everything.'"

Deronjic was later sentenced to 10 years in prison for participating as a co-perpetrator in criminal activity in the village of Glogova near Bratunac. Witness statement

Shelling Begins

Bosnian Serbian forces began by shelling Srebrenica. Part of the population ran toward Potocari, about 5 kilometers northwest, hoping they would be safe at the UN compound there.

Late on July 11 about 25,000 refugees -- mostly women, children, and the elderly -- gathered in Potocari. Witnesses later estimated there were at least 300 men as well at the UN base and between 600 and 900 outside the base.

Mladic Enters

The population fled to Potocari seeking security from the "blue helmet" troops. Late on July 11, more than 30,000 refugees had gathered there, mostly women, children, and the elderly.

Bosnian Serb army Commander Ratko Mladic, accompanied by General Milenko Zivanovic (commander of the Drina Corps) and Major General Radislav Krstic (deputy commander of the Drina Corps), entered Srebrenica on the afternoon of July 11.

"Here we are on July 11, 1995, in Serbian Srebrenica. On the eve of another great Serbian holiday we are giving this city to the Serbian people. And finally the moment has come for us to take revenge on the Turks in this area,” Mladic said.

Column Formed

The Bosnian Army's 28th Division and Srebrenica municipal officials decided to form a column made up mostly of men to cut through a forest to territory under Bosniak control, near Tuzla.

The column of some 15,000 moved from the villages of Jaglici and Susnjari north toward Konjevic Polje and Bratunac at about midnight. A day later, Bosnian Serb forces launched an attack on a convoy from the column crossing the road between Konjevic Polje and Nova Kasaba, breaking it into two parts. Only about one-third of the men survive the journey.

One of the survivors testified at The Hague about these events.

Witness P: "We simply could not and did not believe [it was safe] for the male population to go to Potocari. [We couldn't trust them]...and it was normal [to think] that [we] would be killed...so only women and children could go to Potocari."

Judge: "When you say 'we couldn't trust them,' who do you mean?"

Witness P: "The Serbs. Serbs because when they occupied the enclave they controlled the UN. They took over their vehicles and their checkpoints. So they occupied the enclave and we did not dare go to Potocari."

Judge: "How many people gathered -- men and boys -- in Susnjari?"

Witness P: "That number is between 13,000 and 15,000."

Fontana Hotel Meetings

Following the entry of Bosnian Serb forces into Srebrenica, three meetings were held at the Fontana Hotel in Bratunac. Two were held on the night of July 11 and one the morning of July 12.

At the first meeting, Bosnian Serb army Commander Ratko Mladic and other military officials invited UNPROFOR Colonel Thom Karremans, the commander of the Dutch battalion, to attend. He told Mladic there were about 10,000 women and children in Potocari and asked for a guarantee they would be allowed to leave the area.

Mladic asked to speak with a Bosnian Army representative. At that time, the Bosniaks' 28th Division along with the people in Srebrenica had already gathered to move toward Tuzla.

'Serbian Srebrenica'

Radovan Karadzic, the leader of the unrecognized Republika Srpska, issued an order on July 11 stating that "after the establishment of the authorities of the Republika Srpska in the area of the municipality of Srpska Srebrenica, a Serbian Srebrenica public security station will be established." It added that all people who fought against the Bosnian Serb army should be treated as "prisoners of war."

During the hearing for Karadzic's case in the appeals chamber of the International Mechanism for Criminal Courts in March 2019, Karadzic's order was used as proof that there was intent to permanently remove people from the Srebrenica enclave.

“In concluding that Karadzic shared the common goal of eliminating Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica through forced removal and that he had significantly contributed to the implementation of that joint plan, the Trial Chamber took into account, inter alia, three orders relating to the situation in Srebrenica that Karadzic issued immediately after the fall of the enclave on 11 July 1995,” the verdict reads.

Srebrenica Falls

The second meeting at the Fontana Hotel was held later on July 11 and, in addition to representatives of the Dutch battalion, Bosnian representative Nesib Mandzic was present.

At the third meeting at the Fontana Hotel on July 12, Mladic ordered the evacuation of the refugees.

He also said that all men between the ages of 16 and 60 will be separated from the others in order to find "war criminals."

The representative of the Dutch troops, Bosniak representative Nesib Mandzic, and two unofficial representatives of Potocari refugees -- Camila Omanovic and Ibro Nuhanovic -- were at the meeting.

Mladic again made it clear that military surrender was a condition for the survival of Srebrenica's Muslims. He said he would "guarantee life" to all those who lay down their weapons and he reiterated that the decision was up to them: they can "survive or disappear."

"Srebrenica has fallen and the evacuation of refugees has begun," the Dutch battalion's July 12 report said.

The report also details talks between Dutch battalion Commander Thom Karremans and Bosnian Serb army Commander Ratko Mladic at the Fontana Hotel, noting that Bosnian Serb forces gave an ultimatum to Bosnian soldiers around the base to hand over their weapons.

But the report said "There are no armed [Bosniak] soldiers around the base."

Liquidate The Enemy

The Drina Corps command issued a notice stating that on the morning of July 12 the column of men that had begun walking from Srebrenica came across a minefield and were most likely near Cerska.

"Having in mind it is very important to arrest as many broken Muslim formations as possible or liquidate them if they offer resistance, it is also necessary to record all military-ready people who are being evacuated from the UNPROFOR base in Potocari.... With the obtained data, plan joint activities for the purpose of breaking up and liquidating the enemy formations that are trying to get out of the Srebrenica enclave toward Tuzla and Kladanj."

The order was signed by Major General Zdravko Tolimir, assistant commander for intelligence and security affairs of the Bosnian Serb general staff.

Separating The Men

Bosnian Serb forces began to separate the men from the other refugees in Potocari.

A witness from the Dutch battalion saw the men being taken to a zinc factory and then taken away by truck the same evening. When the refugees began boarding buses, Bosnian Serb soldiers systematically singled out men trying to board. These people were taken to a Potocari building known as the "white house."

Later, one of the witnesses during the The Hague trial of Bosnian Serb Deputy Commander Radislav Krstic said:

“A soldier jumped out of the left column and addressed my child. He told us to turn right and he told my son, 'Young man, you're going to the left.' I grabbed his arm.... And then I begged them, I begged them. 'Why are you taking him away?' He was born in 1981. But he repeated the order. And I held him so tight, but he grabbed him.... and he grabbed my son by the arm and dragged him to the left. And [my son] turned around and said: 'Mom, can you bring me this bag? Can you keep it, please?' That was the last time I heard his voice.”

From the afternoon of July 12 until July 13, 1995, the men detained in the "white house" were boarded onto separate buses and taken from Potocari to detention facilities in Bratunac. After taking them from Potocari they burned their personal belongings. It was then clear to the Dutch that the men were not being taken away to be "checked for war criminals."

Taking Women And Children

The Drina Corps Command issued an order to make all army buses and minibuses available and sent to Bratunac.

General Milenko Zivanovic signed an order stating that the vehicles must be brought to the football stadium in Bratunac.

In an intercepted conversation from July 12 between two unidentified men, there is talk of trucks, transportation contracts, and a lack of fuel. Additionally, there is evidence in The Hague tribunal's database of getting fuel for vehicles being an issue during that period.

At about noon, dozens of buses and trucks began arriving in Potocari to pick up women, children, and the elderly to take them to Kladanj near Tuzla. Most of the people didn’t know where they were going. One female refugee testified at The Hague:

"Nobody asked us anything.... They just brought in the buses," she said. "And they knew, because there was such chaos in Srebrenica, so they knew that if they brought those five buses, or any number of vehicles, people would just leave. Because before that they had spent such horrible nights.... We just wanted to go, to go, just not stay there. And we didn't even have any other option.... We were not asked anything.”

The buses stopped near the village of Tisca near Kladanj. Dutch soldiers managed to follow the first convoy but subsequent attempts failed when Bosnian Serb forces confiscated their cars, weapons, and other equipment. After UNPROFOR was unable to follow the buses at Tisca, the rest of the men who were in the buses were taken to Bratunac and were separated. The evacuation of the civilian population from Potocari was completed by the evening of July 13.

Begging For Access

Concerned about the large number of displaced persons from the Potocari "safe area," the lack of food and health care, and recalling the 1993 demilitarization agreement that the signatories did not abide by, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1004 on July 12.

In it, Bosnian Serb forces were asked to allow the UN and other international aid agencies access to Srebrenica.

'We Will Stop Them'

In an intercepted conversation between Bosnian Serb Major Dragan Obrenovic and an unknown general, it was said that a column of people 2 or 3 kilometers long was moving near the school in the village of Glodi.

Obrenovic: "Listen to those ambushes of mine that I set up there on the wide road and on the part by Glodanski brdo; they just called me two minutes ago, a large column of Turks, uninterrupted and long, 2 or 3 kilometers from the school in Glodi."

An unnamed general orders soldiers to "go and to drive up there as soon as possible."

Unknown Bosnian Serb general: "OK boss, no one can pass [here]."

Obrenovic: "We will stop them."

On that same day, many men from the column heading toward Tuzla were captured. Several thousand of them were taken to a field near the village of Sandici and to the football stadium in Nova Kasaba.

First Mass Killings

Hundreds of men from the column that tried to reach the security of Bosniak territory but were caught by Bosnian Serb forces were transported to various locations in the Cerska Valley around the Jadar River and then to the Kravica warehouse where they were executed.

Between 1,000 and 1,500 men from the column had fled through the woods but were captured in a field near Sandici. They were taken by bus or forced to walk to the warehouse on the afternoon of July 13.

When the warehouse was filled with men, Bosnian Serb soldiers threw hand grenades inside and then shot at the people there.

About 4,000 other prisoners were transferred to Bratunac. Dozens of prisoners were reported killed in the morning.

'Just Cleaning Up?'

An intercepted conversation was also recorded between a man named Pajo and another named Lukic in which they spoke of a "big column [of men]." When Lukic asked what was happening with "that big column," Pajo answered that it was "over" and that everything was "processed and enclosed."

On the same day, in another recorded conversation, two unidentified people spoke about "their" soldiers who fled into the woods.

X: "Down around Kasaba and Konjevic Polje, it's a hassle now to get [them] all out."

Y: "Are they active or is it just cleaning up?"

X: "Well there’s a little bit of everything. There are those who mostly surrender but there are also those who still resist."

Dying Very Fast

Bosnian Serb forces transfered thousands of prisoners from Bratunac in a convoy of 30 buses to a school in Grbavci near Orahovac. Survivors estimated there were a 1,000 people there. Three survived the executions.

Later in the afternoon, another large group of some 1,500-2,000 prisoners from Bratunac was taken north to a school in Petkovci. On the night of July 14 the men were taken by a truck to a rocky area near the Petkovci dam. Two survived.

Witness O, who turned 17 in July 1995 and survived the shooting, testified in the case against Bosnian Serb army Deputy Commander Radislav Krstic.

“I saw rows of people who had been killed," he said. "It looked like they had been lined up one row after the other. I couldn't see the end of it but I could somehow sense it, although it was dark. So when I reached my spot, at that point we were watching those dead people. You could tell that those were dead people. There were several Serb soldiers there. I don't know how many, five or 10, but they were standing behind us. But it all happened very quickly, in a matter of seconds. And then I thought that I would die very fast, that I would not suffer. And I just thought that my mother would never know where I had ended up. This is what I was thinking as I was getting out of the truck. And when we reached the spot somebody said, "lie down." And when we started to fall down to the front, [when] they were behind us, the shooting started. I fell down and I don't know what happened. I wasn't thinking. It wasn't my idea to fall down first and to survive like this, I just thought it was the end.... All I know is that while I was lying down I felt pain on the right side of my chest. I felt pain on the right side, but I didn't know where I had been wounded and I felt pain in my right arm. And I suffered. But I kept lying like that on my stomach with my head turned to the right.”

Lined Up...And Shot

At least 1,200 prisoners were transported by bus to the school in the village of Pilica, north of Zvornik, on July 14. As in other detention facilities, there was no food or water there and several men died from heat and dehydration in the school gym.

People were kept at the school in Pilica for two nights.

On July 16, people were called out of the school and they boarded buses with their hands tied behind their backs. They were then taken to the Branjevo military farm, where they were lined up in groups of 10 and shot. Between 1,000 and 1,200 people were killed at that execution site on that day. At least 500 men were detained and executed at the House of Culture in the center of the village of Pilica. No one survived the massacre.

Drazen Erdemovic, from the Bosnian Serbs' 10th sabotage squad, pleaded guilty before The Hague tribunal in 1996 and testified about the shooting of detainees at Pilica.

"Buses started arriving," he said. "They took people out in groups of 10 to the meadow. We shot at people. I don't know exactly, to be honest, I couldn't even follow, that was so much for me.... I don't know. I was sick, my head hurt. I pulled [back] as hard as I could, just not to take part in it. I wanted to save one man; however, they did not allow that either. The man said he was helping the Serbs to move from Srebrenica to the...Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. I had at least that, the fact that he was helping. And...that didn't help [him] either, because they said...allegedly, Brano said he didn't want any witnesses to the crime [so they killed him]. I was silent."

Erdemovic was the first person to plead guilty at the tribunal and later testified in other proceedings at the court, providing detailed evidence of the crimes committed. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

3,500 ‘Packages’

After the mass executions began, there was an intercepted conversation recorded between the Bosnian Serbs' Colonel Ljubisa Beara and Major General Radislav Krstic in which Beara asked for additional troops.

"I understand, but understand me, too, if it had been respected on the 13th we wouldn't have argued about it on the 15th now," said Beara. "Well I don't know what to do, I’m telling you this most seriously with another 3,500 packages that I have to distribute. And I have no solution.”

"Packages" was code for people, for men captured in Srebrenica and columns that tried to escape to Tuzla. In a recorded conversation on July 14 it was said that the officer on duty from the Zvornik Brigade told Beara, the chief of security of the general staff, that he had "huge problems. Well, with the people, ah, [I mean] with the packages."

The Opel

Among the evidence that Bosnian Serb forces knew about the mass executions of the men from Srebrenica was the presence of an Opel car that was assigned to the Zvornik Brigade's command on July 13, 1995, and was part of the Drina Corps.

Records show the car was in Orahovac, where a mass execution took place on July 14, and in Bratunac, where Bosniaks had been detained. On July 14, the vehicle drove to Orahovac and Rocevic twice. On July 15, the vehicle was in Kozluk (where many killings were carried out from July 15 to July 17), in Kula (where men were detained at a school on July 14-15), in Pilica (where a mass execution was carried out on July 16), and Rocevic. On July 16, the vehicle drove to Kozluk, Pilica, Rocevic, and Kravica.

On July 16, some 1,000-1,200 men were executed at the Branjevo military farm in the village of Pilica.

'Executed On The Spot'

Jean Rene Ruez testified at several trials for Srebrenica crimes at The Hague tribunal. As chief investigator of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Ruez had first interviewed survivors of the massacre shortly after the fall of Srebrenica.

"As for the men who were in Potocari, they were executed. On the way most of the men managed to board the buses that were separated from the convoy at various moments, in Tisca, and from there they were also taken away and executed. Those who escaped through the forest either had to surrender or were captured. In a large number of situations, people who surrendered were executed on the spot. Most of them were [brought together into groups] on July 12 and 13, 1995. Gathering centers [were set up] in Nova Kasaba, Cerska, and Sandici, as well as elsewhere, and executions also took place there. Some were massive. The prisoners, for example, were taken from Sandici to Kravica, to a hangar in Kravica, and all were executed in that hangar. Other executions took place at the intersection of Konjevic and Nova Kasaba, where people were killed in groups of 10. And some groups were also taken to Cerska and executed there."

Mass Graves Seen

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright showed the Security Council satellite images believed to represent mass graves. This lead to UNSC Resolution 1010, which called on Bosnian Serbs to allow the UN and the International Commission of the Red Cross to enter Srebrenica.

See the documents here and here.

The exhumation of the mass graves began in July 1996.

To date, 94 mass graves have been exhumed in Srebrenica and the surrounding municipalities while the remains of at least 6,955 victims have been positively identified.

Hiding Bodies

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia found that forensic evidence that had been presented showed Bosnian Serb forces had excavated many of the primary mass graves and reburied bodies over several months in September and October 1995 in more remote locations.

Documents presented at the trials by Jean-Rene Ruez, the lead investigator for the The Hague prosecution team from 1995 to 2001, showed that sites with remains of genocide victims had been excavated.

Momir Nikolic, an intelligence and security officer for the Bosnian Serbs' Bratunac brigade, also testified about the transfer of the bodies of the Srebrenica residents who had been killed. He later pleaded guilty at The Hague tribunal and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

"Between September and October 1995 the Bratunac brigade, working with civilian authorities, excavated a mass grave in Glogova and other mass graves with Muslim victims of the killing operation and moved the bodies to individual mass graves in the wider Srebrenica area. In September 1995, I was contacted by Lieutenant Colonel Popovic, the security chief of the Drina Corps, and told to move the bodies of Muslims from Glogova.

"I coordinated the action of exhuming and reburying the bodies of Muslims in the period from mid-September to October 1995. This was done in cooperation with the military police of the Bratunac brigade, the civilian police, and parts of the 5th engineering battalion of the Drina Corps. At a meeting of the Bratunac brigade command in October 1995, I reported to the assembled officers from the command...that we had been given the task of carrying out an operation for the [Bosnian Serb] main staff to move the bodies of Muslims."

1st Genocide Verdict

Bosnian Serb General Radislav Krstic was sentenced to 46 years in prison for genocide on August 2 at The Hague tribunal. The sentence was later reduced to 35 years. This was the first genocide ruling

When atrocities were taking place in July 1995, Krstic was the first chief of staff and then took over as commander of the Bosnian Serbs' Drina Corps. All crimes committed after the capture of Srebrenica were committed under the command of the Drina Corps.

At his sentencing, Judge Almiro Rodrigues said: "It is not just a matter of committing murders for political, racial, or religious reasons, which in themselves constitute a crime of persecution. It is not just about the extermination of able-bodied Bosnian-Muslim men. It is a deliberate decision to kill these men, made with full awareness of the consequences that these killings will inevitably have for that group as a whole. The decision to kill able-bodied men in Srebrenica decided to prevent the survival of the Bosnian Muslim population of Srebrenica. In other words, from ethnic cleansing to genocide. The [court] chamber is therefore convinced that the crime of genocide was committed in Srebrenica beyond a reasonable doubt."

Srpska On Srebrenica

The Commission for the Investigation of Events in and around Srebrenica, which was formed by the government of the Bosnian entity Republika Srpska in 2003, issued a report in June 2004 on the events in Srebrenica from July 10 to 19, 1995.

This report also confirms the fact that there were up to 25,000 refugees in Potocari on the evening of July 11. The commission also determined the official number of people killed in the genocide at 8,742.

The Republika Srpska government adopted the report on June 11, 2004, and 11 days later Republika Srpska President Dragan Cavic said in an address:

"Instead of seeking a balance in the crimes committed, it is time for all of us in Bosnia-Herzegovina to turn to seeking a balance of justice for the perpetrators of crimes. The truth, no matter how difficult, must be established because if we do not establish it ourselves, the truth will be revealed [another way]."

In August 2018, the Republika Srpska's National Assembly annulled the report and decided to form a new commission.

The Scorpions

During the cross-examination of a witness in the trial of former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in June 2005, a video was shown in court with a Serb paramilitary unit called the Scorpions near Trnovo -- close to Sarajevo -- executing six male Bosniaks who were captured after the fall of Srebrenica in 1995, about 200 kilometers away.

Genocide Rulings

Former Bosnian Serb army officers Lieutenant Colonel Vujadin Popovic and Colonel Ljubisa Beara were sentenced to life in prison for participating in genocide against Bosniaks in Srebrenica in June 2010. Five other members of the Bosnian Serb army and police also received prison sentences for Srebrenica crimes. Zdravko Tolimir, assistant commander for intelligence and security affairs in the Bosnian Serb army's general staff, was also sentenced to life in prison for genocide.

Additionally, numerous trials for genocide and other crimes committed in the Srebrenica area were conducted.

According to the Srebrenica Memorial Center, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the Courts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and courts in Serbia have sentenced some 50 people to more than 700 years in prison for crimes committed in Srebrenica.

Russia Rejects Genocide

Russia vetoed a UN Security Council resolution that would have condemned the Srebrenica massacre as genocide on July 8, 2015. Russian Ambassador to the UN Vitaly Churkin said the resolution was "anti-Serb" and took the action after receiving requests from officials from Serbia and Republika Srpska.

The next day, the European Parliament and the U.S. Congress adopted resolutions restating that the events in Srebrenica had been a genocide.

Mladic Gets Life

Bosnian Serb army Commander Ratko Mladic was sentenced to life in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity on November 22, 2017. The Hague tribunal also found him guilty of persecution, extermination, murder, deportation, forcible transfer, terrorism, unlawful attacks on civilians, and hostage-taking.

"The [court] Chamber found the accused intended to eliminate Bosnian Muslims from Srebrenica by killing men and boys and forcibly removing women, children, and some elderly men by committing genocide, persecution, extermination, murder and inhumane acts of forcible transfer," stated the verdict against Mladic. His sentence is still under appeal.

And Life For Karadzic

The Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, as the legal successor to The Hague tribunal, confirmed the sentence of Radovan Karadzic, former Bosnian Serb president and commander in chief of its army, of life in prison on March 20, 2019. He had been first found guilty in 2016.

Danish Judge Wagn Joensen said Karadzic was guilty of genocide, crimes against humanity, and violations of the laws and customs of war.

Dutch Guilt: 10%

The Dutch Supreme Court upheld a ruling limiting the responsibility of the UN's Dutch battalion, the "blue helmets," for the genocide at Srebrenica, to 350 people on July 19. The court ruled that the probability that the liquidated men could have survived had the soldiers protected them after the fall of Srebrenica was only 10 percent.

During the first verdict in 2014 and the appeal in 2017, the court put the responsibility for the Dutch batallion at 30 percent based on the estimated probability that the captive Bosniaks would have survived if they had been allowed to stay at the UN base.

No Genocide Denial Law

Srebrenica had a population of some 37,000 people in 1991 -- four years before the genocide -- but in the 2013 census only 13,409 people were registered.

Within several days in July 1995, more than 8,000 male Bosniaks were taken prisoner after the fall of Srebrenica and executed as more than 25,000 people were expelled from the town.

According to the International Commission on Missing Persons, 6,955 victims of the Srebrenica genocide have been identified, about 85 percent of the number of known victims.

Only a small portion of the massive number of crimes committed by Bosnian Serb forces in and around Srebrenica -- which includes rape and torture in addition to killing -- has been presented in this timeline.

Much more evidence exists in the verdicts presented by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and in the memories of survivors.

Twenty-five years later, Bosnia-Herzegovina has no law against genocide denial -- a phenomenon that is growing in the Balkan country even as families continue to search for the more than 1,000 genocide victims still missing.

"Those who plan and carry out genocide want to deprive humanity of the great and diverse wealth of its peoples, races, ethnic groups and religions. It is a crime against all of humanity and its consequences are felt not only by the group set aside for destruction, but by all of humanity."

It has been 25 years since the army of the self-declared Republika Srpska entity committed genocide against the Muslim population based in Srebrenica in July 1995. With more than 8,000 known victims of the massacres, the remains of 6,955 people have been identified.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has convicted 20 people of crimes in Srebrenica, seven of them for genocide. According to the Srebrenica Memorial Center, Bosnian courts convicted an additional 26 people, 13 of them for genocide.

So far, 94 mass graves have been found in the area around Srebrenica: primary, secondary, and sometimes tertiary, in which the Bosnian Serb soldiers buried Bosniaks after executing them.

Although the courts have handed down a lot of verdicts, many perpetrators of the genocide have not been brought to justice.

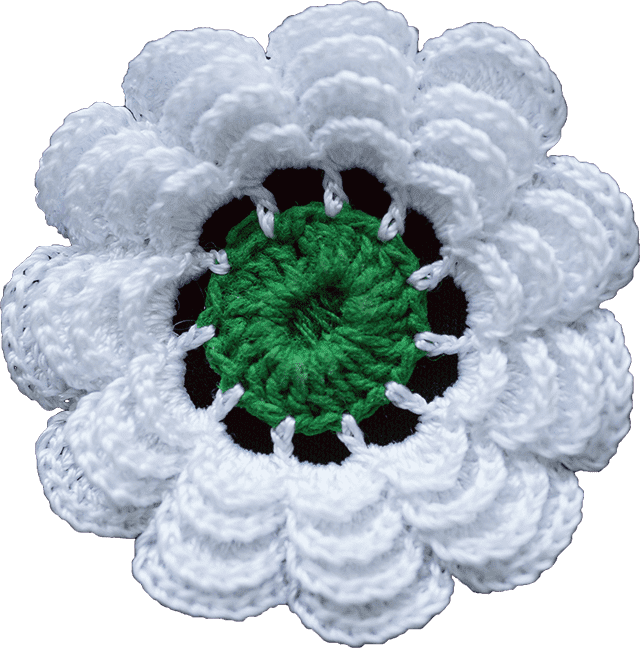

(The Srebrenica Flower is a symbol of remembrance for the genocide victims. White signifies innocence and green signifies hope, while the 11 petals represent July 11, 1995, the first day of the genocide.)

Written by Una Cilic

Edited by Pete Baumgartner

Design by RFE/RL’s Pangea Digital team