- June 25, 2018

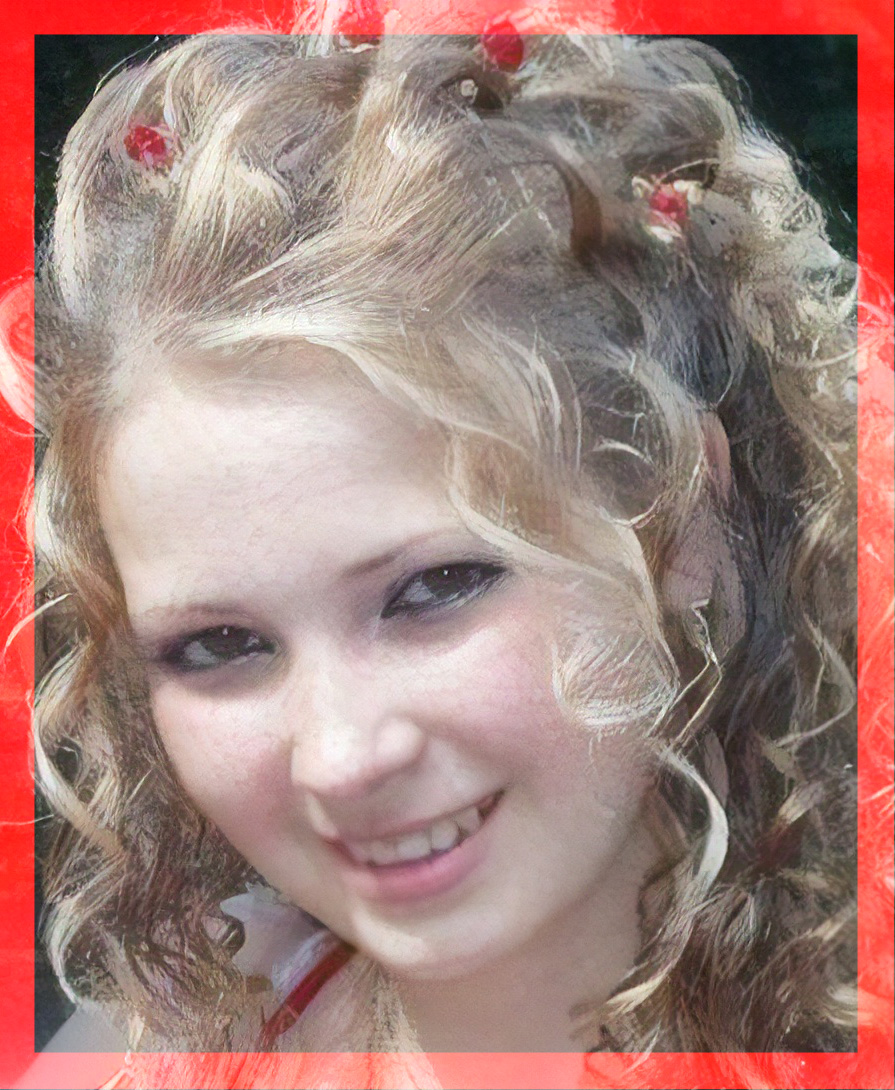

DEMYDIV, Ukraine – As darkness set in one Friday in late December, Iryna Nozdrovska, mindful of death threats and the concern that running late could cause her parents and her teenage daughter, made a quick phone call.

Nearing the end of her daily commute into the capital, the 38-year-old single mother and cherished daughter said she'd be in the village soon and her mother could start on dinner.

But dinnertime came and there was still no sign of Iryna.

Her family, convinced that their own neighbors posed the greatest threat to the crusading lawyer and tireless campaigner to keep her sister's killer behind bars, walked together to the bus stop. They watched as headlights pierced the cold darkness and buses disgorged commuters before rumbling off to even more remote villages than theirs.

Fearing a kidnapping, they called the police and waited a full two hours for officers to arrive.

"They didn't take us seriously," Iryna's 18-year-old daughter, Anastasia, says of the police response on that December 29 evening. "They accused us of planning a PR stunt."

The family enlisted neighbors to form a search party, struggling to maintain hope as the hours, then days, passed.

- June 25, 2018

Iryna

Many of those same friends and loved ones describe Iryna as a smart, spirited woman full of empathy.

Despite the family's meager resources and modest life in Demydiv, a quiet village about 40 kilometers upriver from the Ukrainian capital, Iryna became a talented pianist and earned a bachelor's degree from a musical college.

After graduating, now a single mother, Iryna recognized that her teaching salary at a music school couldn't support a family. That realization, and her sense of justice, prompted her to enroll in a master's program at the state-owned National Academy of Internal Affairs. Soon she earned a law degree that she hoped would provide the tools to pursue justice on a local level and to encourage all of Ukrainian society to more fully embrace the rule of law.

Iryna put her work on hold briefly to join the Euromaidan protests that broke out in late 2013, along with thousands of other Ukrainians on Kyiv's Independence Square to demand a westward orientation, greater democracy, and a more transparent government that would clean up corruption.

Afterward, she worked on cases related to alleged corruption within public procurement and, for a period, was an assistant to former journalist and anticorruption activist-turned-lawmaker Tetyana Chornovil. In one case, Iryna uncovered evidence that the director of a public school had appropriated hundreds of thousands of hryvnyas, the Ukrayinska Pravda news site reported.

Closer to home, Nozdrovska also waged her own battles against injustice.

Iryna's mother, Ekaterina Dunyak, tells the story of her daughter stepping up after a neighborhood fourth-grader's heavy-drinking parents couldn't, or wouldn't, provide the girl with a dress for a school function. Displaying her typical brashness, she says, Iryna gave the parents a tongue-lashing before finding the youngster shoes and a dress. She even tailored and adorned the dress herself.

"She dressed the girl, got her hair done, and drove her to the celebration," Ekaterina says, "She went to the teacher and paid for the girl to have her photo taken."

When a teenage neighbor was fatally struck by a speeding car and the victim's family couldn't afford a lawyer, Nozdrovska agreed to represent their interests in court. She managed to convince a judge to keep the driver behind bars.

To Iryna, the teenager's case had echoes of the tragic death of her own younger sister, Svitlana Sapatynska.

Svitlana

It was warm and clear when the 26-year-old Svitlana, a college graduate who worked for a subsidiary of the country's largest confectionary, set out for the office shortly after sunrise on September 15, 2015. She planned on taking the same route she did each day, down Sunshine St. toward the bus stop on the main highway.

But around 8:00 a.m., Dmytro Rossoshansky, a neighbor and the nephew of a powerful local judge, was driving his silver Daewoo Lanos while heavily intoxicated, Iryna would later prove in court. Rossoshansky's car struck Svitlana from behind as it careened toward the edge of the road, dragging her some 20 meters and killing her on the spot.

Iryna's two-year fight to see Rossoshansky behind bars garnered national attention and became a symbol of Ukraine's struggle against entrenched corruption. It would also set into motion the events leading to her own eventual disappearance.

Rossoshansky had a long record of substance abuse, hospital records obtained by Iryna and seen by RFE/RL show. He had been admitted for severe intoxication on at least three occasions prior to September 15, and neighbors recounted several instances in which he was publicly drunk and belligerent.

Earlier in 2015, Iryna's teenage daughter, Anastasia, had filmed Rossoshansky drinking from a vodka bottle at a neighborhood shop when, she claimed, he ordered his friends to "take care of her." One of the men, Anastasia recounted, "grabbed me by my hair and slammed my head into the hood of a car." She was hospitalized with a concussion, medical records show.

Before he plowed over Svitlana, Rossoshansky had also been arrested for driving under the influence of narcotics, as well as for car theft and robbery. He walked free from each incident and kept his driving license. (Svitlana and Iryna's parents claim he did so with the help of the uncle, although they cannot offer evidence.)

"If he [Rossoshansky] had been punished for all he had done, both of my daughters would still be alive," says Ekaterina Dunyak.

In an effort to interview Rossoshansky family members at their home on Sunshine St., RFE/RL was turned away by an armed police officer who said they had gone to stay with a relative in Kyiv.

Iryna fought tirelessly, even quitting her job to focus solely on her sister's case. She frequently skipped meals and sleep, the family says, her already petite frame growing even daintier.

"She would sit down right in this spot and work on her computer until 5 a.m.," her mother says, pointing to the family's worn-in sofa. "She swore to [Svitlana] when we buried her that she wouldn't sleep until she punished her murderer."

In court, Iryna had argued that the police, aware of the family connection between Rossoshansky and the uncle the Dunyaks claim was protecting him, waited eight hours before testing Rossoshansky's blood for drugs or alcohol. A judge subordinate to the uncle ordered Rossoshansky released on bail.

"When average people try to protect their rights in courts against someone who's powerful, they often end up with a completely unjust decision," says Mykhaylo Zhernakov, a former judge and director of a group pushing for judicial reform called Dejure. "That's how trust is lost in the courts."

One day, Iryna caught a break. She had filed an appeal to transfer the case to another district for a new trial based on a botched investigation and conflict of interest in the court of first instance. In June 2017, the second judge decided in the family's favor, finding Rossoshansky culpable in Svitlana's death and sentencing him to seven years in prison.

Ukrainian courts routinely free those accused of crimes pending trial or hand down short sentences upon conviction, according to Zhernakov. This is especially true in cases like Svitlana's, he says, when the perpetrator has powerful connections.

"These cases are rarely even registered with the investigative authorities," he adds.

'She Was Tortured'

By morning on New Year's Day of 2018, nearly three days after her disappearance and with her parents and daughter worried sick, Iryna still had not shown up. It was around noon as the family gathered the search party for another attempt to locate her, when a neighbor told Anastasia that the group could stop looking. Barely one kilometer from home, a passerby had spotted the naked body of a woman in the icy shallows of the Kozka River.

Iryna, who had embodied the struggle against corruption while fighting for justice for her late sister, had herself become the victim of a savage attack and another symbol of Ukraine's plight.

According to the results of an autopsy described to RFE/RL by someone who viewed both the report and her body but was not authorized to speak to journalists about it, Iryna had been stabbed at least a dozen times in her face and neck, including one blow that severed her carotid artery. The source said the wounds suggested the attack was "personal."

"She was tortured," Iryna's mother tells me tearfully at the family's cottage as two government-assigned security guards stand watch outside. Sitting alongside her husband, Serhiy, she cradles photographs of Iryna and Svitlana. "Nobody will ever call me 'Mother' again," she weeps.

Yuriy Rossoshansky was arrested and charged with Iryna's murder in January. The father of Dmytro Rossoshansky, he is currently awaiting trial. The families' homes are a mere 200 meters apart on Sunshine St.

The Rossoshanskys and their supporters were furious after the verdict in Svitlana's case and had openly threatened Iryna with violence, Anastasia and her grandparents say. Ekaterina Dunyak says threats were communicated directly on several occasions, while others came to them through the village grapevine.

One incident in late November stood out. Iryna's mother was walking home after visiting Svitlana's grave when she saw Yuriy Rossoshansky approaching. As he passed, she says, she muttered loudly enough for him to hear, "Murderer!" She says he glared at her and answered, "You'll bury your second daughter soon."

She told Iryna of the incident, but her daughter seemed to chalk it up to momentary anger. "Mom, he won't do it," Ekaterina Dunyak recalls her daughter saying. Trusting her, the family never asked for police protection.

Another threat would come a month later, the family says, during an appeal hearing on December 27 with both families and their supporters in the courtroom. The Rossoshanskys were hoping a judge would grant amnesty to their son -- based on two reported conditions, cirrhosis and hepatitis -- and release him in time to celebrate New Year's Day at home. They were shocked when the judge dismissed the request.

After the judge left the courtroom, Yuriy Rossoshansky exploded at Iryna, shouting, according to Iryna's father, "You'll get yours. This will end badly for you."

Deep Doubts

According to police and prosecutors, Yuriy Rossoshansky was drunk and hanging around the bus stop days later when Iryna got off the bus just minutes after telling her mother to start on dinner on that December evening. Iryna, they claim, provoked him by calling him a murderer and he reacted violently, killing her with 12 or 13 blows with a knife. Yuriy Rossoshansky is then said to have lifted her onto his shoulder, carried her to the shore of the Kozka River about a kilometer from the bus stop, and stripped her body naked and thrown it into the water. He then took her clothes home and burned them, according to investigators.

But the Dunyaks and their pro bono lawyer, Oleksandr Panchenko, don't buy that story, at least not completely. They say important questions about how exactly Iryna's killing unfolded remain unanswered, that the prosecution has refused to share all of its evidence with them, and that investigators ignored key evidence pointing to accomplices.

They believe Yuriy Rossoshansky had help from his wife, Olha, based on her refusal of a polygraph and phone records reportedly putting her in contact with her husband and son around the time Iryna was killed. They also allege that Olha Rossoshansky claimed the police offered her husband amnesty for their son in exchange for a confession.

Oleksiy Tsybenko, Yuriy Rossoshansky's lawyer, calls the Dunyaks' accusations as well as the authorities' account of events "fantastic."

The way Ekaterina and Serhiy Dunyak see it, the endemic judicial corruption that has plagued the country since Soviet times helped kill their daughters.

They are desperate for justice, which for them means not only a conviction in their case but reform of a corrupt judiciary that they say favors the powerful.

A national pollpdf conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI) in March shows Ukrainians largely agree. Asked whether the judiciary is politically independent, 82 percent of responders said "definitely no" or "somewhat no." Only 9 percent answered "definitely yes" or "somewhat yes."

Court reform has been a key demand of Ukraine's Western backers since President Petro Poroshenko came to power after the Euromaidan unrest and Russian invasion in 2014. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) halted a crucial disbursement of a $17.5 billion loan over Kyiv's failure to establish an independent anticorruption court -- a process that appears finally to be moving forward after key legislative votes this month.

The Dunyaks claim prosecutors and the judge presiding over Iryna's case want to tie it up quickly and that they are taking cues from Poroshenko, who publicly praised investigators in January for "a fast crime solution" and boasted in a March interview with the Financial Times of "a complete restart of the whole court system."

"That's a depiction of how the system at the highest level treats such [high profile] cases -- not putting all efforts toward fully solving them," Zhernakov, the former judge, says of Poroshenko's "fast crime solution" remark.

Zhernakov adds that those who go up against well-connected individuals are right to fear that justice won't be served by a court system that hasn't seen actual reform. "It's a fake process aimed only at making judges more beholden to the government," he says of the way judicial business has been run in Ukraine.

'I'll Fight Like My Mother'

The Dunyaks, frail in their old age, bear the calluses of village life and the sadness of having buried two daughters. They speak barely above a whisper except when they become angry at those they blame for taking them away. And they cry often.

When RFE/RL visits, they weep in part over the fact that Iryna's and Svitlana's cases have disappeared from newspaper and TV headlines. They fear nobody cares anymore.

"They were good girls. Now they're gone and I'm thinking maybe it was my fault, bringing them up like this. Maybe if they hadn't been so honest, they would still be alive."

Days later, at a small demonstration with fewer than a dozen activists in front of the Kyiv Regional Prosecutor's Office, Ekaterina Dunyak falls to her knees and sobs while pleading through a megaphone for authorities not to grant Dmytro Rossoshansky that amnesty and release him. Two TV journalists come and leave again within minutes.

Aside from attending the ongoing murder trial for Iryna, the Dunyaks must also be at continuing hearings on Svitlana's case to argue for keeping her killer behind bars for the duration of his sentence.

All the while, they don't feel safe at home in Demydiv, where neighbors remain divided over the cases. Serhiy Dunyak says nobody in the village speaks to anyone anymore, and if they do then it is often to "justify" the actions of the Rossoshansky family. They "pour dirt on us," he says.

Ihor Onishchenko, who lives directly across the street from the Dunyaks, acknowledges being friends with the Rossoshanskys and having disliked Iryna. She accused his family of being "alcoholics," he says, adding that he was brought in by investigators to undergo three polygraphs since her death.

"They thought I had something to do with it," he says.

Asked directly whether he did, he shrugs, flicks on a blow torch, and goes back to repairing his gate.

Ekaterina Dunyak meanwhile says her family lives in perpetual agony. She spends much of her time now planning her life around those court dates and trips to the cemetery to visit the graves of her daughters. In her darkest moments, she says she ponders whether she is partly to blame for their deaths.

"They were good girls. Now they're gone and I'm thinking maybe it was my fault, bringing them up like this," she says. "Maybe if they hadn't been so honest, they would still be alive."

Anastasia, who these days is trailed everywhere by a government-appointed bodyguard, worries about her grandmother's weak heart and the family's finances. Instead of studying this summer, she is getting a job to replace her mother as the breadwinner to help supplement the Dunyaks' pensions, which are little more than $100 a month, and pay for bills.

But inspired by her mother, Anastasia also plans eventually to complete her law studies at a Kyiv university.

"I've dreamed of becoming a lawyer, protecting human rights, helping people, and defending the interests of those who cannot do it themselves," she says. "I'll fight like my mother."

Edited by Andy Heil, with artwork by Wojtek Grojec.